So, I guess it has been a little while since I last posted, but we can thank that lovely flu virus going around for that. So here is my (hopefully) long-awaited part 6. I do hope it lives up to your expectations.

I have been asked the question as to whether dinosaurs were warm blooded or cold blooded. Identifying an animal as warm or cold-blooded also provides a window to their behavior. Cold-blooded animals are lethargic until warmed by the sun and may be inactive at night. Warm-blooded animals have more opportunity for nocturnal activities.

Microscopic study of dinosaur bone (histology) provides important clues to questions of vertebrate metabolic rate (Chinsamy 1993). Interdisciplinary research is critical to the advancement of science. While the warm-blooded/cold-blooded question is intriguing and probably amenable to scientific solution, it may not matter; with sauropods who were so big (so much mass compared to amount of exposed skin) that they did not lose or gain significant amounts of heat over the course of a day, a condition called inertial homeothermy (Carter 1967).

Picturing sauropods with heads significantly elevated above their bodies stimulated cardiovascular physiologists to question the efficiency that blood could reach the brain (Choy and Altman 1992).

The stress of pumping blood up 20 feet (6 meters) from the level of the heart could pose a problem. Whether the sauropod chest could hold a heart of sufficient size to accomplish this was questioned (Choy and Altman 1992).

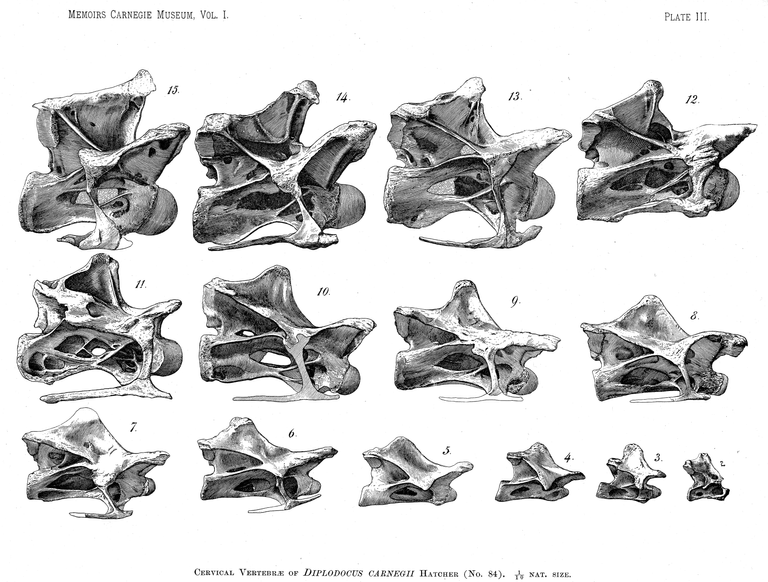

Examination of Diplodocus and Apatosaurus cervical vertebrae reveals large open paravertebral regions (pleurocoels).

These areas are hypothesized to contain "secondary hearts" which provide additional propulsion of blood to overcome gravity. (Choy and Altman 1992).

Though an interesting speculation, new studies provide another perspective. Apatosaurus and Diplodocus did not have necks oriented vertically in prone posture; rather they normally carried their necks horizontally (Berman and Rothschild 2005). The open spaces (pleurocoels) may have contained air sacs, providing a broad but light neck.

Photo by Vladimir Nikolov

Photo by Vladimir Nikolov

References:

Chinsamy, A. 1993. Bone histology and growth trajectory of the prosauropod dinosaur Massospondylus carinatus (Owen). in The Sauropods: Evolution and Paleobiology. Rogers, K.C., and Wilson, J. A., eds. University of California Press, Berkeley, pp. 285-304.

Choy, D.S . and Altman, P.1992 The cardiovascular system of Barosaurus: an educated guess. Lancet 340:534-536

Berman, D. S. and Rothschild B. M. 2005. neck posture of sauropods determined using radiological imaging to reveal three-dimensional structure of cervical vertebrae. in Thunder Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs.

Hatcher, John Bell 1901. Diplodocus: its osteology, taxonomy and probable habits, with a restoration of the skeleton. memoirs of the Carnegie Museum 1:1-63.

Part 7: Talk about a stiff neck.......

Hey @dinodoc! Yes, I remember seeing dinosaur drawings in school books depicting giraffe-like posturing on impossibly tall creatures. You'd think they would drag their tails in the dirt constantly, but I remember from one of your earlier posts that they were carried horizontally. Great learning here!

Thanks for following

My pleasure, Doc! Great stuff here!

@originalworks