When people thinking of underwater archaeology, I fear most see Indiana Jones on scuba. Don't get me wrong, there are a lot of exciting experiences that have come along with my occupation. Still, there are times when it is not glamorous at all. In fact, there are times when I wish I was in a different line of work. When those thoughts come up, I have to remember all the great things that come along as well.

The Job

One of the strangest underwater contracts I worked involved diving in the Houston Ship Channel. For anyone that has visited the upper Texas coast, you surely know the water there is chocolate brown presenting little to no visibility when you duck your head under. For anyone who has not experienced this type of environment, go buy a scuba mask, spray paint the inside of the mask black so no light gets inside, then put it on and jump in a pool. That will give you some idea of what it is like to dive along the upper Texas coast. This was not my first experience diving in Texas waters mind you. I had been diving along the Texas coast for years on various assignments. Diving in "Black Water" has never been at the top of my list. It can present many emotions similar to claustrophobia which is odd since you are not in a confined space. It can just feel confining since you can't see anything.

On this particular assignment, my team was hired to survey the Houston Ship Channel prior to Port of Houston's plan to dredge part of the channel. This dredging was to give more depth in a specific part of the Channel for the large ships that use it to enter the Port of Houston. Our job was to satisfy part of the Port of Houston's legal obligation to the State of Texas by certifying no archaeological remains would be damaged or destroyed by their planned dredging activities.

Now, imagine what I wrote above about buying a mask, spray painting it black, and jumping in a pool. Imagine you did that and you were not in a pool, but in the Ocean at depths of 25-45 feet. Now imagine there were huge ships going by every hour. That will give you some semblance of the environment we were working in, plus there could be sharks.

As with many of these projects, on paper, it looked fairly straightforward. We would spend a week performing a remote-sensing survey with a marine magnetometer. Think of a metal detector that trails behind a boat over a predefined area. As metal, specifically iron, is identified it is plotted on a map for diver identification. Once all potential targets are plotted, based on the remote-sensing data, we would move into the next phase of the job, diving investigation.

Dive Gear

I am sure it is hard to consider how someone in blackwater with no ability to see can do any kind of investigation, but that was the job. So, here is the setup.

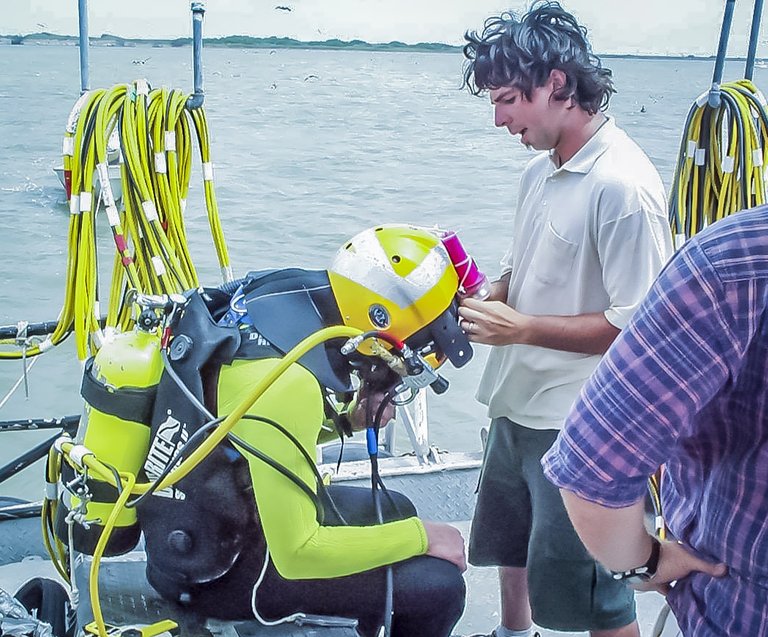

Diving was conducted using surface supplied air. That means an air compressor onboard the dive boat pumped air down to the diver via an umbilical hose. Air is gathered from the air around the boat, filtered, and then sent down to the diver's dive helmet. The diving helmet is a Kirby Morgan that attaches to a dive collar around the diver's neck. Inside the dive collar is a piece of neoprene (called a neck jam) that act like a gasket after the diver squeezes their head through. Once the diver pushes their head through the neck jam, the helmet is put on the diver's head and locked down to the dive collar. The neoprene is supposed to keep the water out of the helmet like a jam. I say supposed to because there always seems to be water pooling around my chin inside the helmet. If the helmet did flood, there are ways to control the amount of air entering the helmet which can be turned up to force the water out. Other equipment on the helmet includes lights which were a joke because they did not help at all.

To prevent strain on the umbilical, divers are also connected to the support boat via a tether. The tether is stronger than the umbilical and should take all of the strain that might occur. The last line needed is the wire for diver to surface communication. All 3 of these lines run from the dive boat down to the diver. They are all wrapped together at various points to keep them from getting tangled and to give the diver as much mobility as possible. As the diver enters the water and moves around, a "tender" has to handle the lines by letting them out or taking them in as the diver needs.

Other equipment that is needed includes a harness, which might include flotation, wetsuit or overalls, glove, neoprene boots, weights (a lot of weight), and any and all tools needed for the work at hand.

The last, but very important piece of equipment needed was the diver's bailout tank. The bailout tank was smaller than a normal scuba tank. This was a 45 cu. ft. tank that was strapped to the diver back by being attached to the diver's harness. Then tank had a regulator hose that ran from the tank and into an air bloc on the helmet. This would allow the diver to use the air from the tank just as they would use the air from the compressor onboard the support boat. The bailout was used if there were an emergency and air was not coming down to the diver by way of the umbilical. The diver could reach behind their head and turn the tank on and air would flow to the dive helmet. If a diver ever turned on their bailout, the dive was over immediately. That tank of air was strictly to get the diver back to the boat. On the surface, prior to entry, the bailout tank was turned on to pressurize the hose to the helmet. Once tested, the tank was turned off without exhausting the air in the hose. This way if the diver needed air, as soon as the tank was turned on, air would flow. The tank was not left on because it might leak during the dive. If that were to happen and the diver didn't notice, the tank might run dry during the dive and then not be available in case of an emergency. No Bueno…

There is nothing more alarming than to have the support team radio down to you with the clear instructions to "TURN ON YOUR BAILOUT NOW!" That meant there was a problem. Once when that happened to me I asked what the problem was and the support team kept repeating to turn on my bailout. After I confirmed air was flowing, I again asked about the problem. My support team laughed and said, "Sorry, we forgot to top off the compressor earlier and it ran out of gas." Just one more thing to worry about when diving in blackwater.

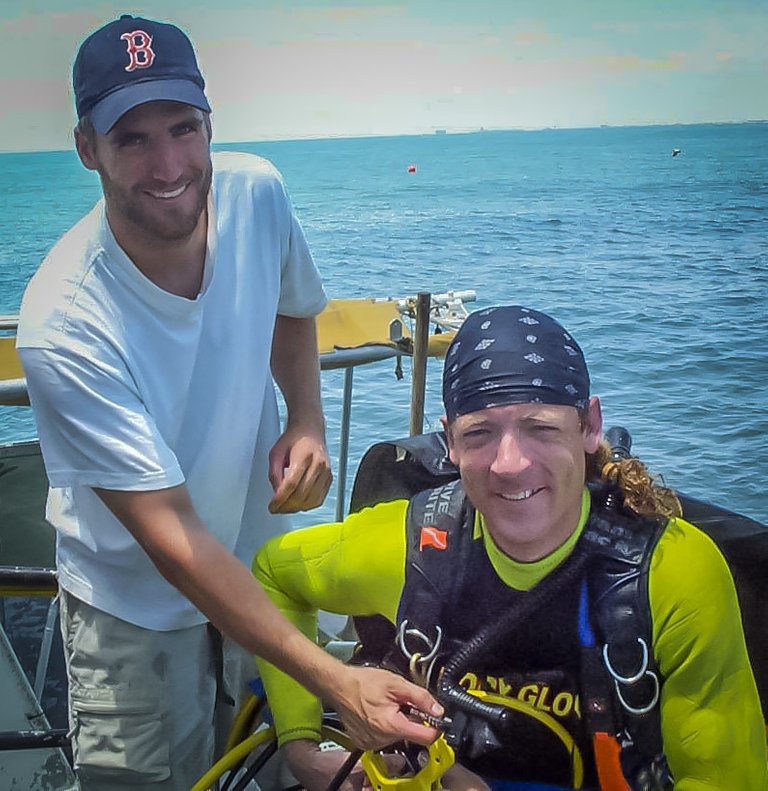

To get suited up on the dive boat, there was a support team that helped the diver with their equipment. This was to make sure none of their hoses or lines got trapped or tangled and so everything was accounted for and tested before entering the water. The radio operator was the last person to perform their check. Once all the gear is on and tested, and right before the diver hits the water, the radio operator would test the comms to make sure the diver could hear them and they could hear the diver. Once everyone gave their final "OK," especially the diver and Dive Safety Officer, the dive could begin. At that, the diver could lower themselves down the dive ladder and into the water as the tender took up their lines and trailed them out as needed.

Once the diver's head went below the surface, all communication was handled by the radio operator. There is another form of communication but less used, really, it was only used if the comms went out. That was communication by pulling on the tether. Depending on how a tender pulled and in what direction they pulled they could communicate to the diver is needed. Mostly, communication was handled by the radio operator. Still, the responsibilities of the tender are huge. They need to make sure they are managing the lines running to the diver efficiently and responsibly. This is especially true if there is an emergency. During each dive, you have the radio operator who is communicating with the diver, the tender who is watching the hoses to make sure the diver can move freely, and the Dive Safety Officer watching everything.

The Dive

As mentioned, the dives in the Houston Ship Channel were a little unusual because we were diving in an active ship channel. There were going to be big tankers going by every hour. For safety, we felt it best to pull divers out of the water each time a tanker approached. Getting a diver back to the boat before each hour took time so the diver's time on target would definitely be limited which we started to realize would extend the overall time needed to survey all targets.

To get to each target, divers who could not see anything underwater had to be guided to the target by the topside support team. Up top, the team had maps showing the position of each target, they had a DGPS and knew where we were located. We also had a sonar underwater that used sound waves to create a picture of the seafloor. The support team could watch the diver's bubbles and the direction of the trailing umbilical, to help guide the diver to where they were supposed to go. The diver, on the other hand, had no idea where they were and which direction they were headed. They also couldn't tell if they were about to step off the side of the channel and drop into the channel which was always a bit of a surprise. It could take some time, but eventually, the diver would get to where they needed to go.

Now, because the targets were found using a magnetometer and not a side scan sonar, just because the diver was on top of a target didn't mean the target was on the surface of the seafloor. We generally already knew this by way of the sonar we used to guide the diver to each target. If this was true, we knew the target was buried under the mudline. If the target was on the surface of the seafloor, chances are it was more modern. Any historical remains (anything over 50 years old) would have long been buried, but we still had to confirm each target.

If the object was above the mudline, the diver would be directed to it by the support team. These targets were much easier to find because they could actually knock into it. In some cases, this was a large pipe, probably part of a gas line or oil pipe that might have fallen off a boat or had been used for a gas head or oil head and somehow ended up where it did. In other cases, it might be a 55 gal barrels or other debris. In one particular case, I actually walked into the side of a shrimp boat that had sunk somewhere in the area but had moved around underwater finally landed on the side of the Houston Ship Channel we were surveying. As I was being guided to the target, I literally ran into it. This was a fairly large boat and I walked into it underwater. This can be very startling, to say the least. It took a quite a while to figure out what it was just by touch. I would feel around and then report back to the support team where someone up top would try and draw what I was trying to describe without me ever being able to see the object I was describing. It made us laugh all the time as everyone involved throughout what they thought it was.

Targets that were buried were much more difficult to identify because we would need to dig. To get under the seafloor, we used a water probe with a 5-6 ft, hollow 1-in pipe. On one end of the pipe was open, that was the end the diver pointed toward the seafloor and the other end was attached to a hose that ran up to the support vessel and was attached to a water pump. Once the diver was ready, they would call up to the support team to turn the water pump on. This sent water rushing down through the hose into the pipe. The diver would then use the water probe to push into the seafloor. The blast of water would move sediment aside and allow the pipe to cut through the mud like butter. If the diver was not paying attention, however, the jolt of water rushing through the pipe could ripe the pipe out of their hands. Then, the diver would have to find it in the dark.

To use the water probe, divers would push the pipe into the mud and then back out over and over until they hit something. Once they did, they would continue with the water probe trying to find the extents of the object. Almost like they were outlining the perimeter of the object. They would also try to open up a hole over the object big enough to stick their hand down into to feel around to determine the size of it. This process could take many dives in some cases to dig out an area big enough to get an idea of its size to be able to work with the support team in identifying what it might be.

So, having to pull the diver out each hour to let the tanker go by was making the process really drag out.

Starting day 3, not having made much progress on day 1 and 2, I decided to try something different. During the night, I had wondered what would happen if the diver was not recalled as the tanker went by. Could a diver say in position, allow the tank to churn by and then get back to work. If this were possible, it would say a tremendous amount of time and allow us to get back on schedule. So, as I was suiting up for my next dive, I told the Dive Safety Officer that I wanted to stay in the water as the next tanker came by to see what would happen. At first, he laughed because he didn't think I was serious. After a few moments, he realized I was and asked if I was sure. We all realized the time we were losing each dive and time is money after all. We also didn't really know if there was anything really to be concerned about. I would still be tethered to the boat. I also told them I would push the water probe into the seafloor as deep as I could and would hang on to it if needed. It took some convincing but after a bit, the DSO and everyone onboard agreed to let me try. They were all as eager as I to make some progress and we knew if we had to keep pulling divers out of every hour, we would all have to stay out on the site many more days before we would finish and would be able to get back home.

As I lowered myself down the dive ladder and into the water, I was trying to imagine what it would be like staying in the water as the tanker passed. I knew it would be loud but I didn't really know what else might happen. Once underwater, the radio operator called and directed me back to the target. I had the water probe with me and I was going to continue work from the day before. We still needed to find the object that had created the anomaly. Once in position, I continued the investigation. About 30 minutes later, I could hear the faint sound that signaled the approach of the tanker. This was the sound of the propeller churning through the water. Normally, this would have also been the signal for me to head back to the boat. This time, however, I was going to stay down. I let the support team know I heard the approach of the tanker and they confirmed they had a visual on the ship as well. I was told to position myself with the water probe as we discussed. Once in position, I called up for the support team to turn off the water pump. With the noise of the water pump and water coming down the pipe gone, I could hear the sound of the propeller getting louder as the tanker grew closer. Propellers on oil tankers are big. Some are as big as 18 feet across. I am not sure how big the one on the tanker bearing down on me was but it sounded huge. The sound it made grew louder and louder and louder. The sound is not what bothered me, however. As I waited, I started to notice the visibility getting better. I could actually see. At first, it was just a couple of inches and then a couple of feet. As I looked around in amazement, it took a minute or two before I realized what was happening. I also started to notice the current was picking up. It was mild at first but it got stronger and then stronger and then stronger. That is when I realized, the tanker was coming right by me. The sound was deafening and I was beginning to get "pulled" out toward the ship. I then realized the ship was pushing a huge volume of water out in front of its bow as it cut through the water. That push of water was creating a current underwater and pulling me out toward the ship. When I made this connection, I grabbed hold of the water probe for dear life. I also radio up what was happening and told them to make sure the tether held fast. They asked if they should pull me in but it was too late for that. I had to see this through.

As the current continued to increase, my feet actually left the bottom and started to move in the direction of the ship. I was now more of a flag blowing in the wind with my feet pointed toward the ship. All I could do was laugh. It was like a ride at an amusement park. I just had to hang on. I then noticed that the pipe was coming loose from the seafloor. I had buried it as deep as I could but apparently, it was not deep enough. The pipe was definitely coming loose, but I just continued to hang on as the ship passed. Slowly the current started to decreased and my feet returned to the seafloor.

Just as I was catching my breath, I let the dive boat know I was alright. But, as soon as I told them everything was OK, I noticed the visibility was starting to return to the poor condition it was before the ship passed. I didn't think much of it until I realized much quicker this time that the current was picking up again but going in the opposite direction. I reached out for the pipe but could no longer see or feel it and the current pushed me out in the opposite direction. The water the tanker pushed out in front of its bow was now returning. It was moving just as fast as it had left. I had no idea which direction I was going but I was going fast. Really fast. Eventually, I hit the end of my tether with a jolt as water continued to rush by my body. There I just grabbed hold of my umbilical and tether and blew like a flag in the current. This lasted a minute or two before it too passed.

And Then…

Ok, so that was a bad idea. After all of that, I just sat down on the seafloor, in the pitch darkness thinking about what had just happened. Then, out of the darkness, I heard the support team call over the radio. "Hey, just so you know there is something on the radar and it is as big as you and it is moving. You might want to get out of there." There were only two things it could be, a dolphin or a shark. I was hoping for dolphin but I wasn't going to wait and find out, it was time to go…