History of Science: Antiquity to 1700

In this era, everybody knows what Is a science. But nobody knows the history of science. So I choose a topic to write "HISTORY OF SCIENCE".

The history of science is the study of the development of science and scientific knowledge, including both the natural and social sciences. (The history of the arts and humanities is termed history of scholarship.) Science is a body of empirical, theoretical, and practical knowledge about the natural world, produced by scientists who emphasize the observation, explanation, and prediction of real-world phenomena. Historiography of science, in contrast, studies the methods employed by historians of science.

The English word scientist is relatively recent—first coined by William Whewell in the 19th century. Previously, investigators of nature called themselves "natural philosophers". While empirical investigations of the natural world have been described since classical antiquity (for example by Thales and Aristotle), and scientific method has been employed since the Middle Ages (for example, by Ibn al-Haytham and Roger Bacon), modern science began to develop in the early modern period, and in particular in the scientific revolution of 16th- and 17th-century Europe. Traditionally, historians of science have defined science sufficiently broadly to include those earlier inquiries.

From the 18th century through the late 20th century, the history of science, especially of the physical and biological sciences, was often presented as a progressive accumulation of knowledge, in which true theories replaced false beliefs. Some more recent historical interpretations, such as those of Thomas Kuhn, tend to portray the history of science in terms of competing paradigms or conceptual systems in a wider matrix of intellectual, cultural, economic and political trends. These interpretations, however, have met with opposition for they also portray the history of science as an incoherent system of incommensurable paradigms, not leading to any scientific progress, but only to the illusion of progress.

History of science, the development of science over time.

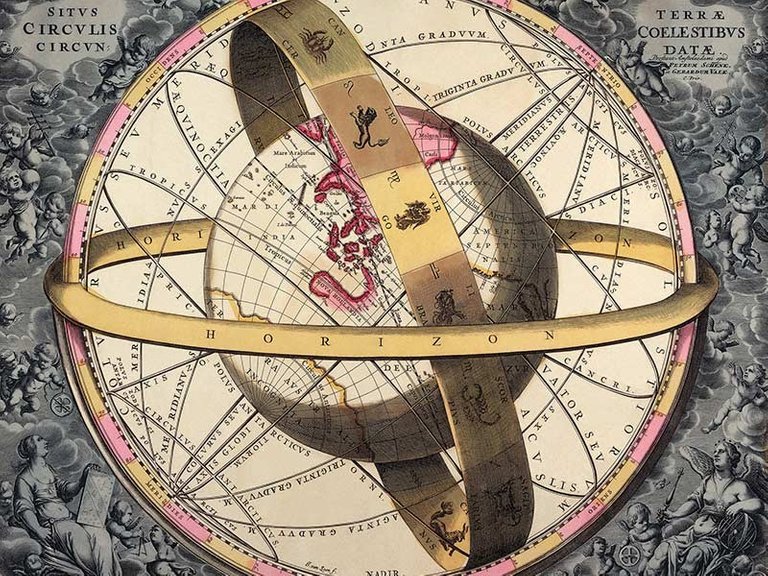

On the simplest level, science is knowledge of the world of nature. There are many regularities in nature that humankind has had to recognize for survival since the emergence of Homo sapiens as a species. The Sun and the Moon periodically repeat their movements. Some motions, like the daily “motion” of the Sun, are simple to observe, while others, like the annual “motion” of the Sun, are far more difficult. Both motions correlate with important terrestrial events. Day and night provide the basic rhythm of human existence. The seasons determine the migration of animals upon which humans have depended for millennia for survival. With the invention of agriculture, the seasons became even more crucial, for failure to recognize the proper time for planting could lead to starvation. Science defined simply as knowledge of natural processes is universal among humankind, and it has existed since the dawn of human existence.

The mere recognition of regularities does not exhaust the full meaning of science, however. In the first place, regularities may be simply constructs of the human mind. Humans leap to conclusions. The mind cannot tolerate chaos, so it constructs regularities even when none objectively exists. Thus, for example, one of the astronomical “laws” of the Middle Ages was that the appearance of comets presaged a great upheaval, as the Norman Conquest of Britain followed the comet of 1066. True regularities must be established by detached examination of data. Science, therefore, must employ a certain degree of scepticism to prevent premature generalization.

Science in Islam

The torch of ancient learning passed first to one of the invading groups that helped bring down the Eastern Empire. In the 7th century the Arabs, inspired by their new religion, burst out of the Arabian peninsula and laid the foundations of an Islamic empire that eventually rivalled that of ancient Rome. To the Arabs, ancient science was a precious treasure. The Qurʿān, the sacred book of Islam, particularly praised medicine as an art close to God. Astronomy and astrology were believed to be one way of glimpsing what God willed for humankind. Contact with Hindu mathematics and the requirements of astronomy stimulated the study of numbers and of geometry. The writings of the Hellenes were, therefore, eagerly sought and translated, and thus much of the science of antiquity passed into Islamic culture. Greek medicine, Greek astronomy and astrology, and Greek mathematics, together with the great philosophical works of Plato and, particularly, Aristotle, were assimilated in Islam by the end of the 9th century. Nor did the Arabs stop with assimilation. They criticized and they innovated. Islamic astronomy and astrology were aided by the construction of great astronomical observatories that provided accurate observations against which the Ptolemaic predictions could be checked. Numbers fascinated Islamic thinkers, and this fascination served as the motivation for the creation of algebra (from Arabic al-jabr) and the study of algebraic functions.

The Science History Institute collects and shares the stories of innovators and of discoveries that shape our lives. We preserve and interpret the history of chemistry, chemical engineering, and the life sciences.

From Science History To Science Today

“I worry that economic historians tend to sound like they have an axe to grind, and…I may sound like that as well,” says Garrick Hileman, a researcher and economic historian of alternative currencies. “But I think it is frustrating [for] economic historians to feel like their work is not getting the attention it deserves. Hileman isn’t alone. Many of the science historians interviewed for this article, while stressing that it was not a blanket statement, implied the need to argue for their discipline—and one method has been to demonstrate that the history of science is good for science itself.

Examples abound. In an Isis article titled “How Can History Of Science Matter To Historians,” the authors draw upon the first experimental research in tissue cultures by Ross Granville Harrison in the early 1900s, and how a graduate student discovered that Harrison temporarily worked next to the bacteriologists, who imparted essential information on maintaining aseptic conditions. And at the Field Museum in Chicago, photo historian Carl Fuldner worked with scientists to photograph and analyze the soot on the feathers of birds collected in the early 1900s, allowing researchers to trace the amount of black carbon in the air over time.

Horned Larks from The Field Museum’s collections, with grey birds from the turn of the century and cleaner birds from more recent years when there was less soot in the atmosphere. Credit: Carl Fuldner and Shane DuBay, The University of Chicago and The Field Museum

Thanks to the “cultural power of science,” says Appuhn, “there’s this way in which science becomes a black box, and we don’t get to see how it works.”

But when it comes to scientists, says Malone, they may be a bit more curious than the average person, but “they’re not in silos. Scientists aren’t special creatures independent of how humans operate. And what we try to do is humanize science and help people see that scientists are just like the rest of us…I think it’s really important that we help the public see that science is a process, that is being practised by humans, and it has foibles, like so many other human processes,” he says. “Nevertheless, it’s pretty powerful, what science is able to do.”

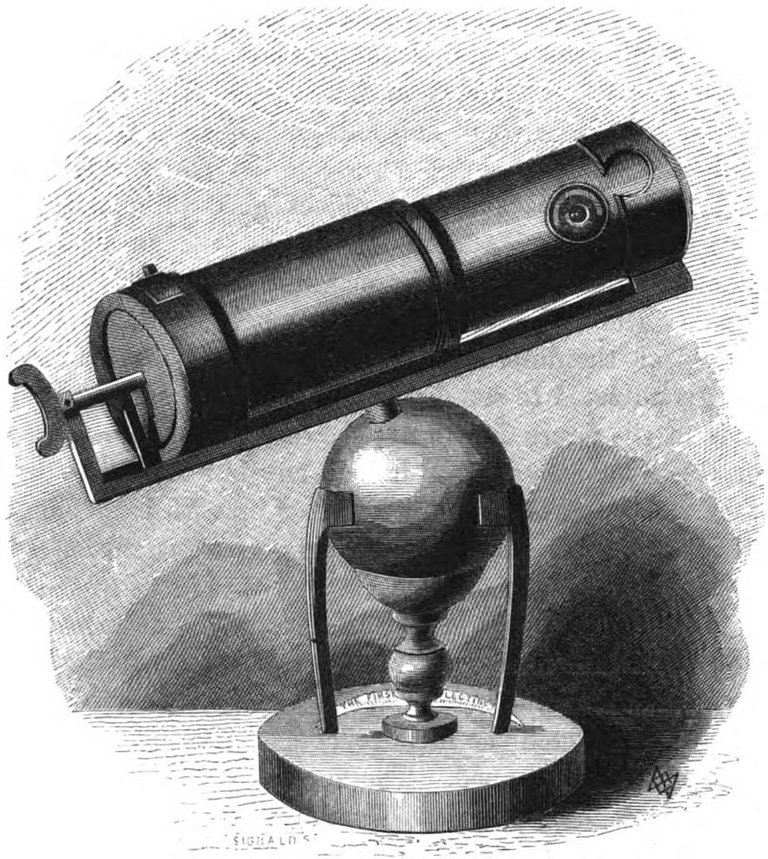

Newton's reflector, the first reflecting telescope.

I know that this is not the full history of science I looked into many websites and I do a lot more working in the history of science.

#I will make a second part of "History Of Science" if I get a good response on this Post.