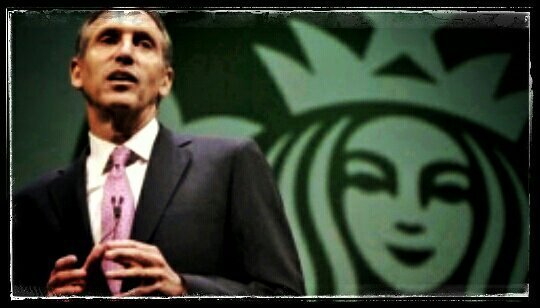

Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz was forced to resign last April because segments of the population used their power of consumer choice to express opposition to the liberal social and political agenda he advocated, and caused the company’s profits to decline in successive financial quarters.

Schultz had declared his (and Starbucks’) support for Gay marriage and vowed to hire 10,000 refugees in response to the anti-immigration rhetoric of the Far Right. Polls showed that these positions had weakened the Starbucks brand, and the resulting downturn in profits forced Schultz out. This provides us with a very clear example of the demoratisation of corporate influence, and there are a number of lessons to be learned from it.

In this case, political conservatives mobilised against the liberal stances Schultz had taken, and succeeded in punishing Starbucks sufficiently to force a change. This is interesting because the demographics of political conservatives are not generally the demographics of Starbucks’ core customer base. Undoubtedly, Schultz felt confident to throw his company’s weight behind Gay marriage because he felt that this stance would be welcomed by Starbucks’ customers, and that the only people who would be alienated by it are not really buying Spice Pumpkin Lattes anyway. The same goes for his announcement to hire refugees. Enough Starbucks paper cups were seen being held by Trump protesters to lull Schultz into a false sense of security.

But his consumer constituency failed him.

The boycott by conservatives was not offset by increased support from Starbucks core customers. Schultz’s public political stances were not rewarded by pro-immigration and pro-Gay marriage supporters buying more Frappuccinos; thus the Far Right was able to dent the company’s profitability , even though they are not regarded as Starbucks’ vital market.

Under Starbucks’ new management, you can expect the company to be far less political. The lesson they will have learned is that it does not pay to take political stands. The lesson they should learn, however, is that it does not pay to take political stands which do not reflect the values of the population, and that it does pay to take stands that do. And here, responsibility is upon people to become consumer activists. If liberals had considered it an act of political support to buy coffee from Starbucks, and to reward and encourage Schultz for the stances he had taken, they could have easily nullified the impact of the boycott by conservatives.

It does not take an enormous level of participation to negatively impact a company’s profit margin; that is a useful lesson for us. And it is supremely important for activists to intensify their consumer support for a company when they take a positive political stance; that is another important lesson.

The Far Right treated Starbucks as a political entity. They mobilised, and they won. Market democracy works like political democracy; those who participate get representation, those who do not participate, don’t. A minority of Starbucks’ consumer constituency overthrew Howard Schultz because the majority did not “go to the polls”.( )

)

Military conflict appears very different depending upon your vantage point. How you perceive the battlefield when you are on it will be radically different from the way it looks from, say, Washington, and more different still, from Wall Street. Seeing as how our lands are quite often battlefields, we tend to view these conflicts from the single vantage point on the ground.

From here, of course, the imperative is to engage the invading or aggressive military forces. It is to upgrade our weapons capabilities and degrade the capabilities of the enemy. We deal on a block by block, district by district basis. Victory, indeed survival, requires us to be this way. From the ground, the urgent thing is how to prevent an air strike, how to evade it, and if possible, how to bring down a fighter jet. From this vantage point, the concerns are immediate, tactical for short term wins; planning ambushes, striking checkpoints and convoys, etc. The medium to long term planning is also within the framework of battlefield immediacy; can we develop methods for scrambling the signals of drones? Can we manufacture our own weapons, and so on. If enough small victories are achieved, perhaps they will build the final triumph.

From Washington, as you might expect, the view is very different. Weapons and support for you and for your opponent are two valves, side by side, opened and shut with careful synchronicity to maintain a balance of power on the battlefield, until an atmosphere is created that is conducive for the inevitable political solution to be crafted, proposed, and imposed by politicians from each government involved in the conflict. This process is expensive, of course, and these expenses will be explained as vital to the national security interests of the country when they submit their budget requests to Congress. Congress will concur with that assessment, not because the expenses are vital to national security, but because they entered congress, in part, with the considerable financial support of the aerospace and defense industry.

From Wall Street, like from the ground on the battlefield, every downed fighter jet, every disabled tank, every fired missile (whether it hits its target or not), is celebrated. Unlike on the battlefield, however, every bombed hospital, every demolished bridge, every devastated city, no matter which side of the conflict is affected by it, is also celebrated. Where we see rubble, they see a market. Where we see a loss for the enemy when his weapons are destroyed, they see a guaranteed sale of new merchandise. Regardless of which side in the war is momentarily prevailing, from Wall Street, they see the victory of a climbing share price. Every major sector of the American economy is connected to military production; technology, construction, telecommunications, aerospace, the automotive industry, and obviously defense and weapons; everything. Through every major financial crisis of the last two decades, war based industries have enjoyed uninterrupted prosperity.

The combined political power of these industries is unequaled in the United States. Their economic power dwarfs that of many small countries. And, when we talk about companies, we are not talking about faceless entities; we are in fact talking about their owners; the corporate shareholders. We are talking about the super rich who organize their wealth in the form of corporations. They finance politicians, essentially hiring them as they would a CEO, and assign them the task of increasing share values for their companies; and they do this through government policy. If they fail to do this, like an unsuccessful CEO, they will be replaced.

Thus, the overwhelming driver of policy is this; to serve the financial interests of the owners of the government. As long as a policy achieves this, that policy will continue. If you are interested in changing that policy, there is only one way: you have to ensure that it fails to achieve its aim. And you have to understand its aim, not from the vantage point on the ground, not from the vantage point of the policy’s victims, but from the vantage point of those who benefit from it.