I'm afraid this is the situation of the coffers, monsignor.

Are you telling me Hugues that I must defend the Holy Sepulcher with only a few talents for 300 knights?

I'm afraid that's the way it is, monsignor. We are isolated in Jerusalem. The 2,000 Christian souls under your protection barely generate income. The access to the coast is too risky and ...

Enough. I have understood it.

Godefroy de Bouillon walked up and down the room before de Montfort's watchful eye. Finally, in a barely audible sigh, he muttered:

- God knows we do not live with luxuries precisely, but let's do His will that He will provide. What do you propose, Hughes?

De Montfort was waiting for that question and had prepared his answer:

Monsignor, the payments of the gentlemen can be divided, in such a way that they charge only one tenth here and the other nine are payable back home. Your properties are already mortgaged with Jewish merchants from Luxembourg and Flanders and local Jews act as correspondents for them. They would charge you an interest, but I estimate that they would allow you to refinance this item for another year.

Really the ways of the Lord are inscrutable! That those who made him crucify pay now for his betrayal!

You really pay, monsignor ...

De Bouillon was so busy breathing with relief that he did not hear, or did not want to hear, his counselor. Hughes de Monfort, he continued in a somewhat more audible voice.

Then there's the matter of current expenses ...

Why are you stopping? Keep going!

De Monfort swallowed. He reached the most sensitive point for de Bouillon, his pride, what he called the "mercy of the returned Lord".

De Bouillon had sent for the construction of St. Peter's Hospital on the outskirts of Jerusalem, on the other side of the Kidron, in the same place where the wounded had been treated during the siege of the city. Later he had taken charge of the pilgrim hospital of San Juan near Via Dolorosa, with the idea of attending to the inhabitants of the city. He wanted to symbolize with these actions the universal mercy of the Lord, who had treated Christians and non-Christians alike, and used all available doctors, including both Jews and Muslims, under the direction of the Hospitaller Knights, a self-proclaimed Order. of Saint John of Jerusalem commanded by Gérard de Martigues.

De Bouillon, who had tortured de Martigues after the fall of the city on suspicion that he collaborated with the enemy, now professed to him if not affection, if a great respect for his piety, his organizational capacity and his intelligence. For that reason, de Monfort found the situation especially thorny. Any proposal that could affect the Knights of San Juan, Gérard de Martigues could contrive to turn it against him. That is why he had conscientiously prepared his arguments.

- Monseigneur, God knows that we can not live more austerely than we already do. That is why we only have to close one of the hospitals that Monsignor so generously supports ...

The look of Godefroy de Bouillon would have petrified another who would not have been Hughes de Monfort, who continued with his eyes fixed on the ground.

- I looked at the numbers. The Hospital of San Juan has treated 2100 people in the last year, of which 630 have died, 30 out of 100. The San Pedro Hospital has 800, of which 160 have departed from this world, 20 out of 100. We have to close San Juan and focus our scarce resources in San Pedro. It is a pure matter of effectiveness.

The Defender of the Holy Sepulcher stared de Montfort in milestone, in silence. After a time that seemed eternal, he spoke:

- I'll get Martigues and tell him.

II

That is, Monseigneur, if I have understood Monsieur de Monfort well, you intend to close San Juan simply because 30 of every 100 patients have died in it, while in San Pedro 20 of every 100 have died. And this, of course, it is, that the sick and wounded were equivalent.

That's right, Martigues, we do not have money for more.

What if I found a way to show you that the decision is not so obvious? Would not it be a sign of the power of our Lord that, using your same numbers, I showed you the opposite?

That is not possible! - screamed de Monfort

It is, my lord de Monfort. If Monsignor authorizes me, I will call Edward who is down with the horses, he will know how to explain it to you.

Edward? Simme's son, the British smith?

That same one, monsignor.

Well, tell him to go up. It will be fun!

While Martigues went out to look for Edward, de Monfort went over and over again his numbers and lists, knowing himself observed by de Bouillon, who enjoyed finding a way to give him back something of the intellectual arrogance with which de Montfort treated him. That and the pleasure of finding an excuse not to close any of the hospitals.

Monsignor, with your permission, here is Edward Simmeson

Come in, come in, do not be afraid. And tell me Edward, where did you learn numbers? No doubt it would not be with your father shoeing horses.

No, monseigneur. A hermit who lived in a park near the village of Blechelegh (he pronounced it "bletchli") taught me how to read, write and how little I know about numbers.

OK OK. Did Mr. de Martigues explain the matter?

Yes, monsignor.

And do you think you have an answer? Look, there's a lot at stake.

Yes, monsignor. In hospitals, I'm the one who keeps patient records. I have studied the data and I have elaborated, with the help of God and San Juan Bautista, an interpretation of the interaction in the contingency tables that will allow me to give a fulfilled answer, and to your entire satisfaction.

Praise be to God! I do not understand anything of what you say! But explain it well here to Monsieur de Montfort, who is the one who keeps the accounts - he finished off with Bouillon with undisguised sarcasm.

Edward approached the center of the room. Through the balcony without curtains you could see the church of the Holy Sepulcher, muttered a prayer and looked at his master. De Martigues nodded imperceptibly, inviting him to speak confidently.

Mr de Montfort, consider for a moment that in the two hospitals in Jerusalem we treat both men-at-arms and civilians. Well, in San Juan we cared for 2100 people, 600 inhabitants of the region and 1500 warriors. Of them, 60 civilians died, that is, 10 out of 100; and 570 milites or, which is the same, 38 out of 100.

What I was saying! An atrocity!

Let me continue, sir. In San Pedro we attended 800 people, 600 civilians and 200 men in arms. 80 people died, or what is the same, something more than 13 people out of every 100, and 80 milites, that is 40 out of 100.

As you can see - Martigues interrupted with a smile from ear to ear - the numbers match with yours, de Monfort, but in San Juan die 10 and in San Pedro 13 out of every 100 civilians, and as far as milites in San Juan 38 out of 100 out of 40 in San Pedro. In both categories San Juan can be considered a better hospital, if this is conceivable.

But, but ... my numbers ...

No sputtering, de Monfort, you make me laugh and this is very serious - managed to say Bouillon between laughter. Well, based on these considerations I can not close any hospital, there is no argument for it. You will have to find where to cut expenses elsewhere. It occurs to me that you could start by reducing the number of your servants ...

The Defender of the Holy Sepulcher, visibly satisfied, accompanied the two hospitable gentlemen to the exit of the palace-tower on their way to the evening Mass.

This artifice with numbers is too good to miss without a proper name ...

The hospites that know her call it the paradox of Simmeson, monsignor.

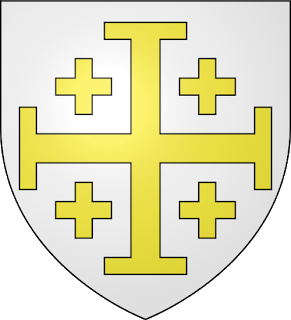

I think it's appropriate. Although it is difficult to pronounce, starting today will be Simpson's paradox. Go with God!

This story was originally published on August 2, 2013 in the Scientific Culture Notebook.

You got a micro upvote from me 😎