Popular expectations for the future are helplessly colored by present trends. The assumption is always that whatever’s going on now can be safely extrapolated into the future along a linear (or, per Kurzweil, logarithmic) curve. So it was that during the space race, baby boomers took for granted that we’d have fully colonized the solar system by the year 2000.

Likewise, during the dawn of information age when computers began appearing in homes across the US, then connecting to one another by way of an internet still in its infancy, people envisioned a cyberpunk future. What they saw happening around them, but more, bigger, faster.

Every generation extrapolates naively, imagining they’re different. Imagining that because they have access to more information than prior generations, they won’t make the same mistakes in their predictions. Yet every generation is nevertheless taken by surprise. The information age took baby boomers by surprise, and the biotech age will take millennials by surprise.

In each case the seeds of the next revolution were already planted and gestating while the public’s attention was elsewhere. DARPA was experimenting with a rudimentary precursor to the internet back when baby boomers were glued to their televisions watching the Apollo program unfold.

We’re no better, eyes still fixed firmly on progress in computing, robotics and AI while the groundwork for a biological singularity is being laid in labs around the world. The UN passed a declaration condemning editing of the human genome way back in 1993, but the UN is a toothless animal many nations pay no mind to, China least of all.

Back in 2018 news broke of efforts underway at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen to genetically engineer “super babies”, lacking a gene called CCR5 which makes us vulnerable to a variety of diseases. The best information available indicates these pregnancies reached 2 weeks, but there’s no word as to whether they were ultimately aborted or carried to term after that point.

More recently He Jiankui, a biophysicist involved in the creation of the first gene edited babies, was sentenced to three years in prison for illegal medical practice. So, it remains to be seen how committed China is to this field. What this project demonstrates however is that the genie is nearly out of the bottle: Genetic engineering of humans is possible already, and while He Jiankui’s project was arrested, others will undoubtedly slip through the cracks.

How does this loop back to the singularity? In many circles it’s taken for granted that we will eventually create conscious machines able to engineer even better offspring, setting off a feedback loop, an outward spiral of mental growth you might call an “intelligence explosion”. But as of this writing it remains unclear whether a conscious machine is a realistic near term possibility.

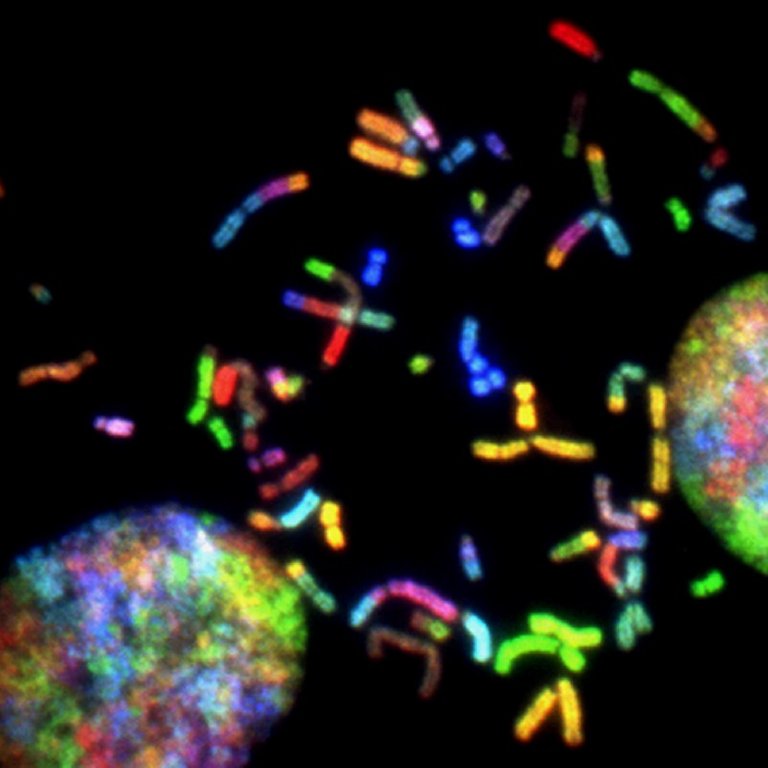

We know for certain that biological consciousness is possible, because that’s what we are. We now have the toolset to begin attempting to increase our own intelligence. Do the principles of the singularity not also apply here? If we create a generation of unusually intelligent children, and some grow up to study genetic engineering, should we not expect them to be more effective at it?

Would this not also set off the sort of runaway intelligence explosion Kurzweil and his followers expect to happen with AI? Being that we’ve already got functional, conscious bio-intelligence as a starting point (as well as the toolset needed to improve upon it) should we not expect the bio-singularity to happen sooner than the techno-singularity? What would that even look like?

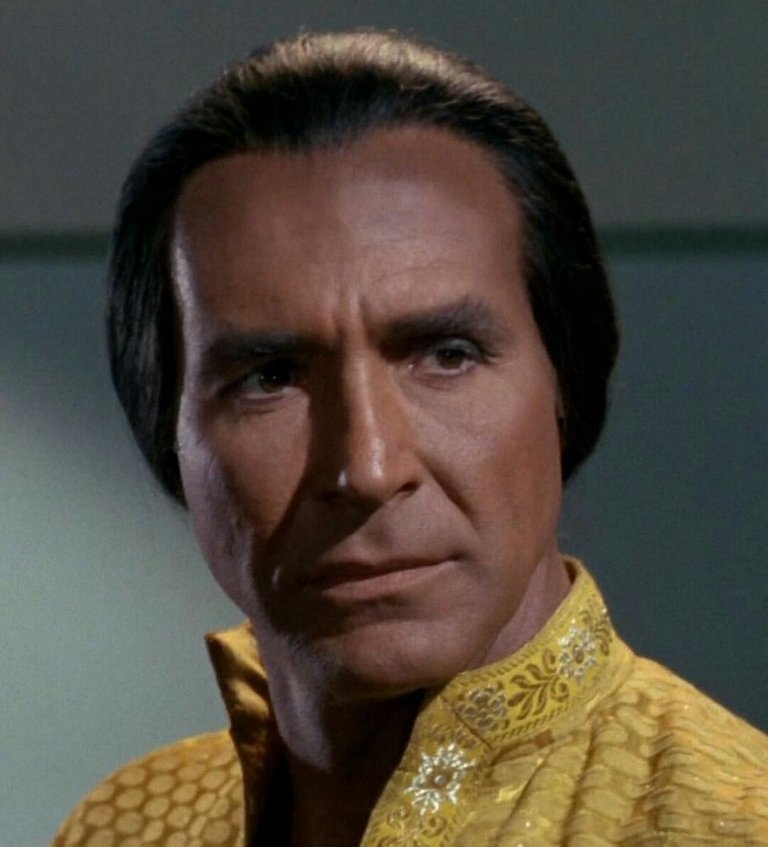

Depictions of engineered superhumans in fiction have typically been unflattering. The eugenics wars from Star Trek canon address this topic, but as it was imagined in the 1960s, they hadn’t foreknowledge of genetic engineering. If we set out to improve human intelligence by selective breeding there would be little to worry about, as meaningful results would be centuries away. But I digress.

Gene Roddenberry, for all his imagination and forward-looking ideas, was in some respects a very small minded man. Any development that would fundamentally change the human experience frightened him, so it was contrived in Star Trek that transhuman technologies were simply forbidden.

Infinite diversity in infinite combinations…but nothing too scary or weird. Roddenberry wanted a future in space, but he wanted garden variety humans as he knew them to be the ones inhabiting that future. Explorations of genetic engineering in Hollywood have been similarly pessimistic.

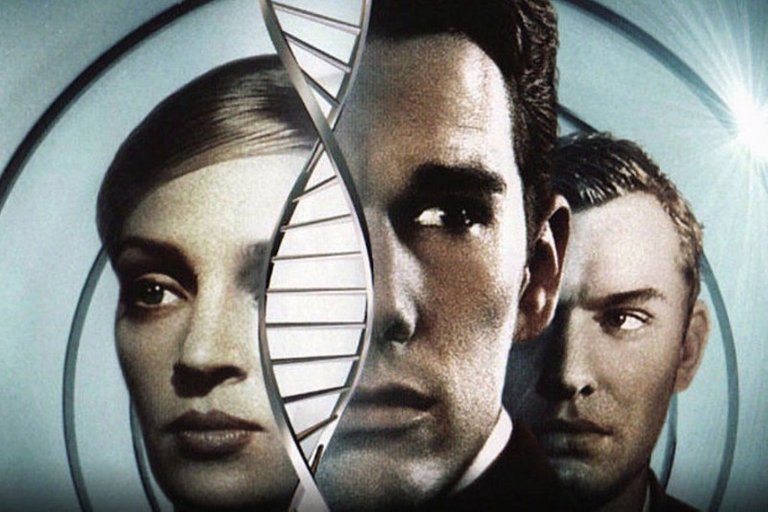

GATTACA seems to dominate the public consciousness where the topic of genetically engineered humans is concerned. It reliably comes up in any discussion of CRISPR as a cautionary tale. Surely as Roddenberry feared, genetically superior humans would dominate and subjugate unmodified humans? It happened in the film after all.

Then again, if we chose how to proceed based on lessons from films, we should abandon spaceflight. After all, look what happened in Gravity. There’s no shortage of science fiction films where spaceflight ends in disaster. Likewise we should scuttle Aquarius Reef Base and abandon plans for Proteus, because of all the science fiction films set underwater where the habitat inevitably floods or implodes by the end (to say nothing of Bioshock).

Fear of the unknown is the oldest, most human impulse. It is only because curiosity sometimes overpowers fear that you’re reading this on a computer from inside a climate conditioned structure, rather than painted figures on a cave wall, dimly lit by a nearby fire.

Speaking of our protohuman ancestors, undoubtedly if they knew how radically different humanity would become, it would frighten and concern them. They might regard us as illegitimate impostors. Usurpers of their throne. Certainly neanderthals would.

Should we therefore have never evolved to this point? Were our distant, hirsute, simian ancestors the true humans that we wickedly replaced? Certainly not. Why then should we regard CRISPR transhumans with fearful jealousy, not wanting to be replaced with a humanity that is intellectually as far beyond us as we are beyond our cave dwelling ancestors?

This fear is usually framed as ethical responsibility. But if you remove that mask, you reveal it for what it is: Small minded selfishness. The desire for humanity as we are now to remain forever unchanged. The be-all, end-all apex of intelligence, never to be surpassed. What a depressing dead end to intentionally trap ourselves in.

For some reason it’s far less common to encounter this advocacy for intentional stagnation in techno-singularity circles. The same fearful predictions that we will be annihilated if we create our own superiors can be seen in films like Terminator, Ex Machina, The Richard Forbin Project and more. But there are equally numerous optimistic depictions of benevolent AI which rewards us for creating it, which becomes a caretaker to humanity and facilitates our greatest ambitions.

Optimistic depictions of bioengineered humans are considerably more rare, perhaps because we know ourselves too well. We are tyrants, tormentors and exploiters just as often as we are saviors and custodians. It is, from that perspective, understandable that most people don’t have much faith that increasing human intelligence would reduce aggression, prejudice, elitism or any of our other shortcomings (though I think they’re likely mistaken).

Even if human nature is unchanged by an increase in intellect, what you get is much the same humanity that we have now, except with an improved capacity for problem solving. Given the severity and complexity of the problems we face as a species (such as pandemics and climate change), buffing our INT stat doesn’t seem like the worst idea in the world.

The caveat is that, as with any explosion, it’s immediately out of our control the moment after we set it off. Even as a proponent of genetic transhumanism, I can’t sugar coat this point. We can control the traits of the very first generation of CRISPR babies, choosing the direction of our first step into a post-evolutionary future, but we won’t be the ones choosing any of the subsequent steps.

But then, isn’t that true anyway? Isn’t every generation eventually superceded by the next? No longer steering the world, no longer calling the shots, replaced by a new set of people with new thinking who will decide where society goes from that point onward? What would a bio-singularity fundamentally change about this transition, except to accelerate it?