photo: sfsafehouse.org

It is sometimes difficult for people to think outside of the lens of individualism.

The notion of the "individual" may appear as common sense to modern Western readers, but in sociology we recognize it as culturally and historically specific. That is, the concept of the individual is not present or important in many cultures. The notion of the individual (as the building block of society) did not exist for most of human history. As one sociologist, Steven Buechler, puts it, "Although societies have always contained people, the notion that people are 'individuals' with unique functions, personalities, and temperaments is historically new."

The rise of the individual to center stage is linked to massive upheavals of Western society: the transition to capitalism and industrialization, on one hand, and political revolution and modern democracy on the other. Enlightenment thinkers and free market philosophers famously extolled the virtue of "freedom", "individual rights", and "rational" thinking. These symbols still ring through our basic assumptions about life and work today. They are the foundation of our most important political documents. History is taught in this context as a narrative of individual characters and decisions. And we often debate public issues like crime or health or economics in much the same way, as a set of choices made by individuals.

Think of that familiar cultural narrative, the American Dream, which teaches generation after generation of citizens about the virtues of individual determination and work ethic. Statistically speaking, this is not a reality for the majority of Americans. Social mobility is very low in American society. Full-time employees earning minimum wage-- even the most entrepreneurial and hardest of workers-- still live below the poverty line. Women and minorities are disproportionately represented among the Working Poor, revealing the lasting legacies of discrimination and challenging the ideals of meritocracy so fundamental to mainstream American culture.

(photo: IdiotsGuides.com)

And yet, the idea of the American dream remains strong.

This idea of the individual as the starting point, the essence of life, and the reason for our circumstances appears as simple taken-for-granted common sense. When I teach sociology, I am mindful that it is not always easy for new students to think beyond the realm of individualism. Doing so affects (and maybe even challenges) their very view of the world.

But the fact remains: humans are social beings. We are socialized into norms, values, and worldviews that are also built into our institutions. Certain behaviors are reinforced as society teaches us to conform. No one conforms to society all the time, but the pressure to do so is strong. There is no real pure form of "free will" in this sense because we are always contending with social rules and norms.

Don't get it twisted, though. Accounting for social forces does not deny human agency. Humans do make decisions and choices, and our motivations do affect our realities, but nobody does this in a bubble. Our interpretations and thought processes are affected by our social environment. And vice versa-- we as individuals can and do affect our environments.

Good sociological theory, based on empirical research, accounts for both the individual and social forces.

I often notice what Buechler calls "the glorification of the individual" in conversations among strangers, media explanations of events, and those sometimes-tense, sometimes-friendly discussions with family during holiday celebrations. When individualism takes center stage, structural issues tend to get dismissed. We focus on the choices or personality traits of the homeless person, the personal racism of one "bad apple" police officer, the psychological profile of the mass shooter or domestic abuser, or the entrepreneurial spirit of the CEO.

The person involved is an important part of the story, sure, but what do we ignore when we use this frame of reference alone? As a sociologist, my focus is on social forces.

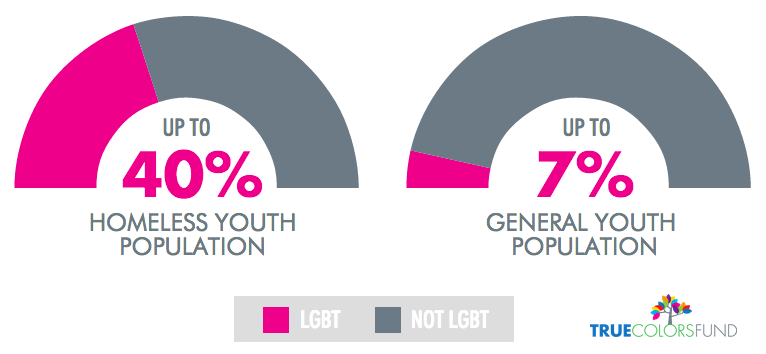

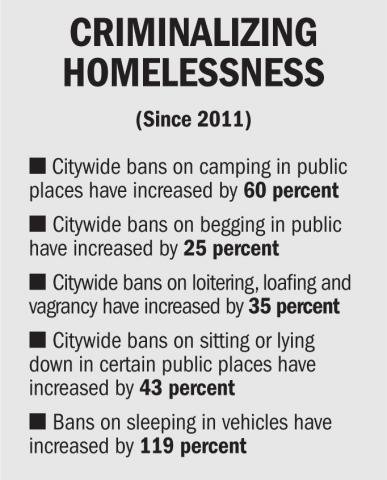

Forty percent of homeless youth are LGBTQ. A study in 2007 found that one in four homeless adults are veterans. There is a strong geographical relationship between high rates of homelessness and lack of affordable housing. The latter has been significantly defunded across the country since the 1970s, and many cities have resorted to criminalizing homelessness-- a practice that A) is more costly to taxpayers than offering affordable housing and B) exacerbates the problems for homeless individuals by adding criminal records and legal fees to their already dire circumstances.

Source: National Law Center on Poverty and Homelessness

These are just a few glimpses of social forces, but there are countless more in the scores of sociological research on homelessness. Such cultural and structural facts reveal that there are forces at play beyond the reach of any one individual.

I will return to the other examples I pointed to above as I continue my journey on Steemit, so I'll save those cans of worms for another day. For now, the point is that putting an individual's experience in a broader social and historical context gives us a more complex picture and a better chance of dealing effectively with any social issue.

Discussion/ thinking exercises:

- Imagine I asked you to tell me the story of your life. Instead of telling me from your point of view alone, though, I would like you to think about the social forces that affected your life. What groups, organizations, and institutions shaped your experiences? How did historical changes or events, your cultural upbringing, your class position, your neighborhood or family, your gender/ race/ ethnicity etc. affect your life story? The story of your life will probably seem much different told in this way. It is still, however, the story of your life.

Whether or not you actually write anything down is not important. Just thinking about it should make clear that there were forces beyond your control that shaped you AND that your uniqueness, personal motivations, and choices were also important along the way.

- Suffering from depression or anxiety is a deeply personal experience, and for the most part, we as a society treat these issues on an individual basis. At the same time, the rates of these mental health issues have reached epidemic proportions. What social factors might be involved? Are there ways to "treat" the problem of depression/ anxiety on a scale beyond that of the individual?

Repeat this, using other issues like obesity, eating disorders, poverty, gun violence, domestic violence, sexual harassment, unemployment, addiction, etc. If at least some significant factors are beyond the control of the individual, these are examples of what sociologists call "social problems".

Further reading:

on the recent emergence of "the individual" in human history: Chapter 10 in Critical Sociology by Steven Buechler

on the differences between individualistic and collectivist cultures, from a psychological perspective: https://healthypsych.com/individualist-or-collectivist-how-culture-influences-behavior/

on homelessness and LGBT youth:

https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/press/americas-shame-40-of-homeless-youth-are-lgbt-kids/

https://truecolorsfund.org/our-issue/

on homelessness and veterans: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/study-veterans-make-up-1-in-4-homeless/

on the criminalization of homelessness: https://www.nlchp.org/documents/No_Safe_Place

hopefully you feel at home here. 😊welcome to steemit @jessij, best regards..

Thank you so much! I am trying to learn what I am doing :)

This is demonstrably false. The notion of the individual, even in the very narrow sense you seen to be using it, dates back at least to the Greeks, and the idea that for most of human history no culture possessed a similar concept is so bizarrely bigoted that I don't know what would possibly compel a person to believe it.

I appreciate your comment. I see what you mean bringing up the Greeks, but a couple points:

P.S. It seems bigoted to me that the West imposes its version of human nature ( individual first) on the rest of the world. We are better off seeking collective freedom from the modern state and capitalism --- The State and Capital love the concept of the individual. It undergirds the notion of "private property" and instills a driving force of competition among the masses. It was a notion, along with brute force, that allowed Western imperialism to spread around the world.

What evidence is there that no culture had even a notion of an individual prior to some date? The notion that individual persons have specific obligations, responsibilities, and entitlements based on their position within a social structure is common in cultures that predate contact with the West.

More to the thesis of your post, the idea that the notion of the individual is somehow singly responsible for negative social consequences is contradictory when those consequences are considered negative because of their impact on individuals. Homelessness, poverty, discrimination, etc - these are bad because they are things that degrade the experience of individuals in some regard. If they didn't negatively affect individuals, then they wouldn't be negative consequences, and you likely wouldn't care as much about them.

I sense the disagreement is mostly semantic and I am new to this, so I will try to be clearer. You say that "The notion that individual persons have specific obligations, responsibilities, and entitlements based on their position within a social structure is common in cultures that predate contact with the West." This is what I am saying---> these roles and responsibilities were/are BASED off of social structure. What I'm talking about is the Western tendency of putting the individual first (and often without even looking at the social structure).

People exist. That was not the point. That is why I quoted from a sociology textbook early in the post. The individual is a loaded term with historical implications.

The problems you mention are social problems because they have sources that go above the individual. Even if all the people in this country stopped discriminating in their personal lives, institutional discrimination (which is built into our neighborhoods, school systems, wealth) does not just go away. There are some social forces that are practicably untouchable to the individual. And without a collective response, we can't do much about them as individuals.

I also never said this word was solely responsible-- I mention that the notion of individual takes center stage only with the beginnings of capitalism. It is more of a cultural idea that fits the economic system. It keeps us seeing people as "others" and as our competition, blaming the vulnerable for their own problems. The peasants in Europe who lost common land to "private property" were kicked off both forcibly just as they culturally became "free individuals".