“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

– Ludwig Wittgenstein

Language fuels our brains, frames our thoughts and makes complex communication possible. The words, expressions and quirks unique to our language largely define how we see and understand the world. If you’re monolingual, that world has clearer limits. But in an age of borderless communications and global travel, it seems almost archaic to be limited to one language only – even if you’re lucky enough to speak a global language like English or Spanish as your mother tongue.

But is being bilingual – speaking two languages – or even multilingual all it’s cut out to be? Does it really open up the world to us when Google Translate can do so in one easy click? Can it make economies more successful, help us earn higher salaries, maybe even lead to a happier, more connected life? And is it, as popular culture likes to claim, the secret to bringing up super smart children?

The brain is a remarkably malleable organ. From birth to old age, it develops, adapts, learns and re-learns, even after being injured. Language is an essential component of how the brain functions throughout life, but just like the brain itself, science still doesn’t have a full picture of how language works its magic on those neural pathways.

Although the old belief that babies who are exposed to more than one language will end up confused, less intelligent or even schizophrenic has been debunked (yes, people really used to believe this), in recent years the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction: Books and articles tout bilingualism as a magic wand that will transform every child into a pint-sized, multitasking genius.

Dozens of studies, often quoted in the press, have claimed that, among other things, learning two languages in early childhood improves a whole host of cognitive abilities, making the brain more adept at switching between tasks, focusing in a busy environment, and remembering things. Learning and using two languages, these studies imply, clearly make children’s brains better.

But when a young researcher named Angela de Bruin, herself a bilingual, looked at hundreds of these studies in more detail, she discovered that these studies often significantly overstated the advantages, and presented inconclusive evidence as conclusive. The narrative that “bilingual is better” was becoming well established in popular culture, but de Bruin’s critical take on the research behind it showed that the benefits weren’t as clear-cut or universal as had been reported.

This is not to say that there are no benefits, and they may even turn out to be significant once the science catches up. And beyond purely cognitive skills, the social gains may be equally important. A recent study, for example, concluded that bilingual children, even kids merely exposed to a second language, were better at interpreting another person’s intentions by being able to see things from their perspective. This, the researchers inferred, made them more empathetic and better at understanding what the speaker meant.

An ability to empathize in this way provides a social advantage, but there is one more significant advantage to learning and speaking more than one language: It helps the brain stay healthy throughout life.

The brain, like any muscle, likes to exercise, and as it turns out, being fluent in two or more languages is one of the best ways to keep it fit and keep degenerative disorders like dementia at bay. In fact, bilingual people show noticeable symptoms of Alzheimer’s nearly five year later than people who are monolingual and only speak one language. That’s significantly longer than what the best modern medicines can offer. Amazingly enough, this advantage is noticeable even in people who are illiterate.

True bilingualism also offers a more specific and distinct benefit to those who regularly speak two or more languages at native level, and crucially, switch between them on a regular basis: The brains of Puerto Rican New Yorkers who used both Spanish and English in their daily lives were indeed more nimble and agile than those of monolinguals. A study of Singaporeans who grew up with and used their native Asian tongue and English regularly came to a similar conclusion. Bilinguals who didn’t often switch between the two languages or only used one languages in a limited setting like home, showed far fewer benefits.

The cultural case is also worth examining, as is answering this important question: Does speaking more than one language help us feel more connected to the world, or as Charlemagne once famously put it, “gain a second soul”?

Languages help us make sense of the world and can even influence the way we see and describe it, as a recent study examining German and English speakers shows. There’s also no doubt that a Finnish and Arabic speaker, for example, would describe the world differently. After all, Arabic hardly needs 40 words or expressions related to snow like Finnish does, and there’s likely to be a noticeable difference in how a Finn describes, perhaps even experiences, a winter wonderland as a result. Indeed, learning another language not only helps us see the world from a different perspective, but it can even impact the way we think about it. As Dr. Panos Athanasopoulos, an expert in linguistics and bilingualism, puts it: “There’s an inextricable link between language, culture and cognition”.

Many studies support this, showing that people who speak different languages score higher in tests that measure open-mindedness and cultural sensitivity and have an easier time seeing things from a different (cultural) perspective. Bilingualism, therefore, seems to make people bicultural (or multicultural if you speak more than two languages), a significant advantage in today’s borderless world and a vital skill when traveling and getting to know new cultures and people.

The benefits of bilingualism don’t end there, however. Studies in Switzerland, Britain, Canada and India, as well as our very own EF English Proficiency Index (EF EPI), highlight the financial rewards associated with bilingualism or multilingualism at all levels.

A Swiss study, for example, noted that multilingualism is estimated to contribute 10 percent of Switzerland’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), proving that the language skills of workers open up more markets to Swiss businesses, greatly benefiting the economy as a whole. In Britain, on the other hand, the cost of the country’s stubborn attachment to the English language and unwillingness to significantly invest in learning other languages, has been estimated to be as high as £48bn a year, or a staggering 3.5 percent of GDP.

For businesses, the language skills of their workers – be it a language spoken in a new market they’re expanding to, or English, the global lingua franca – are just as important. In an Economist Intelligence Unit study, quoted in the 2014 EF EPI, nearly 90 percent of managers said that better cross-border communication would improve the bottom line, while another study noted that 79 percent of companies that had invested in the English skills of their workers, had seen an increase in sales.

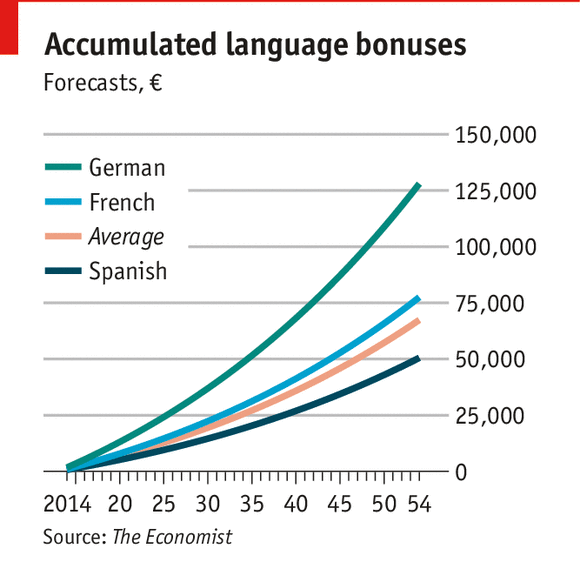

At the individual level, the benefits of bilingualism are a little harder to quantify, mainly because they depend on industry, location and level of employment. A 2010 study in Canada, for example, showed that bilingual workers earned between 3-7 percent more than their monolingual peers. Speaking both of the country’s official languages – English and French – helped people earn more, even if they weren’t required to speak that second language on the job. In the US, studies have shown that speaking a foreign language can increase your salary by (at least) 1,5-3.8 percent, with German skills having the highest value due to their relative scarcity and Germany’s importance to global trade. In India, this premium was even more notable, with those who spoke English earning, on average, 34 percent more per hour.

Bilingual or multilingual managers are also increasingly valued and sought after: Recruiters and industry leaders consider them to be better equipped to manage both global business relationships and teams.

There are clear and very tangible benefits to being bilingual. Although there is limited proof that growing up bilingual gives children a significant cognitive edge, lifelong learning and using a second language regularly does indeed seem to make our brains more nimble and resilient. The economic benefits, moreover, can be substantial. Speaking more languages also makes us more open-minded and helps us feel more connected to other cultures and to the world. Who knows – bilingualism might even foster peace and understanding at a global level. If that’s not a good reason to learn another language, I don’t know what is.

src

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.ef.com/blog/language/bilingual-is-better/

Good article. I support your mindset that bilingual or multilingual life is easier. When you speak first language it's easy. With a second one you have to learn how to turn a switch in your head. You don't only listen and speak but also think in a second language. Or in a third for that matter. I live in a small country on a crossing of 4 linguistic groups. Slavic, Romance, Germanic and Finno-Ugric. We have our own official language, quite hard to learn, ranking in the top 25. Because wherever you live you have a border closer than 50 km away - so most of the population is bilingual. And most of the population also speaks fairly mid english.

Not that we asked for it, but for a bit more than 2 mio people this is quite an achievement :)

Haa, I gave you quite a few information. Would you know which country I am talking about?