Geez @herpetologyguy, what a cheery way to start off the morning. It's a nice sunny day, the kids are off to the first day of school and you decide it's the perfect time to talk about death.

Zoos and aquariums are advertised as places where you can watch animals live out their natural lives as best as they possibly can in captivity. Thanks to staff and keepers, the animals play, sleep, reproduce and behave as they would in the wild, and are provided with enrichment activities to engage in natural behaviors, such as hunting. They are critical institutions that connect people to nature, and allow us to learn about the natural world first hand. However, when watching the circle of life play out before you, it means that at some point you will see the tragic end of a life. No matter the care provided or the knowledge of the attending staff, death is an inevitable (and important) part of being a zookeeper.

Why am I writing about such a sore and depressing subject? Well, as much as I dislike talking or thinking about it, the fact remains that this is a fairly important aspect of animal care, but there actually isn't much information out there about zoo/aquarium animal deaths. We all know it happens, but it's not something that is often discussed, and I believe that leads to a lot of the misinformation surrounding these institutions and their level of care. How do animals in zoos/aquariums die? What happens after they die? What steps are taken to improve care for the remaining animals? We live in a time where these facilities fall under increasing public scrutiny (as a keeper, I believe that this is a good thing overall), and a lot of attention, both positive and negative, is turned towards zoos in the wake of an animal death. This will not be a particularly fun article to read, but I urge you to continue because understanding how we deal with death is, I think, incredibly important.

How do animals die:

The biggest killer of zoo/aquarium animals is old age and age-related health complications. Thanks to new information and technologies, animals in zoos are living far longer and more comfortably than they did even just a few decades ago. With top veterinarians and staff on hand, many animals are even living years past their natural life spans. Zoos provide a refuge from predators, diseases and lethal abiotic factors (drought, floods, etc), which means that as animals age, there isn't anything that could pick off or kill older or weaker animals. But no matter how long they hold on, at some point, they will still pass away. Our facility has been around for over 50 years; because we house species that have life spans as short as 1-4 years, death from old age is something we have to deal with fairly routinely, but fortunately doesn't reflect negative care (in fact, sometimes it shows a higher level of care!).

The Virginia Opossum generally lives about 4 years in the wild, however we have 2 that are approaching their 7th birthdays!

Next is death as a result of complications from the wild (or in some cases, previous captivity). Contrary to popular belief, most zoos do not go out and capture healthy animals in the wild and put them into captivity. The animals in zoos and aquariums are typically those that were injured or orphaned in the wild and are unable to survive on their own, part of a species survival conservation initiative, or were surrendered to the zoo as a pet or confiscated from an owner keeping them illegally. At our facility, we do not keep any animals that can be released into the wild; the majority of our animals are those that were once pets or were born in captivity, and legally cannot be surrendered. So how does this contribute to their death? The animals turned into our facility are generally not in perfect shape. Wild animals are brought in with injuries that may directly impact their longevity. Being a wild animal, they could have been exposed to diseases and more than likely carry some form of parasite. Even if we heal them up and keep them to provide care, all these conditions may mean a shorter lifespan. The captive animals that are turned in are generally pets that people no longer want or have found themselves unable to care for (always do your research before buying or adopting a pet!). In our herpetology department, we get a lot of animals with vitamin deficiencies, metabolic bone disorders, obesity or emaciation. We are almost always successful in restoring them to good health, but these complications may rear up in their later years and contribute to a shorter lifespan.

This is an extreme case of metabolic bone disease likely resulting from UV or nutritional deficiencies. Even with proper care, it will never go away.

Zoo accidents are incredibly rare (especially among reputable, accredited zoos) but they do unfortunately happen. One of the most common forms is death by ingestion; guests drop something into an exhibit, sometimes accidentally (like a phone or a hat) and sometimes on purpose (SO MANY COINS), and the animal consumes it after mistaking it for food. Depending on the item, this can cause perforation in the digestive tract, poisoning and lethal impaction...and it can kill before symptoms are observable. Rarer accidents may directly involve a guest and zoo staff have to put down an animal out of public safety concerns. These events generally gather international media attention, such as the shooting of Harambe the gorilla after a child fell into the exhibit last year. Following accidents like these, zoos typically make massive changes and upgrades to infrastructure and safety practices to eliminate any chance of a repeat occurrence.

If an animal's condition deteriorates too severely we may be forced to euthanize. This is typically only done with elderly animals or those turned in with the most severe injuries that cannot possibly be saved. In these instances, the animal is examined by our keeper staff, the resident vet or technician, and often times outside vet specialists on contract. X-rays and ultrasounds are taken to observe internal damage and the veterinary teams tries to assess the likelihood of recovery. However, when it comes to euthanasia, the biggest factor we take into account is quality of life; even if an animal could recover with a life of surgeries and extra care, it may be at the cost of the animal living comfortably. In these instances we may choose to euthanize an animal to spare it a life we deem to be poor quality (these are 100% the hardest deaths we have to deal with, but fortunately euthanasia is pretty uncommon for us).

Vet facilities in zoos and aquariums generally house the best tech, equipment and staff found anywhere!

What do we do with an animal that we believe may be about to die?

I begin every morning with a check in of all exhibits and holding areas, checking water levels, UV and temperature outputs, cleaning viewing glass and, most importantly, assessing animal health and welfare. During my rounds, if I see any animal that appears to be behaving out of the ordinary (even if it seems okay but just a little off), I immediately pull it from the exhibit and set it up behind the scenes. This allows them a chance to calm down in a non-stressful environment and most animals perk back up quite quickly. Every now and then, I pick up someone who appears to be at deaths door, who may only have days or even hours left. These animals are immediately taken to the resident vet for an assessment. If it is a younger animal generally known to be in good health, perhaps we can save it (maybe it ate something it shouldn't have or got into a scuffle with another animal), but if it's an older animal, our choices may be limited. Animals that appear in pain as they slip away are euthanized to spare their suffering; others may be given some medication to calm them and are allowed to pass on their own in a comfortable, stress-free location. It's one of the worst parts of being a keeper, but allowing animals to pass away peacefully in a safe place away from the eyes of guests gives me some comfort knowing we are making the passing as easy as we can.

Here are some pretty flowers because this is a rough subject and there is no happy picture that could accompany that paragraph.

What happens to the animal after it dies?

When an animal dies, a death weight is immediately recorded, and the animal is brought to our onsite veterinarian. With the help of keeper staff, the vet will perform an autopsy on the animal, regardless of whether or not the cause of death is known to us; the autopsy is performed on just about any animal, from our larger herbivores to our tiniest lizards and frogs. If the cause of death is unknown, it is up to the vet to determine exactly what killed the animal, and determine if there is a risk to remaining animals or other species. They also look at every single organ and record their appearance and feeling, whether they are pale, darkened, enlarged, have growths, or bear any other abnormalities that could indicate a health concern (lethal or nonlethal). Small tissue samples are taken from each organ and sent to an offsite laboratory that will test them for any number of diseases or conditions. Even if these samples bear signs of a problem, it may not be what caused the fatality, and could be a health concern among the remaining animals; the vet may decide to initiate a preventative treatment to be safe. It's a complicated process, but it allows us take the death of an animal and use it to the advantage of our remaining animals, improving their quality of life.

What happens to the exhibit after the animal dies?

The exhibit is immediately shut down in the wake of an animal death. If multiple individuals were housed, everyone is pulled out for a period of observation and vet check ups (even if we know the cause of death, it's a good time for a wellness check). The exhibit undergoes a routine cleaning and sanitation that may take several days to complete (if a single animal was housed there and is being replaced by another, this process prevents cross-contamination). The animals will not be returned to their home until after laboratory results from the autopsy have returned. In some instances, the test may reveal that foreign bacteria or fungi are present in the exhibit and it may require more intense sanitation preparation (anyone who doubts the level of care by zookeepers has never seen someone trying to sanitize dirt). Though guests (and administrators) are often unhappy with an empty exhibit, the animals are not returned until we can confirm that there is no possible risk to their health. (Note that an empty exhibit doesn't necessarily mean something died, we also do routine cleanings.)

How do the facility and it's keepers respond to the death?

We are devastated. From day one, keepers are lectured about not treating animals are pets or trying to personify them the way most people do. But being a zookeeper is an incredibly emotional experience, and working with the animals day in and day out, you become incredibly attached to them. They may not be "pets", but when one dies, it's like the death of a family member; for some of us, we've known animals since they were born or hatched. Keepers mourn the deaths of animals in their own way; many will take time off to process the loss and try to return with a clearer head. Some get directly involved in autopsy procedures because they feel a need to know what happened. Behind the scenes of our facility, our keepers have a small hallway of tributes to animals we've lost; photos, feathers, harnesses and other small mementos of the animals that changed their lives. It's one of the worst experiences of being a keeper, but it's that connection to the animals that drives us. In fact, zoo keepers rank among the lowest paid full time staff in the nation, but the turn over rate is one of the lowest. Keepers are here because the animals, and their connection to them, keeps them here.

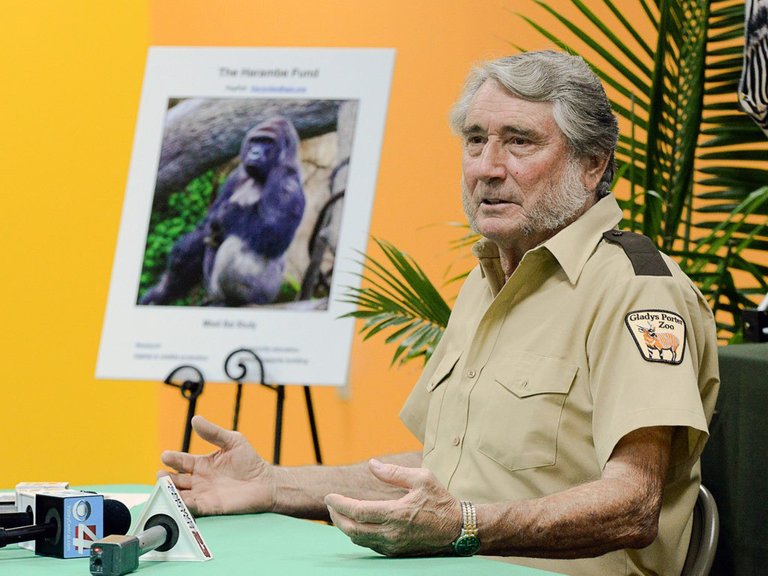

“We hand-raised him. I took him home at night with me. You know, you get up at midnight and change the diaper, just like you would a human baby. When I took this baby home, I was totally responsible. You become Mom. They look at you just like a human baby.” -Jerry Stones, talking about his experience raising Harambe as an infant Source

Most facilities are fairly open about deaths when dealing with the public. Though we try to keep medical details private, zoos and aquariums will typically make an announcement following an animal death; this is in part to be honest and stay ahead of negative press, but it's also for the benefit of our guests. We know how attached guests can be to the animals, and we want them to know what's happening, even in the worst scenarios. People will often visit the facility to mourn the animal in person, and others will even share their memories or photos of a deceased animal on social media. It's a sad time, but the death of an animal does strengthen our connection with the community that we rely on everyday.

Dealing with death is just about the worst experience for anyone, and zoos, aquariums and other facilities are deeply affected by the loss of an animal. To us they are family, and their unique personality and individuality is lost forever; we may be able to put a new animal on exhibit, but we can never really replace what was lost. But we can learn from death; we can improve the welfare of our animals by doing our due diligence to investigate and implement changes when an animal dies. This article was probably not a fun read, it sure as hell wasn't fun to write, but death is an important part of a keepers job. It's something that we will always have to death with, no matter how much zoos and aquariums change. What matters most is how we respond to those deaths, how we use them to improve, and how we move forward to provide the best care for our amazing animals.

Obligatory cute picture for making it to the end!

Image Links: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13

Thanks for that interesting insight on that aspect of zoos. It is a difficult subject, that gets complicated by the emotional aspects involved.

On one side there is the emotional attachment of the visitors and also the caretakers to the animals, on the other side the economical neccessaties that also zoos have to observe. This can result in situations, that - although totally reasonable in essence - are perceived as not appropriate by the public.

As a example: is it acceptable to use a dead Zebra (that died from a accident, not from disease) as food for Lions?

Many zoo visitors would striktly object to that idea, but in nature its a totally normal occurance. And for the zoo it saves a lot of money, not having to buy meat (which comes from formerly living animals too, btw) and not having to pay for the disposal of the dead body.

As a result, such things are done in zoos, they just dont like to talk about it.

Further more, zoos even breed certain animals only to use them as food, like mice, rats and various insects. I'm sure you - as a herpetologist - know that, and that it is inevitable for keeping certain snakes and lizzards.

Ok, the emotional attachment to rats and mice and grasshoppers is limited for most people, but in essence this is no different than the Zebra/Lion relation.

So, if we agree with the concept of having zoos at all (and I believe we will need them more and more, to preserve at least a few animals of certain species), we must learn to be realistic in such matters as well.

It's true. Everyone wants to see life as a happy Disney movie, but life is scary, ugly, beautiful, gross, etc. We try to show the happy, pretty, and cute side of life in zoos, but some animals just can't survive without the darker aspects of life (like my previous article about documentaries mentioned). I think zoos today are reaching a nice medium where we can appeal to the general public, while also ensuring the animals have access to all the necessities they require.

I guess zoos are in a difficult position. Their purpose is to educate people about animals, but people are more willing to pay for cuteness and emotional experiences. And most zoos depend on the money thats coming from the visitors, and that has led to - at least some - intolerable decisions. I just only mention the zoos holding Dolphins or even Orcas in captivity.

The only solution would be, if zoos are publicly funded and operate strictly scientificly. And if this is not showing enough cuteness and the people stay away, then so be it. The animals wont miss them, I assume.

I'm glad you bring up orcas especially. I'm doing a post about Sea World in the near future that I hope is enlightening and touches on the subject.

But I agree and this is a battle that I face everyday. Keepers are concerned with animal care practices and we often butt heads with the administration. They look at things from the guest experience point of view (because of money) and often ask us to do things that run counter to welfare practices in order to appease guests. It's understandable seeing as how management doesn't have the biology experience the keepers do, but it is aggravating just the same.

Yeah, I can well imagine that. Thare is a lot of weird stuff going on in that respect.

For example, lately it was announced, that a zoo in Germany is getting a Panda bear from China. It is strictly forbidden to export Pandas from China, though. So what the chinese government does, is running a "rent a Panda" business. The zoo has to pay close to a million dollars rent per year to the Chinese to get the Panda, and they have to return it if they dont pay.

It clearly shows that the zoo is expecting to make more than the million per year on additional ticket sales, based on the cuteness factor of the Panda for the visitors. This kind of deal is unacceptable in my opinion. Even if the Panda is having a good life in the zoo.

Orcas and Dolphins definately dont have good lifes in zoos, however. So I´ll be looking forward to your post covering that issue.

I'll have to look into the panda deal. On the surface, it is definitely questionable, but I do know that some zoos do "rent" or receive them on loan for breeding purposes. If the zoo already has a female for example, they may want a male for a short period to attempt to breed, hopefully helping the species survival plan, then they send the male back or onto another zoo. They loan or "rent" the pandas because it cuts down on poaching; you can't just buy a panda from China, but you can request to house one that technically belongs to the Chinese government (oh how I love when politics get into the animal business rolls eyes). But we actually do something similar with red wolves; our wolves belong to the federal government (they are extinct in the wild), but we house and care for them in their stead to protect the species.

This could be advantageous for the zoo, China, and the animals if carried out right. The zoo gets increased business because pandas are a crowd pleaser, the Chinese government is paid AND helping with breeding efforts of a native endangered species, and the pandas get an opportunity to mate and help replenish their numbers in a (hopefully) quality facility (although it usually has to be a top-notch place to be permitted for pandas!).

I'm sorry, I don't remember which zoo it was, but definately one of the big names. I also don't know if they had other Pandas already.

I do agree that it is in the interest of preserving the Panda species to run breeding programs. However, the enormous sum of 1 mio per year only for renting one makes it smell much like a money making scheme rather than a serious preservation effort. If zoos make the effort (and I´m sure thats not cheap as well) to provide a adequate habitat for the Pandas and participate in the breeding project, that should be enough to receive a Panda. At the end of the day, its the Chinese's fault that the Panda is endangered in the first place.

Its like when you are drowning, and someone comes to pull you out of the water, you say he has to pay you $100 first.

Beautiful work as always @herpetologyguy, you are seriously my number one source for herpetile news. :)

I always say that's the best kind of news! Thank you!

A quite exhaustive work. I hope it helps uninformed people who complaint against zoos. I think zoos and aquariums are not only a good place for take care of animals that cannot survive on the wild, but also for research and to raise awareness about nature preservation.

Have you ever worked in a zoo or circus with animals shows? Can I ask you your opinion about the care of animals that take part in that spectacles?

I haven't worked at a circus, no. And I don't have enough experience with circuses, the species generally associated with the circus or their training methods to have a particularly solid stance on them. I'm typically in support of the larger circuses (many of them do fall under Association of Zoos and Aquariums and USDA jurisdiction) depending on their level of care, but I have virtually no experience with that (and it's been years since I've been to one).

Facilities that do animal shows, I completely support (provided of course they provide good quality care, which they generally do). And I know that the big one people talk about is Sea World and their orcas (I'm actually planning to write a post about Sea World in the very near future because that is a bit more complicated). Animal shows are often labeled as demeaning or cruel, but in reality they can be incredibly beneficial. For example, I do "shows" with our alligator. From the guests perspective, I am showing off the various "tricks" that the gator can do, but there is a lot more than just performance here. For one, I am training the gator to respond to commands that will keep me safe when working in the exhibit. Staff and vets can also use these commands to make veterinary procedures easier and more comfortable for the animal (better to have the gator swim up and sit still for a shot that to have to wrestle it and hold it down...stressful for everyone to say the least). The show is also a chance for us to be closer to the animal, and we can do a good health assessment. If an animal is showing any signs of stress or a health concern, I can catch it during these shows. And most importantly, it is a form of enrichment; it engages the animal and gets them moving and thinking which is great for physical and psychological health. When carried out properly, animal shows are entertaining for guest, but more importantly a critical means for keepers to gauge animal welfare!

Very unique educational work today.

I might have missed it when reading, but are the animals cremated after their autopsies? Are they returned to the earth, etc? Some of this might be private to each zoo, but just wondering.

Thank you!

Yes, that's a good question, I almost included it but in the end edited it out. Like many vet offices, we have a company that comes out to pick up dead animals and the bodies are incinerated. It does sound very impersonal to say it like that, but it's the best means for ensuring that there is no risk of disease spreading (part of the reason our keeper have created their little memorial is because the post-death process is rather unceremonious). The Association of Zoos and Aquariums and USDA has very strict regulations when it comes to dealing with animals that have passed.

Makes perfect sense. Thanks for your prompt clarification. Looking fwd to the next post.

We shall require a substantially new manner of thinking if mankind is to survive.

- Albert Einstein

This is the first piece of yours I've read & you handled a hard topic beautifully.

I have to admit that like other readers, I was curious about the remains. My first assumption was that they were butchered & fed to the other animals, but I can see how it'd be way too hard on the staff since this is a being they loved.

Thanks for such an amazing read. I loved the pics, especially the giraffe. I'm jealous of the person that got to take baby Harambe home. Fostering & caring for animals has always been a dream of mine that hopefully will align with my living conditions some day.

If ever there's a volunteer program to comfort, snuggle & scritch animals like they have for prenatal babies, I am so there.

Thanks again for a truly great read, I'll try not to fangirl so much as I read other articles. That giraffe pic though! 😍

Thank you! It's a hard topic because, even setting emotion aside, it's easy to paint zoos in a negative light when talking about death. As hard as it is, death isn't necessarily a "bad" thing for zoos as long as it is handled carefully and with respect for the animal (which I personally believe it is these days). It's too easy for someone to see a zoo that has an animal die and get up in arms about it, so I'm glad this article could open that situation up for people to understand a little better!

Informative post. Really insightful. I love animals and this topic caught my attention.

Hi @herpetologyguy, I just stopped back to let you know your post was one of my favourite reads and I included it in my Steemit Ramble. You can read what I wrote about your post here.

If you’d like to nominate someone’s post just visit the Steemit Ramble Discord

Thanks! Glad you liked it!

nice informative post.thanks for sharing it with us.Upvote and a resteem from me friend.If possible please give a resteem to my post friend.Thanks.

https://steemit.com/steemit/@cutegirl/600-followers-thank-you-steemit-and-my-loving-friends

Very informative post really enjoyed it... upvoted!

This post received a 2% upvote from @randowhale thanks to @herpetologyguy! For more information, click here!

@herpetologyguy this article was absolutely fascinating. (talk about insta-follow!) Thanks so much for the education. Additionally, thank you for beating back the depression with the lovely flower after that emotional assault on my manly fortitude. More seriously, truly enjoyed this peak behind the scenes even if in involves the harsh realities you folks face. Keep up the great work both here on steemit and with those magnificent animals! Outstanding!!