G'day team,

Finally! As promised I've finished writing up this piece on the difficulty of combatting Antibiotic Resistance. In my first article I covered the basics of how antibiotic resistance develops, and why it's such a threat. Today I'll be having a closer look (issue-by-issue) at some of the big issues that are holding doctors, scientists and other health professionals back in the fight against so-called 'Superbugs'. Some of the issues are listed below:

- Creating new antibiotics is hard

- Economic incentive to create new antibiotics is low

- Resistance develops fast

- Politicians don't care

- Problems with antibiotic stewardship

- Animal husbandry contributes to the problem

So, let's get into it!

Creating Antibiotic is Hard

Creating any drug is hard work and it can take a decade or longer to get a drug from concept to the public. But beyond this problem of red tape and regulation, antibiotic drugs face another problem... we're running out of ideas!

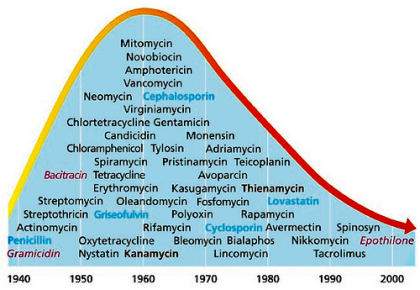

Image source

This is a great chart which shows when we began using the specific classes of antibiotics that we use today, and as you can see new drug production in the last thirty years has dwindled. In fact there's been a 90% decline in FDA approvals for new antibiotics in the last 30 years.

In the past, we relied on compounds that were produced naturally by fungi, as a method of defending themselves from bacterial invasions. But, as you can imagine, as soon as Penicillin was firt isloated from fungi people pretty quicky got smart and started raiding the animal kingdom for natural antibiotics which they could isolate and produce artificially. Natural compounds might even be modified by scientists to increase absorbability in the gut or the time they last in circulation, but the basis of these compounds was found in nature. Now we've plucked all these low-hanging-fruit, all the antibiotics that could be easily identified using this method have been!

So where do we move now? Well, scientists have some ideas, but most of them have been a little harder to come up with than our heritage antibiotics.

Let's take Teixobactin, for example, one of only two novel agents in the last 20 years. Teixobactin is a new antibiotic discovered using a device called iChip which is essentially a tiny prison/ fight camp for bacteria in a capsule. The idea is you bury this capsule and let the bacteria/ fungi in it battle it out for a while, when you dig it up again you screen these bacteria for any new compounds they may have developed in order to stay alive during their imprisonment. Now the antibiotic is promising and even has a unique mechanism of action, quite separate from the traditional methods used by old antibitotics. Yay!... sounds great doesn't it. Well it is, but this was all found in 2015. The problem with antibiotics is that from lab to hospital development (even with red-tape waived) takes a long time! And who is going to fund this sort of long-term research? Well as we'll see, probably not pharmaceutical companies.

Economic incentive to create new antibiotics is low

There will be a cohort of people who get to this point in the article and start getting really excited at the prospect of blaming everything on 'Big Pharma'... If you are one of those people please stop reading, go to your local university and take an undergraduate course in sience. During this course you can learn the difference between a conspiracy theory and the real-life constraints of medicines and other medical agents. Now!

When penicillin came out it was three things... A miracle, cheap and effective. Now it is just cheap. And this is a big problem. The medical market adjusted to the idea of cheap antibiotics, and for decades this status quo was kept, as pharmaceutical companies were able to 'pick the low-hanging fruit' and discover new agents with an investment of minimal time or effort. It's probably important to mention that in this day and age the red tape and beurocracy that's behind getting a drug approved wasn't quite the nightmare it was today either.

So we have a market which expects cheap antibiotics, and pharmaceutical agencies which were happy to comply with this for a while. Time to get a little technical...

When a new drug is developed it is used as a sort of 'secret weapon' or a last resort. Say we produce a new drug called KillBugs. Now KillBugs is 100% effective at killing all bacteria, and there are no resistant strains know. But if we start using KillBugs in every patient that comes through the hospital doors, we'll just be promoting the development of antibiotic resistance, and all of a sudden KillBugs is no longer our secret weapon. Now KillBugs is useless. This is why we keep KillBugs as a last resort. We use it only when all else has failed, which means we don't use it often, and so we can be quite sure no resistant strains will pop up.

But we've created a problem!

This means we're not buying much KillBugs... maybe we use it once a week, versus a more common antibiotic (say, ampicillin) which we're using a thousand times a week. This is good for us but bad for the pharmaceutical companies. Even if they make the price of KillBugs ten times higher than that of ampicillin ($10 vs $1) they're still not making much. This means that they're going to find it hard to cover all the costs of developing the drug in the first place.

Now let's look at this from a pharmaceutical companies perspective. We have this new compound we've found called SuperKill which could make a great antibiotic. But it's going to take us ten years and $100 million (average range is actually between $85 and 137), and if the drug passes all trial (which it probably wont) at the end of this time every hospital in the world will be stoked because we'll have given them a secret weapon and in exchange they'll but a few vials. And then not use them unless they are pretty much forced to. All that funding and effort for nothing! Well as the CEO of this pharmaceutical company I'm just going to pick up an existing antibiotic which I know works, and throw some carbon chains on the side to see what happens. It's cheap and if I'm lucky I'll be able to patent a new drug which works exactly like an old one does, but which my marketing team can jazz up and sell privately for twenty times the price.

Now there are ways to adress this, and without getting into too much detail they involve public-private partnerships, fast-tracking of antibiotic drugs through approvals, giving tax credits and allowing market exclusivity for new drugs (free of generic drug competition).

But let's say we've gotten through all this. SuperKill was developed in just 7 years and it took us only $50 million dollars, we're stoked and the government is helping pay the costs because hospitals are using it responsibly and therefor not using it much.... but then!

Resistance Develops Fast

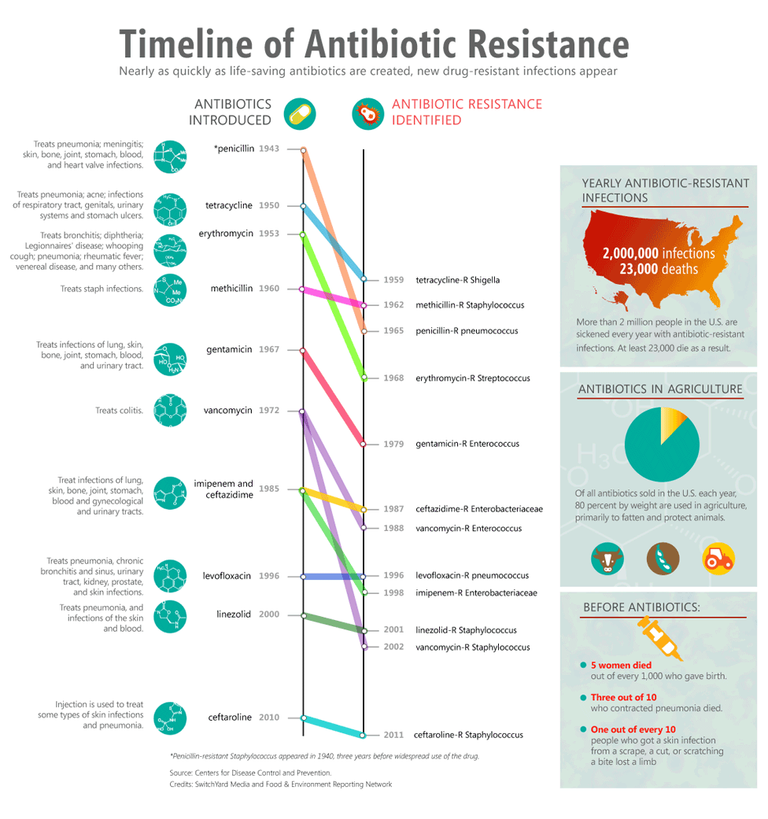

Let's take a look at the wonder drug that was 'Vancomycin'. Vancomycin was fast-tracked for approval in 1958 due to the up-rise of Penicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureaus and it was expected to do great things. In trials it was quite apparent that staphylococci couldn't easily develop resistance. The first problem was the drug itself, despite being very effective it was toxic and bad at reaching the skin (where most Staph Aureus is found). In 1986 Enterococcus strains resistance to vancomycin emerged and in 1987 was widely accepted. Now almost thirty years of a drug without resistance seems pretty good doesn't it! But this is taking in to account a drug that was barely used globally till the early 1980s. And Vancomycin is one of the best drugs we have. Look at the chart below and how quickly antibiotic resistance develops for most drugs.

Even if every drug we develop now has a 30-year life-span, that means we have to develop a new antibiotic for every class of bacteria for thiry years... forever. Not exactly a promising prospect, and not something the pharmaceutical companies are over-the-moon about. Maybe the government will help? I wouldn't bet on it...

Politicians don't care

Now this shouldn't come as a surprise but the road to overcoming antibiotic resistance isn't going to be a cheap one, in fact it'd probably be much cheaper if it was paved with actual money. But with no economic incentive for pharmaceutical companies we turn to phillanthropy and the government, both 'the peoples money'.

Funnily enough people, being emotional beings, are far more interested in pouring money into cancer research for children, new drugs for chronic heart disease or ground-breaking research into the next cure for diabetes. Now these are all worthy areas, but at the end of the day antibiotic resistance is left in the background. It's simply not sexy enough. As a result funding for research is poor, coordination of international efforts to control antibiotics are poor and public awareness is poor.

Problems with antibiotic stewardship

Now it's time to get boring! Antibiotic stewardship... it's the practice of controling when and how antibiotics are used to treat infections caused by what organisms in what parts of the body in what populations of people... if you're not yawning then honestly you're not human. By minimizing unnecisary antibiotic use we minimize the incidents of antibiotic resistance developing.

None the less. Antibiotic stewardship remains one of the most powerful weapons we have in the war against anibiotic resistance, but these efforts have a whole slew of their own issues too.

Poor funding

Just like the rest of the antibiotic resistance battle, the area simply isn't sexy.

Poor international coordination

There is no single central and recognise authority on antimicrobial stewardship, this means there is no one to whome everyone can turn and no who can act as a reservoir for funding and re-distribute money for research and other incentives fairly and globaly.

Difficult to conduct studies, with small cohorts

Much of the research into antimicrobial stewardship relies on small cohorts, as multi-center studies are difficult to coordinate.

Outcomes are hard to identify

How do we figure out if we're actually being succesful? Is it the number of patient who die in a week, or a month? Is it the time till a patient can go home, or how they feel after a week? Is it the cost of their total admission, or is it the total incidents of antimicrobial resistance developing? It's important to remember that antimicrobial stewardship needs to BOTH improve patient outcomes AND decrease the risk of antimicrobial resistance developing. This is no easy task.

The third world is left behind

You're in a small clinic in rural Nepal, a patient comes in with a sick child that has a fever and you can't identify why (with no investiations available), you have two antibiotics available. Do you give the weak one and hope for the best, or give the strong one? There really is no choice here. And this is the problem faced in many developing nations. Not only do many of these healthcare fascilities not have any guidelines on antimicrobial stewardship, they simply may not have the alternative options for treatment that we have in the first world. Abstaining from antibiotic use may be an option for an ear infection in a big hospital where a child will go home to a hygienic house, but the same may not be said in a rural setting where they'll go home to a shack on the side of the road.

Animal husbandry contributes to the problem

Eighty percent of the antibiotics used in the USA and Australia are used in livestock. Europe has banned this practice... in 2006, but to this day have only managed to cut their numbers by 60%. The problem is animals do need antibiotics, but they are often used in all animals, not just the stick ones. This just gives bacteria more chances to develop resistance and spread to human populations, generally through those who are in close contact with the animals themselves.

That's it

Well done, that's it! It's not a comprehensive overview of all the problems facing this field, but you'll at least have an appreciation for the difficulties that are faced in this field. Moving forward we need to see more government support internationally, more enthused researchers and, honestly, a lucky break in our uphill struggle to find new antibiotic classes.

Thanks for reading!

-tfc

Resources

- We need new antibiotics to beat superbugs, but why are they so hard to find?

- New class of antibiotics discovered – and why there may be more to come

- A new antibiotic kills pathogens without detectable resistance

- A Comparative Study on the Cost of New Antibiotics and Drugs of Other Therapeutic Categories

- Jim O-Neill. (2016). Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance.

- Ferri, M., Ranucci, E., Romagnoli, P. and Giaccone, V. (2015). Antimicrobial resistance: A global emerging threat to public health systems. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 57(13), pp.2857-2876.

- Luepke, K., Suda, K., Boucher, H., Russo, R., Bonney, M., Hunt, T. and Mohr, J. (2016). Past, Present, and Future of Antibacterial Economics: Increasing Bacterial Resistance, Limited Antibiotic Pipeline, and Societal Implications. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy, 37(1), pp.71-84.

- Howard, P., Pulcini, C., Levy Hara, G., West, R., Gould, I., Harbarth, S. and Nathwani, D. (2014). An international cross-sectional survey of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in hospitals. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy.

- Schuts, E., Hulscher, M., Mouton, J., Verduin, C., Stuart, J., Overdiek, H., van der Linden, P., Natsch, S., Hertogh, C., Wolfs, T., Schouten, J., Kullberg, B. and Prins, J. (2016). Current evidence on hospital antimicrobial stewardship objectives: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 16(7), pp.847-856.

- Tiong, J., Loo, J. and Mai, C. (2016). Global Antimicrobial Stewardship: A Closer Look at the Formidable Implementation Challenges. Frontiers in Microbiology, 7.

- Aryee, A. and Price, N. (2015). Antimicrobial stewardship - can we afford to do without it?. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 79(2), pp.173-181.

- Leung, E., Weil, D., Raviglione, M. and Nakatani, H. (2011). The WHO policy package to combat antimicrobial resistance. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 89(5), pp.390-392.

- Anderson, D., Jenkins, T., Evans, S., Harris, A., Weinstein, R., Tamma, P., Han, J., Banerjee, R., Patel, R., Zaoutis, T. and Lautenbach, E. (2017). The Role of Stewardship in Addressing Antibacterial Resistance: Stewardship and Infection Control Committee of the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 64(suppl_1), pp.S36-S40.

- King, A., Cresswell, K., Coleman, J., Pontefract, S., Slee, A., Williams, R. and Sheikh, A. (2017). Investigating the ways in which health information technology can promote antimicrobial stewardship: a conceptual overview. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 110(8), pp.320-329.

My Recent Posts

Hi, I'm Tom! (My life of medicine, science and fantasy)

Super Bugs - What is antibiotic resistance and how we are fighting it

Hydatidiform Mole – When Pregnancy Goes Wrong

Tags - Top 20 Profitable, Engaging and Popular tags

New Years Resolutions - How to set goals, and achieve them

Great job looking at this issue from so many different angles. At this point, I think only a major outbreak with no effective treatment will spur significant antibiotic development.

I agree. A lot of sources are expecting that that big outbreak will come from China. With highly populated cities, poor control over antibiotic use, insufficient medical centers and a lot of travel coming in and out it's a bit of a hot pot. Though to be fair China has been stepping up their game on global health recently, their new One Brick, One Road initiative is just insane in scale and is hitting a lot of good chords. Especially at a time when the US is pulling back from a lot of international health obligations and the world is looking for a new leader.

Awesome summary of the whole tragic situation. Thx!

You make me want to power up just so I can add more weight to my vote on your article. Excellent quality. I will keep following you!

@originalworks

Thanks heaps man!

Feel free to resteem, if you're comfortable doing that :)

Never crossed my mind! Here you go!

Much appreciated mate!

This is a very a good article. As a Pharmaceutical Microbiologist, I appreciate this post more than an average steemian. I wonder less why there are no upvote . You have my vote

Once he builds his follower base, I reckon he will have more consistent upvoters.

You are correct about that...

Thanks very much. It's always tough to grow reputation on steemit, but I enjoy writing about this anyway so it's no loss :)

I also love publishing. I have most of my articles in peer review journals in the open access. Here on steemit its a different ball game

Great article. As a doctor this is a huge problem that we are seeing more and more on the front lines. It's already at the stage where every bacterial culture I see is resistant to something and multi-drug resistant organisms like ESBLs, VREs are becoming all too common.

As you say antimicrobial stewardship is very important and is a huge part of my job as well as educating the general public. I'm always seeing patients coming in demanding antibiotics for conditions that clearly don't need them. I'm happy to enter into a good chat with them explaing why they don't need antibiotics but it sometimes feels like a losing battle. Often have i seen doctors, just so overwhelmed or without time to waste, give out antibiotics to a demanding patient just so they can move on to the next!

You're 100% right... I'm on a rural placement at the moment (in outback Australia) and our supervising doctors are often (reluctantly) handing out Abs for uncomplicated UTIs

Great article again :) Your analysis on the role of pharmaceutical industries logics is pretty accurate I think. I didn't know about the term "antibiotic stewardship" but this seems like a good way to mitigate current risks.

Maybe you heard about Eligo, it's a french start-up developing CRISPR vectors for targeted bacteria killing. The technology is still far from bedside but it could completely change the field.

I hadn't hear about Eligo, no, seems like a project with a lot of potential.

Antibiotic sewardship really works at the other end of the problem, telling doctors when and how they can use antibiotics so that we prevent the evolution of bacterial resistance. It's very successful but unfortunately not very fun :P

Hi as someone who has struggled with chronic UTI's and bacterial resistance i really appreciate your post. As a physician do you think alternative treatments can help us with this problem? For example I have been able to manage symptoms though drastic dietary changes and I am also seeing a traditional chinese Herbalist, taking probiotics, drinking kambucha, exercising, taking cranberry pills and plenty of water. I am also taking a drug called methanamine prescribed by my urologist. I know most Western doctors will be against alternative treatments but I personally have decided to stop taking antibiotics, and let my immune system recover. I still don't know if I am bacteria free but I can tell you I feel so much better physically. My symptoms are also at this point vary atypical for a UTI.

My next question is if there is any data about correlation with gender. Could lack of political will be related to the fact that this is a problem affecting mostly women? Are men equally affected by antibiotic resistance? I think this is a very important conversation that we need to start having.

I also think necessary to generate more information about what we can do as patients. At this point I only take antibiotics after a urine culture. I never skip a dose and I avoid alcohol at all costs when taking antibiotics. And yet after a week or so the infection comes back. I think we also need more information about how antibiotics affect our bodies (for example digestive and immune system) in order to find real solutions to this problem.

Again thanks for your post!

Alrighty... let's get going!

First, thanks for the response, it's great when people take the time to get involved! You've raised a lot of valid points, so I'll break it down issue by issue!

Thanks again for commenting and sorry for all the spelling mistakes :P

Wow thank you so much for taking the time to reply point by point. My main takeaway is that hopefully I will not die because of this infection. I still wonder about antibiotics and the effect they've had on my body. I had a doctor prescribe a low dose antibiotic for 2 years and I wonder by the logic of bacterial resistance, eventually the bacteria will become resistant to that antibiotic. But anyway my story is very long and frustrating. I have also had my urethra dilated because apparently I do not empty my bladder fully, but these procedures have not been helpful of getting rid of UTI. I just know whatever I am doing now is working and I keep both my urologist and acupuncturist on the loop of things. But when I tell my urologist about my weird symptoms, like headaches and foggines he just looks at me like I am a crazy person. So I still think we need a more holistic understanding of how the body works, and how for examply wiping out all the bacteria in my body through years of antibiotic treatment may have had an effect on my current situation. But that's just my opinion. I will keep persevering and hopefully one day I'll find the antibiotic that works.

I will ask my urologist about Ural, seems like a great option. And you mentioned this "one of the best things to prevent a UTI is the presence of a good native bacteria in the urinary tract to prevent infectious bacteria getting a hold" how can this be improved? Nutrition? Other ways?

This is what I was saying about women getting ignored for some symptoms :( I'm sorry you have to go through this!

2 years low dose antibiotics is a very odd approach... perhaps it had a very narrow spectrum and only affected the infectious bacteria? I wouldn't know but it's a though :P

I don't really know the specifics, that was early on in the process (2012) a doctor at an NYU Urology Center, so I was following orders... that is why now I am more of a rebel and don't trust everything doctors tell me. Ok, I didn't understand that part about women being ignored. Now I totally get it.

Lastly, I know every body is different but I think we need more spaces where we can share succesful treatments for antibiotic resistant infections. I personally have been dealing with this for years, have seen many doctors and, as researcher myself, I have never stopped looking for an answer.

Funding!

Haha, yeah I think every doctor wishes they had a designated unit or space to deal with their problem, but funding is such that we have to rely on generalized hospitals, wards and units to face problems that are very specific in nature.

Some hospitals do have specific infectious disease units which deal with antibiotic-resistant systemic infections, and entire deparments dedicated to sharing information and research on the topic... but again due to the problems outlined above we're not making a great amount of progress. For antibiotic resistance there's a dual issue of logistic AND technical barriers we're just not able to surpass at the moment.

Give me a bit and I'll respond properly :)