This is Spirobranchus kraussii. This little marine worm was the basis of my year project I did for Stellenbosch University (situated in Cape Town).

In the beginning of 2017, I started my second year at the university and wanted to do research assistant work for a Lecturer or a Master student in Botany. But as you can see I did not assist in a Botany lab, but ended up in the Polycheatea Department (sea worms). I didn't mind, because any research experience is good.

Doctor Simon gave me a project that was handed to her by Professors in Australia and Netherlands doing research on the same species on their sides of the world, to make a comparison. I felt quite good about myself realising I'm helping out overseas Scientists who already have published quite a few papers.

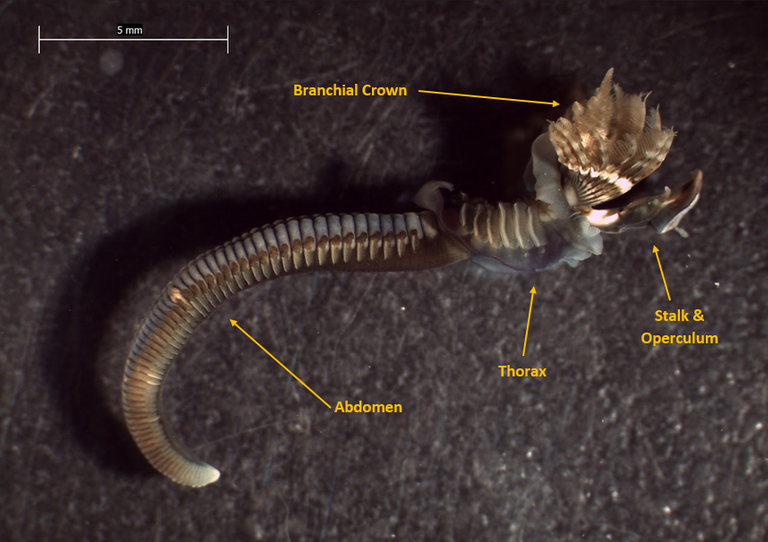

S. kraussii is a filter feeding worm, which lives almost its whole life in Calcite tubes, but they are not sessile. The worm sticks out its head at the opening of its tunnel and let the Radioles of the Branchial Crown collect anything edible (see picture below). The Operculum (the round disk) seal off the opening when the worm pulls into the tube. The Thorax is like a jacket, is has a Collar and a 'coat tail' to the end of the Thorax. It is a very fancy sea worm.

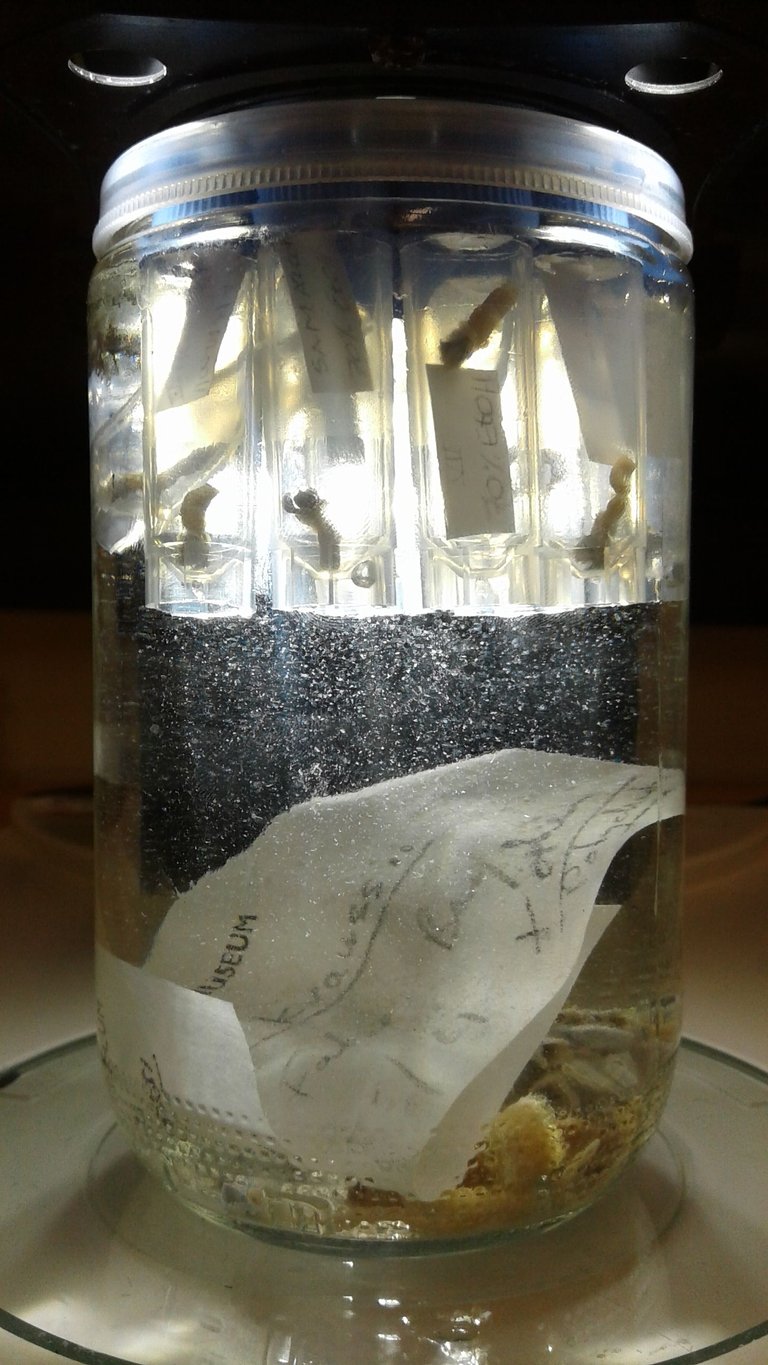

My task was to describe the species from Cape Town, specimen by specimen, according to a list of characteristics the Netherlands Professor emailed to me. The specimens came from different locations along the Cape Coast e.g Danger Point and Muizenburg. I even had to describe specimens from Cape Town Museum and specimens from the London Museum that was collected in Cape Town in 1840 (but these specimens were in very bad condition).

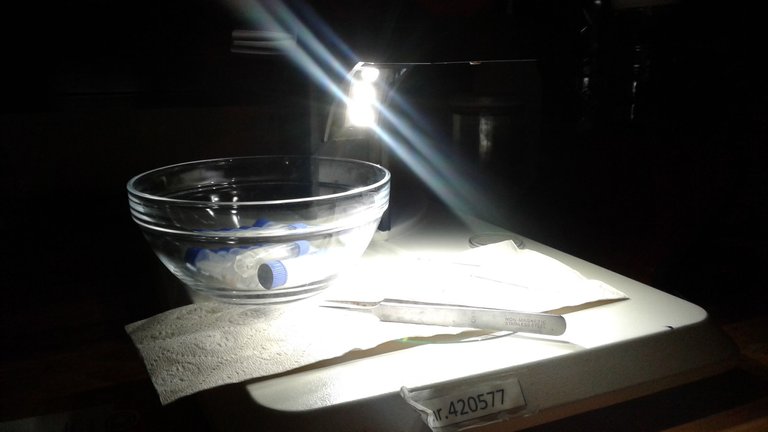

For fresh specimens, the Doctor and I went to the beach and searched for a colony of S. kraussii on the inter-tidal rocks. These worms build Calcite tunnels in which they live. When we finally find the heap of white 'worms', we collect only enough, not to much, and in the lab we processed them. First we place them in Sodium-hydroxide to make them 'sleepy' and with tongs we cut the Calcite tunnel, working with a light microscope to do this, to extract the worm on the inside. This part is very difficult, firstly because the worm is very small and can easily be cut in half when to much pressure is used. And secondly the calcite 'walls' is very hard. After the extraction, I placed them in Formalin and then in Ethanol so that I can then start describing them under the microscope.

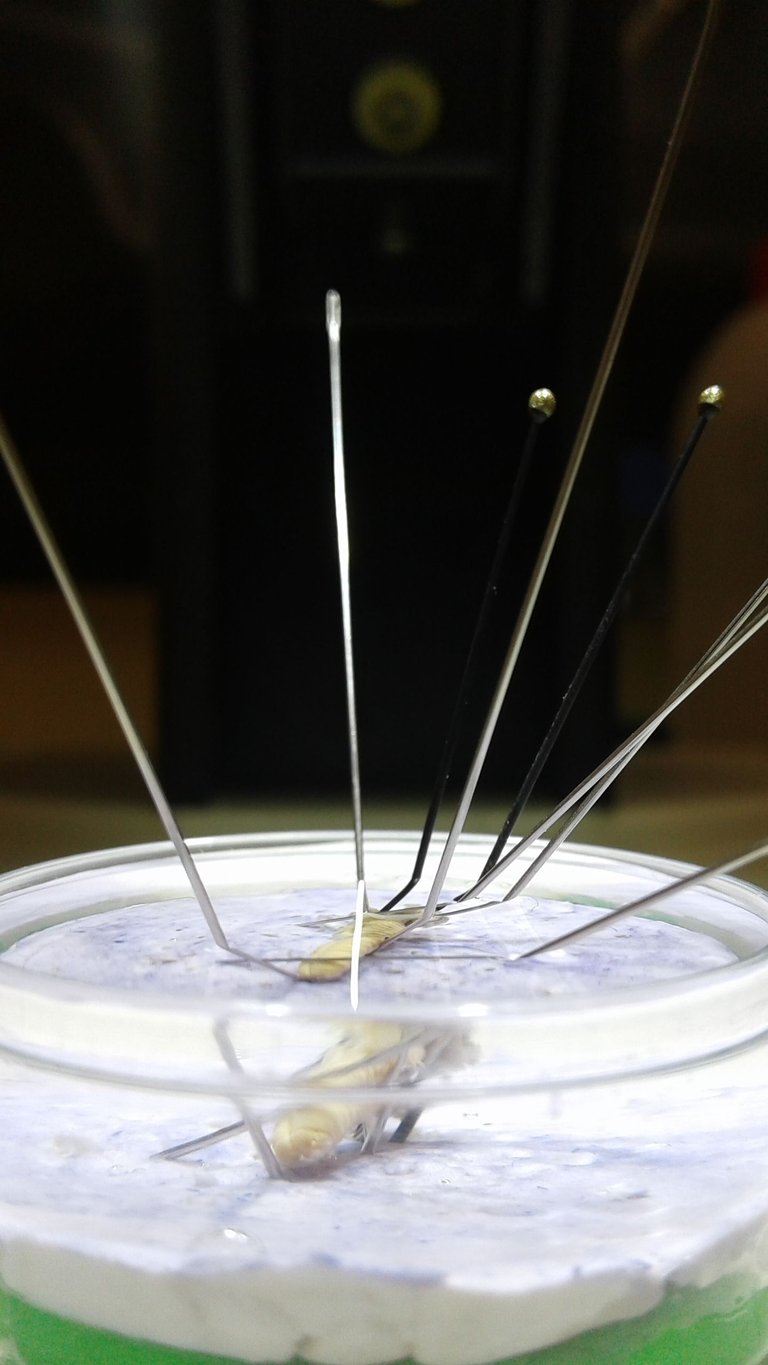

By using a Light Microscope, I looked at each specimen independently. I had to describe the colour patterns, count the segments and radioles on the Branchial Crown, measure the lengths, check for the presence or absence of specific features, etc. For some characteristics I had to pin them down with needles so that they don't move, without damaging them.

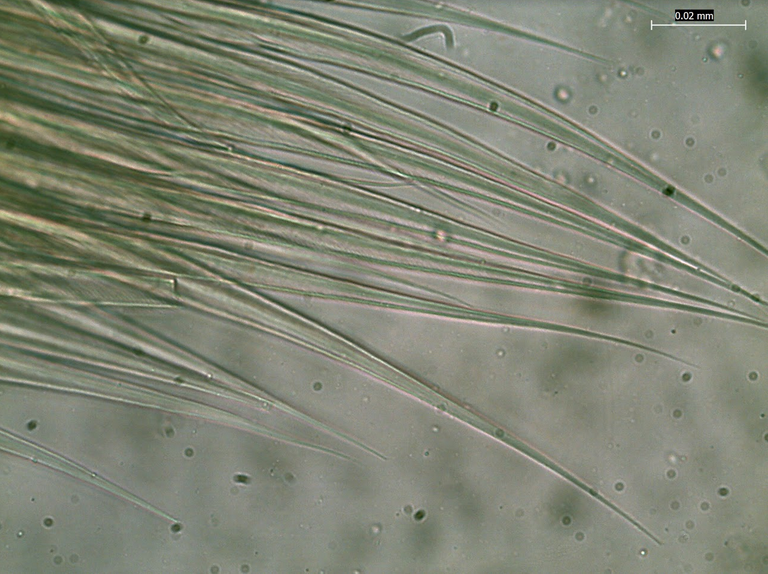

Photo's was very important. I used a camera that was installed onto the Light microscope to take pictures which automatically loads the photos on the computer. The photo below I took with the microscope camera.

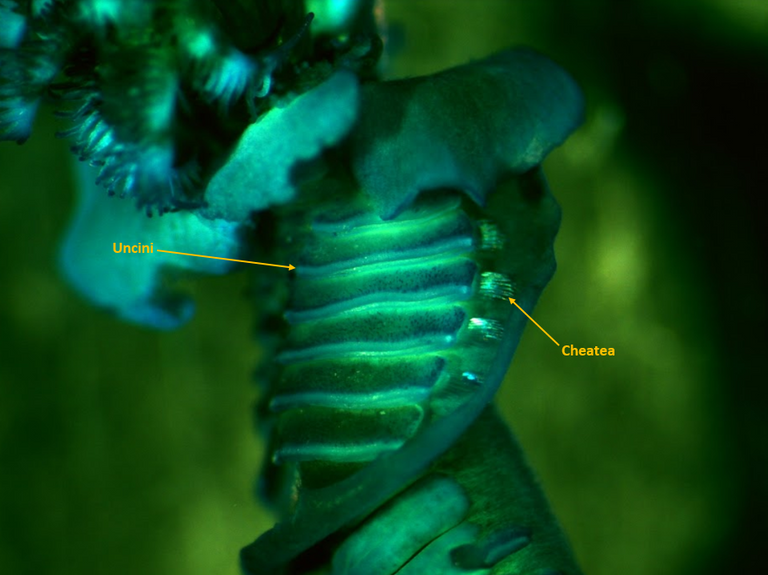

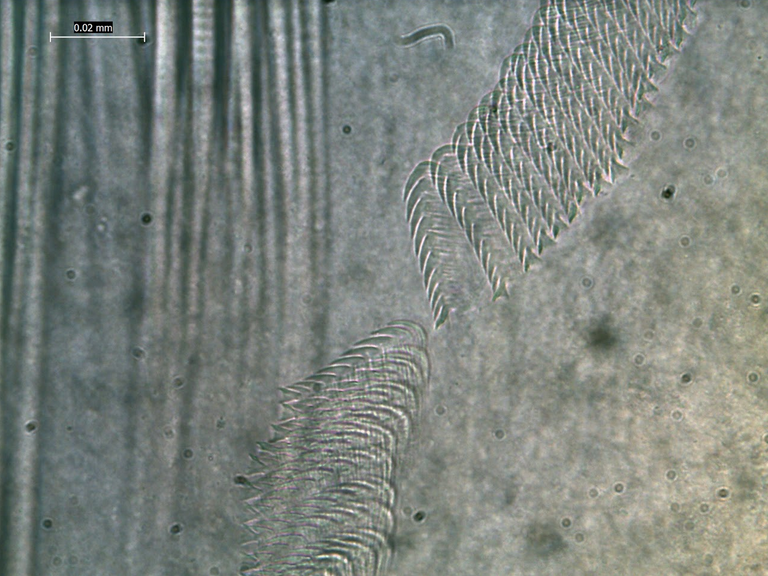

The specimens that I described I placed in separate eppendorf's with tags. Damaged specimens weren't used for description, but for making slides. To do this, I had to cut small portions of the worm out and mount it on a glass plate. Through a Slide Light microscope I could describe the cheatea (the 'hair') and I was able to count the uncini (the 'teeth'). The uncini are situated on every segment as a white-ish line.

And the cutting starts...

.jpg)

I created a database with all the description and sent it to Doctor Simon as I finish a batch of specimens. From there Doctor Simon transferred the data into an Article, which is still in the process of being published.

Even though I didn't work in a Botany lab, I gained lab experience for which I will always be grateful for.

I made a Christmas card at the end of the year (Dec 2017), specially for my Doctor:

Stunning post! You are a genius. Keep it up!

Thanks for the comment 😊

Sea worms are so cool! I'm really happy you've shared your experience with us <3 AND CONGRATS ON THAT ARTICLE. I'm really hyped because I love the scientific side of steemit (and on other social networks because I'm a nerd) and this has brighten up my day, thank you :)

I've seen a few preserved sea worms in the Animal Biology lab I worked in the last three years, I only know their families, Serpulidae and Sabellidae, aaaaand Hermodice carunculata. Even though they're in ethanol, they still look really cute :)

Don't worry, I'm a nerd aswell. I'm glad you enjoyed my article and that I could brightend up your day with worms.

I've never seen a Hermodice carunculata, and googled it now. They look sooo cool! Now you brightend up my day.

.jpg)

Thanks for your comment and sharing of new knowledge 😊

@kiekie this looks like meticulous work. I am glad you took the time to share your experience with us! It must be fascinating to use a light microscope. That close up of the worm through the microscope strangely resembles a snowflake.

I just read an article about earthworms this morning. Are sea worms as important for the ocean floor and food chain as earthworms are for the soil and land ecosystems?

Yes they are, they both are designed to clean their environment. This specific worm, S. krausii, is a filter feeder and it keeps the water clean by filtering out ('eating') organic and mineral paricles. Without these filter feeding worms, the marine environment will become 'dirty' and other sessile organism can smother to death. The earthworm have a similar task, as you know. Without them the soil won't be fertile or oxygenated for plants to grow in.

My dad is currently working with earthworms, giving them dead soil to enrich again. I also find the earthworms fasinating!