In summer of 1930, after receiving a scholarship to write his dissertation at Cambridge, a young alumnus of the University of Madras Subramanian Chandrasekhar was sailing from India to England. The trip was a long one and Chandrasekhar had enough time to contemplate about a problem that occupied him for a long time – how a star behaves as its fuel slowly burns out. While such star lives, the radiation can resist against the gravity pull that squeeze it, but when nuclear reactions stop, the pressure from the radiation disappears and the star falls under the reign of gravity. What fate awaits this star?

By skillfully applying his knowledge in special theory of relativity and quantum statistics Chandrasekhar calculated his famous limit, later named after him, - the upper limit of mass for star to exist as a white dwarf (right now, we believe that it is 1.44 solar mass). When the limit is passed, the body becomes a neutron star. Far more massive stars, as discovered later, turn into black holes. However, Chandrasekhar was not interested in black holes – their time had not yet come.

Chandra in his early years, The University of Chicago

In Cambridge Chandrasekhar continued actively develop his ideas and acquainted with great sir Arthur Eddington who often was a guest in his cabinet. Regularly, they dined together. Chandrasekhar also established close contact with another outstanding astrophysicist – professor Edward Milne. Unfortunately, Eddington had a hot scientific conflict with Milne just about white dwarfs and neutron stars. The contents of the conflict do not matter today, but one can judge how heated was the discussion by one of Eddington’s quotes: “My interest in the best [Milne’s] paper is dimmed because it would be absurd to pretend that there is a remotest chance of his being right”.

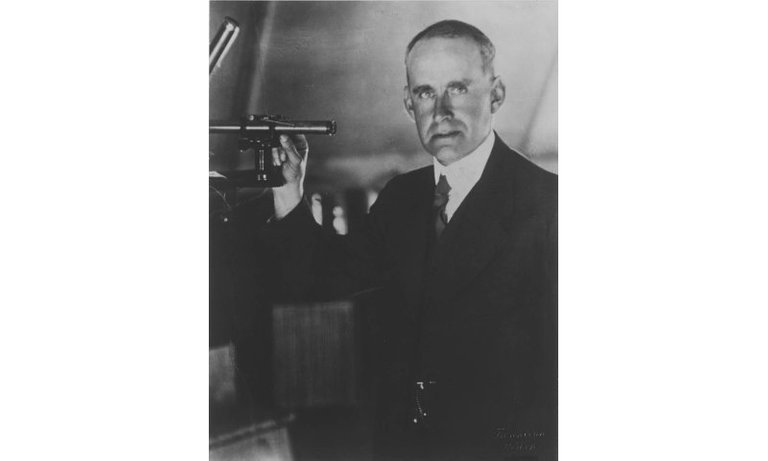

Arthur Stanley Eddington, Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology

Disastrously, Chandrasekhar’s results evidenced both for Eddington’s hypothesis and Milne’s hypothesis. As a result, he ended up between two fires: the very fact that his conclusions supported their rightness was eagerly accepted by both opposing scientists as a given, but those evidences that supported the ideas of one of them irritated both of them. The young aspirant found himself between a hammer and an anvil. However, he was certain that his ideas and results were legit and decided to present them in front of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The meeting where Chandrasekhar wanted to declare his report was scheduled for January of 1935. After receiving the program, Chandrasekhar was genuinely surprised to see that right after him Eddington will present a report of his own on a similar topic. Both scientists saw each other daily, but Eddington never mentioned a word about his report. When asked asked about it directly by Chandrasekhar, he Eddington said that it was a surprise. A surprise that the Indian physicist could not forget even 50 years later.

After the Chandrasekhar’s solid report (sir Arthur asked the society to give him a half of an hour instead of usual 15 minutes), Eddington made sure to meticulously destroy every single conclusion made by Chandrasekhar. He was close to ridiculing “Chandrasekhar limit” (although, it did not have that name back then) and having from little to no weighty arguments announced that he was not sure if would ever leave the meeting “alive”, but he was sure that “relativistic degenerate gas” does not exist. Note that relativistic degenerate gas and its very existence were the foundation of Chandrasekhar’s argumentation. Eddington also talked about the possibility of a star turning into either a white dwarf or a neutron star: “Various accidents may intervene to save the star, but I want more protection than that. I think there should be a law of nature to prevent the star from behaving in this absurd way![…] The [Chandrasekhar’s] formula is based on a combination of relativity mechanics and non-relativity quantum theory, and I do not regard an offspring of such a union as born in lawful wedlock”.

Chandrasekhar was devastated. One of his idols who was well informed about his results and who was seeing him nearly every day said nothing in private, but decided to humiliate him publicly in front of the whole Royal Astronomical Society. The strike was rough and way below the belt. Eddington’s authority was so huge that a young aspirant had no hope of overcoming him. However, Chandrasekhar decided to keep fighting.

He needed a famous scientist who could double-check his equations and either prove that he was right or point out a mistake. A single word from Niels Bohr, Wolfgang Pauli or Paul Dirac would have been enough to acquit and whiten the young aspirant in the eyes of his colleagues. Chandrasekhar immediately wrote to his old friend, a famous physicist and Bohr’s assistant Leon Rosenfeld, with a plead to show his math to the maître. Rosenfeld soon replied, excusing for Bohr being busy and unable to write himself, that Bohr did not find any mistakes in Chandrasekhar’s conclusions and was completely confused with Eddington’s objections.

This was more than enough to reinvigorate the young aspirant, but the support was in a private letter. He needed something weightier. He sent to Rosenfeld several articles criticizing his works written by Eddington. However, Rosenfeld advised him to stay away from public confrontation hinting that it could harm Chandrasekhar despite his being right. About Eddington’s work he wrote: “I bravely read Eddington’s articles twice and my previous opinion have not changed – this is a complete nonsense!” However, neither Bohr nor Rosenfeld or Pauli (who was also familiar with Chandrasekhar’s work and Eddington’s objections and took the side of the young aspirant) were not leaning toward publicly opposing the ideas of the leader of British astronomers. All of them mentioned that the discussion was fielded in Astrophysics and they were no astrophysics specialists and should not publicly talk about it.

With such a situation at his hands, Chandrasekhar decided: “Either I will fight to prove that I’m right until the end of my days or I will change the area of my research. I decided to write a book describing my results and focus on something else”. He did exactly that. The book was published soon after he successfully presented his dissertation.

Despite this unexpected and unpleasant incident, sir Arthur and Chandrasekhar continued to remain a good relationship. It seemed that Eddington did not see anything wrong in his deeds following an ancient credo “Amicus Plato, sed magis amica veritas”. The scientists infrequently met. After Chandrasekhar moved to States in 1937, they continued to write to each other until Eddington died in 1944. Eddington’s letters were infusd with warmth and humor. Chandrasekhar answered in the same manner and up until his own end regarded sir Arthur as a great scientist and decent man.

In 1983, nearly 50 years after his discovery, Subramanian Chandrasekhar was awarded with Nobel Prize in physics for his theory of the evolution of massive stars. In 1995, he died. 4 years later, NASA launched a space X-ray observatory named after him. Estimated for a 5-year lifespan, it served for more than 15. Thanks to the observatory, we received valuable information that proved many Chandrasekhar’s theoretical estimations.