Wu Chien-Shiung was ‘The First Lady of Physics,’ but her work was largely unacknowledged

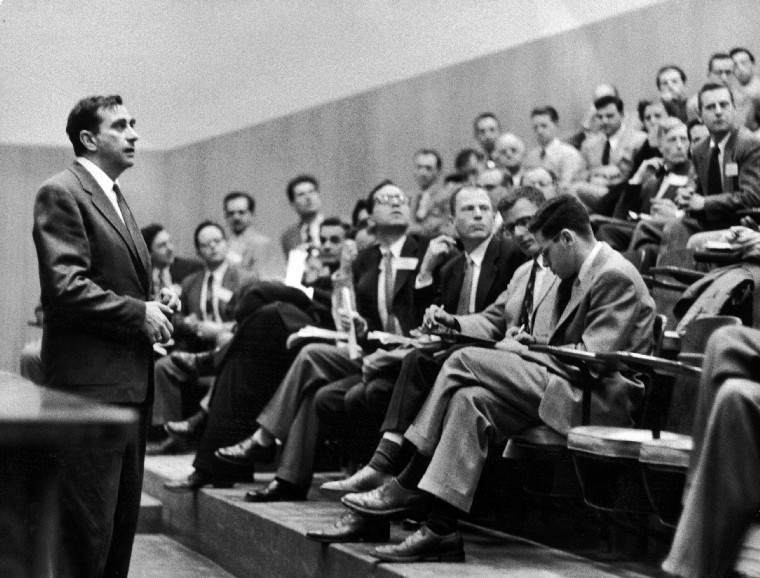

(Physicist Dr. Wu Chien-Shiung standing with tubes from a particle accelerator at Columbia University in 1963.)

When her ocean liner, the President Hoover, docked in San Francisco in 1936, Wu Chien-Shiung was surprised to find that discrimination against women was par for the course in the United States. She was told that female students at the University of Michigan, where she was soon to begin as a doctoral student, were not even permitted to use the front entrance of a brand-new student center; they had to scuttle quietly through a side door. It was a problem the “First Lady of Physics” would run up against again and again: when UC Berkeley refused to hire her despite an outstanding performance as a student and researcher, when Columbia University took eight years to promote her, and when the Nobel Prize in physics was given to her two male collaborators for their work in parity nonconservation but not to her.

“US society and families unfortunately believe that science and some other fields are exclusively men’s turf,” she told Newsweek in a 1963 interview. “In Chinese society, a woman is measured solely by her merit. Men encourage them to succeed, and they do not have to change their female characteristics in doing so."

Or at least that was what Chien-Shung had been taught. Growing up in Liuhe, China, a small village near the mouth of the Yangtze River about an hour north of Shanghai, Chien-Shiung was encouraged to partake in intellectual pursuits alongside her brothers early on. Her father was unusually progressive for the time. He fought in the Shanghai Revolt in 1911, which overthrew the Qing Dynasty and led to the founding of the Republic of China, and when peace was restored to the countryside, he returned home to found Ming De Women’s Vocational School. Wu, who attended the school as a child, was her father’s curious and eager companion, absorbing the scientific news articles he read to her even before she could read herself, and was fascinated by world news broadcasts on the family’s primitive quartz radio.

At age 11, Chien-Shiung left Liuhe to take the entrance exam for a prestigious high school for teachers in training. She ranked ninth out of the 10,000 applicants that year, and news of her intellectual prowess spread quickly on campus. She was well liked by her peers, but Chien-Shiung was a serious and determined student who preferred study to leisure with friends. In 1929, she graduated at the top of her class and was permitted to go straight to university instead of teaching for a year, as the school normally required.

Chien-Shiung graduated from National Central University with an undergraduate degree in physics in 1934. Two years later, she said goodbye to her family and sailed to America. She never saw her father again.

When Chien-Shiung learned about the scope of gender disparity in the U.S. upon her arrival, she decided not to continue onto the East Coast but to study instead at the liberal University of California at Berkeley. Though its history was not as impressive as those of some Midwest and East Coast institutions, the radiation laboratory (and the faculty’s recent addition J. Robert Oppenheimer, the future “father of the atomic bomb”) was. Though he had a reputation for discriminating against women and foreigners, the head of the physics department, Raymond T. Birge, agreed to allow Chien-Shiung into the program.

At Berkeley, she survived on 25-cent meals she negotiated at a local Chinese restaurant. She made close friends but had little time to socialize, preferring to work in the lab some nights until the sun rose. One of those friends, Luke Yuan, had come from China just weeks before Chien-Shiung to join the physics department’s doctoral program. The pair were married in 1942.

Wu was still at Berkeley when Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann discovered uranium fission in 1938, shaking the field of physics — and the world — to its core by making nuclear weapons possible for the first time in history. Her previous research, as described by Chiang Tsai-Chien in Madame Wu Chien-Shiung: First Lady of Physics Research, was in the investigation of decaying radioactive materials, but, following the groundbreaking discovery of uranium fission, Wu shifted her research, conducting a series of experiments on the products of the process.

As Chien-Shiung completed her degree, the U.S. government was considering how to deal with the now increasingly real possibility that an already dangerous and violent Germany might develop a nuclear bomb. Acutely aware of the threat, in 1941 President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved an atomic program that enlisted the minds of the country’s top physicists, including Oppenheimer. Chien-Shiung was making waves in the scientific world, being hailed as the “Chinese Madame Curie,” but it wasn’t enough to get her either a place in the project or a teaching position at Berkeley. In 1943, she moved east to be closer to her husband, who had landed a job in defense research in New Jersey.

By

1944, the Manhattan Project had made significant strides toward the development of a nuclear weapon, but there were still some critical problems to solve, including how to concentrate uranium to the point of critical mass necessary to detonate the bomb. Chien-Shiung, in her work at Berkeley, had come up with some results that could take the researchers in the right direction. The project requested that Chien-Shiung hand over a draft of her research, and, with the help of her experimental results, the United States successfully tested its first atomic bomb on July 16, 1945.

Chien-Shiung had mixed feelings about the role of her research in the development of nuclear weapons. On the one hand, she was troubled by the devastation the bomb had wrought. On the other, she hated to hear of the suffering of the Allies and was even more disturbed by the misery endured by her family and countrymen in China due to the onslaught of the Japanese. Many believed at the time (and continue to believe today) that the loss of life caused by the bombs the U.S. dropped on Japan was far less than what might have occurred had World War II continued. Publicly, Chien-Shiung rarely talked about her involvement in the Manhattan Project, but in a meeting with the Taiwanese president in 1962, she advised the country not to embark on a nuclear program.

In 1944, Chien-Shiung joined the faculty at Columbia University and became the leading world authority in the study of beta decay, a radioactive process in which an electron or positron (a beta ray) and a neutrino are emitted from an atomic nucleus. It was because of her expertise in beta decay that Chien-Shiung was approached in 1956 by two theoretical physicists — Tsung Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang — to devise an experiment to prove that during beta decay the “law of conservation of parity” (that objects and their mirror images behave the same) did not apply. It was Chien-Shiung’s experiment that proved the theory, but Lee and Yang alone received the Nobel Prize the following year, and her work went unacknowledged by the Nobel committee.

Despite the painful slight by the scientific community, Chien-Shiung went on to win a number of international awards in physics, including the Comstock and Wolf prizes, and continued her work at Columbia University until 1980. She became the first woman elected president of the American Physical Society, in 1975.

In 1997, at the age of 84, the First Lady of Physics passed away in New York. In accordance with her final request, she was buried in the courtyard of the Ming De women’s school in her home village of Liuhe, a symbolic reunion with the father she adored.

At Timeline, we reveal the forces that shaped America’s past and present. Our team and the Timeline community are scouring archives for the most visually arresting and socially important stories, and using them to explain how we got to now. To help us tell more stories, please consider becoming a Timeline member.

Congratulations @rogilliuz! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.