EXPOSURE STORY PAGES..

006 007 008

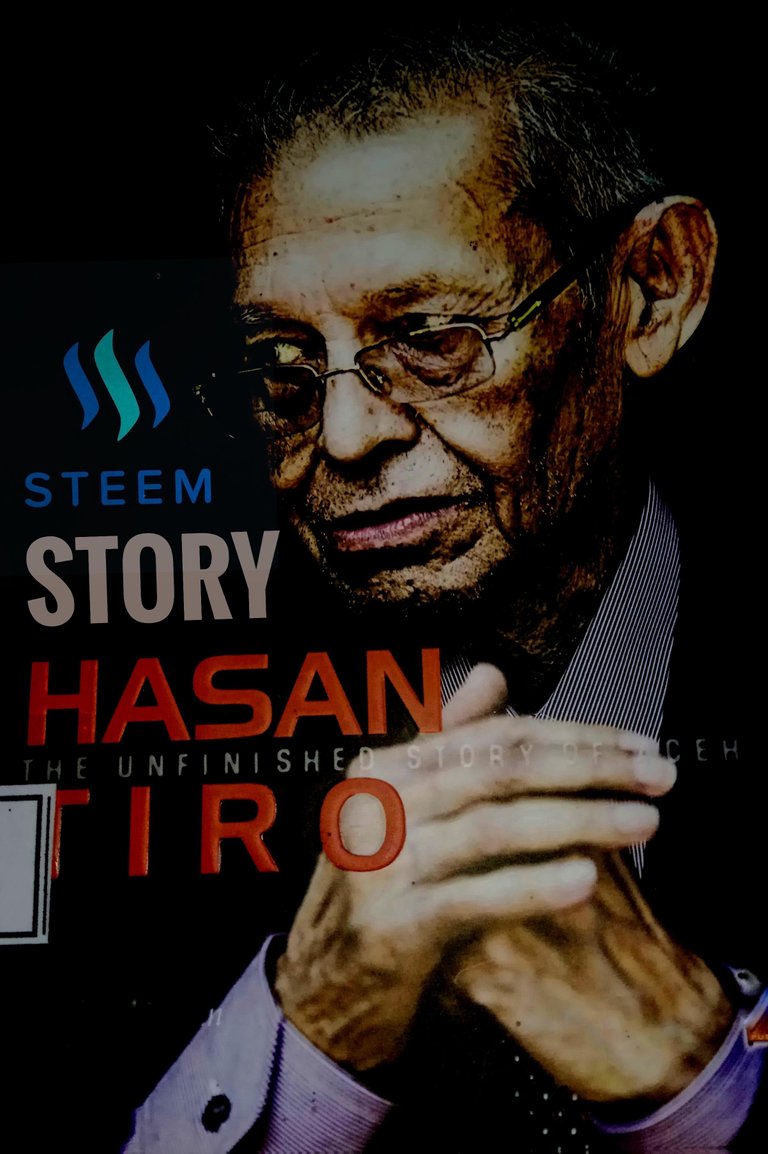

Dissident Hasan Tiro is perhaps the last representative of the restless epoch of the republic seeking the basis of the "common life" of the nation-state we call Indonesia. Born in Tanjong Bungong, Lamlo, Pidie on 19 (another version mentioned 1925 at the age of 19, he had a critical mom of the Indonesian revolution, when the republic was young and was dashed by the Dutch desire to annex the archipelago M Round Conference. with the Indonesian Barisan Pemuda Indonesia (BPI Tanjong Bungong), when he was in critical condition, he decided to assist Deputy Prime Minister Syafruddin Prawiranegara, who had data from Yogyakarta to Aceh.Syafruddin prepared an emergency government in Kutaradja (Banda Aceh) if diplomacy failed in the Netherlands, perhaps Hasan's dedication last year for the republic In 1950 he was awarded a Colombo Plan scholarship to study in the US Hasan l studied economics, politics and law at Columbia University In 1953, Aceh was rocked by the Darul Islam rebellion.Perim reungku Daud Beureueh, Aceh against Jakarta, As he went to school, Hasan was working as an enemy of the Indonesian Embassy t UN, New York. Aceh's reconstruction of Aceh by the republican army in Pulot and Cot Jeumpa, Aceh Be in 1954, angered him. He sent a letter of protest to Prime Minister HASAN TIRO The Unfinished Story of Aceh.

Dissident Hasan Tiro is perhaps the last representative of the restless epoch of the republic seeking the basis of the "common life" of the nation-state we call Indonesia. Born in Tanjong Bungong, Lamlo, Pidie on 19 (another version mentioned 1925 at the age of 19, he had a critical mom of the Indonesian revolution, when the republic was young and was dashed by the Dutch desire to annex the archipelago M Round Conference. with the Indonesian Barisan Pemuda Indonesia (BPI Tanjong Bungong), when he was in critical condition, he decided to assist Deputy Prime Minister Syafruddin Prawiranegara, who had data from Yogyakarta to Aceh.Syafruddin prepared an emergency government in Kutaradja (Banda Aceh) if diplomacy failed in the Netherlands, perhaps Hasan's dedication last year for the republic In 1950 he was awarded a Colombo Plan scholarship to study in the US Hasan l studied economics, politics and law at Columbia University In 1953, Aceh was rocked by the Darul Islam rebellion.Perim reungku Daud Beureueh, Aceh against Jakarta, As he went to school, Hasan was working as an enemy of the Indonesian Embassy t UN, New York. Aceh's reconstruction of Aceh by the republican army in Pulot and Cot Jeumpa, Aceh Be in 1954, angered him. He sent a letter of protest to Prime Minister HASAN TIRO The Unfinished Story of Aceh.  in September Nezar Patria -oo5 experiments 1954. Hasan accused Ali of committing genocide "to the people of Aceh, and asked for Hasa Tiro repeated, but Hasan was angry, himself as a refuse, and he was Hasan or Ambassador of Darul Islam in New York. Since then, Hasan has lived as a dissident, and since then we have known that he became a stern critic of Sukarno.In 1958, Hasan wrote an important book in New York titled Democracy for Indonesia, proposing a federal state for Indonesia, the concept of a united state of the Soekarno version. spicy unified state system, which benefits the great ethnic Javanese, and only supports what he calls "primitive democracy. In fact, if read more closely, Democracy for Indonesia is more than a treatise on federalism. There, his idea of Acehnese nationalism began to be dispersed, rejecting the singular concept of "nationalism" in pluralist countries. The character of nationalism, according to him, is aggressive and would be dangerous if it is in the hands of a large ethnicity. For Hasan, what happened in Pulot-Cot Jeumpa was a blow to the wisdom of the Indonesian nationalism. Hasan then jumped to a more radical idea. Perhaps because Darul Islam lost, he shifted his thoughts to Acehnese nationalism. In 196 his pamphlet The Future of Malay World Politics rejected the idea of Republ Indonesia. Hasan said that Indonesia was nothing but a project of "Javanese colonialism and the legitimate legacy of the Dutch colonial war, in other words, denied the transfer of sovereignty from the Dutch to Indonesia 1949. For him, the right to freedom must be restored to the tribes such as Aceh or Sunda had been sovereign before Indonesia was ever since he explored history, wrote numerous pamphlets. In his other work, Atieh Bak Donja's Eyes (A in the Eyes of the World) in Aceh in 1968, he wrote down. after the Dutch War. He began to reconstruct the history of Aceh, and negated all attempts of integration with the republic. Hasan reviewed five New York Times editorials during April of July 1873, the first phase of the Aceh War against the Dutch. He rediscovered the patriotism of Aceh. The famous daily recognizes the capacity of the Aceh Sultanate while fighting against the Dutch. This decisive war, Hasan said, is only possible to be fought because all the heroes of Aceh know how to die "as a man of honor.Here, the idea of" self-sacrifice meets Nietzschean's notion of "free death" "He wants to raise Aceh as a sovereign political entity, as in the past. Hasan then dragged the question of politics into an area of existential struggle in the meaning of life and death. He pointed out that only "free man" and not slave to others could choose "how to live" and "when to die." At first glance he sounds a bit awkward to the minds of the Acehnese people The theme of freedom, or say the flow of thought of existentialism, familiar to those who are great in Western culture, but Hasan understands that the "behavior" to Aceh-an is historically different from the West. He realized, his legs and body were in the East. That is why, Hasan then tried to interpret it in the context of Aceh-an, especially Islam. For him, Islam gave the provision of "the will to power" in guarding and defending the rights. He agreed with Nietzsche's utterance in Notes (1875), which depicted the supreme Muslim figure chanting "the silence of the desert, the roar of a lion, and the stare of a warrior Hasan Tiro understands Islam is energy for Aceh, but he aa different way Haa n mengart L..

in September Nezar Patria -oo5 experiments 1954. Hasan accused Ali of committing genocide "to the people of Aceh, and asked for Hasa Tiro repeated, but Hasan was angry, himself as a refuse, and he was Hasan or Ambassador of Darul Islam in New York. Since then, Hasan has lived as a dissident, and since then we have known that he became a stern critic of Sukarno.In 1958, Hasan wrote an important book in New York titled Democracy for Indonesia, proposing a federal state for Indonesia, the concept of a united state of the Soekarno version. spicy unified state system, which benefits the great ethnic Javanese, and only supports what he calls "primitive democracy. In fact, if read more closely, Democracy for Indonesia is more than a treatise on federalism. There, his idea of Acehnese nationalism began to be dispersed, rejecting the singular concept of "nationalism" in pluralist countries. The character of nationalism, according to him, is aggressive and would be dangerous if it is in the hands of a large ethnicity. For Hasan, what happened in Pulot-Cot Jeumpa was a blow to the wisdom of the Indonesian nationalism. Hasan then jumped to a more radical idea. Perhaps because Darul Islam lost, he shifted his thoughts to Acehnese nationalism. In 196 his pamphlet The Future of Malay World Politics rejected the idea of Republ Indonesia. Hasan said that Indonesia was nothing but a project of "Javanese colonialism and the legitimate legacy of the Dutch colonial war, in other words, denied the transfer of sovereignty from the Dutch to Indonesia 1949. For him, the right to freedom must be restored to the tribes such as Aceh or Sunda had been sovereign before Indonesia was ever since he explored history, wrote numerous pamphlets. In his other work, Atieh Bak Donja's Eyes (A in the Eyes of the World) in Aceh in 1968, he wrote down. after the Dutch War. He began to reconstruct the history of Aceh, and negated all attempts of integration with the republic. Hasan reviewed five New York Times editorials during April of July 1873, the first phase of the Aceh War against the Dutch. He rediscovered the patriotism of Aceh. The famous daily recognizes the capacity of the Aceh Sultanate while fighting against the Dutch. This decisive war, Hasan said, is only possible to be fought because all the heroes of Aceh know how to die "as a man of honor.Here, the idea of" self-sacrifice meets Nietzschean's notion of "free death" "He wants to raise Aceh as a sovereign political entity, as in the past. Hasan then dragged the question of politics into an area of existential struggle in the meaning of life and death. He pointed out that only "free man" and not slave to others could choose "how to live" and "when to die." At first glance he sounds a bit awkward to the minds of the Acehnese people The theme of freedom, or say the flow of thought of existentialism, familiar to those who are great in Western culture, but Hasan understands that the "behavior" to Aceh-an is historically different from the West. He realized, his legs and body were in the East. That is why, Hasan then tried to interpret it in the context of Aceh-an, especially Islam. For him, Islam gave the provision of "the will to power" in guarding and defending the rights. He agreed with Nietzsche's utterance in Notes (1875), which depicted the supreme Muslim figure chanting "the silence of the desert, the roar of a lion, and the stare of a warrior Hasan Tiro understands Islam is energy for Aceh, but he aa different way Haa n mengart L..

Sort: Trending

[-]

brittansiusan (-2)(1) 7 years ago

$0.00

Reveal Comment