Prior to my deployment to Guinea, West Africa as a US Peace Corps volunteer, I was pretty attached to my stuff. Material possessions like music (cassette tapes, this was the mid-90s), clothes and shoes, knickknacks, sentimental items (letters from friends and old boyfriends…yeah, we wrote letters on paper back then), and all the crap that was still at my parents’ house that they hoped I would retrieve someday when I lived in a house and not in my truck.

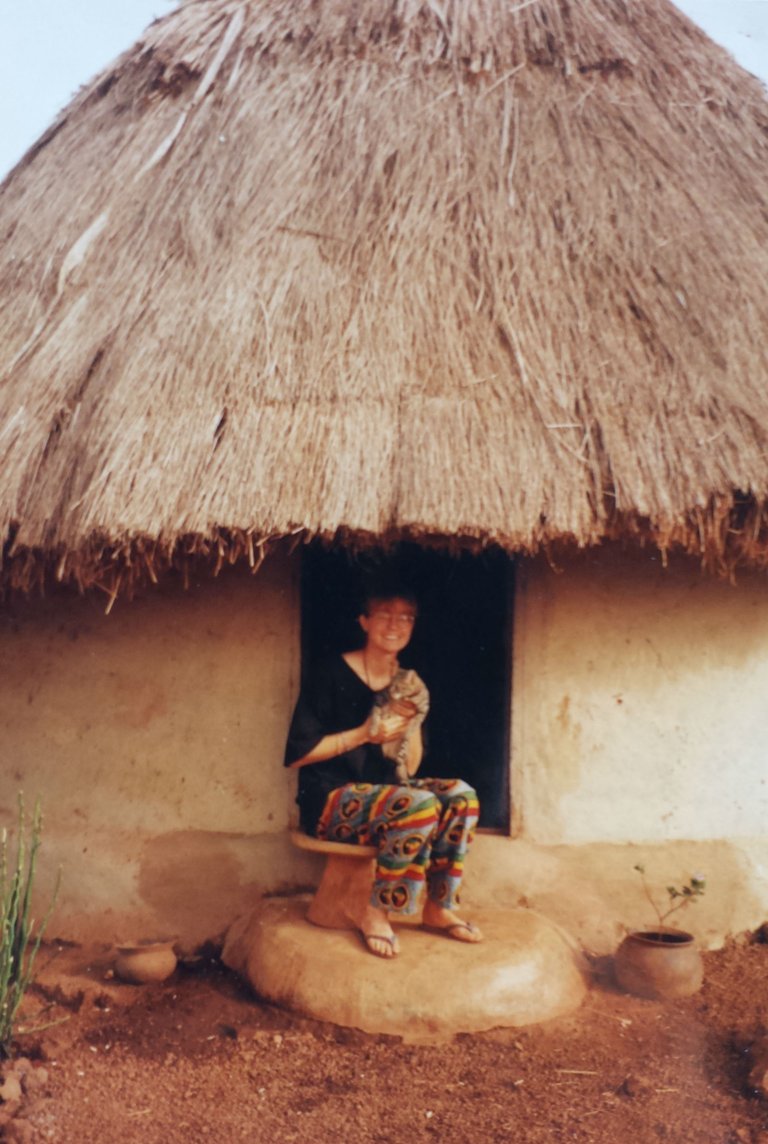

But, there was a weight limit on what I could take…how would I choose? Do they have Q-tips over there? How many books can I squeeze in? How many pretty dresses? And my precious cassette tapes??? (oh to have had a space-saving iPod!). One of my luggage trunks was stolen upon arrival, so I restocked during my three months of training in Senegal, as well as purchased some lovely, locally-made clothes and souvenirs.

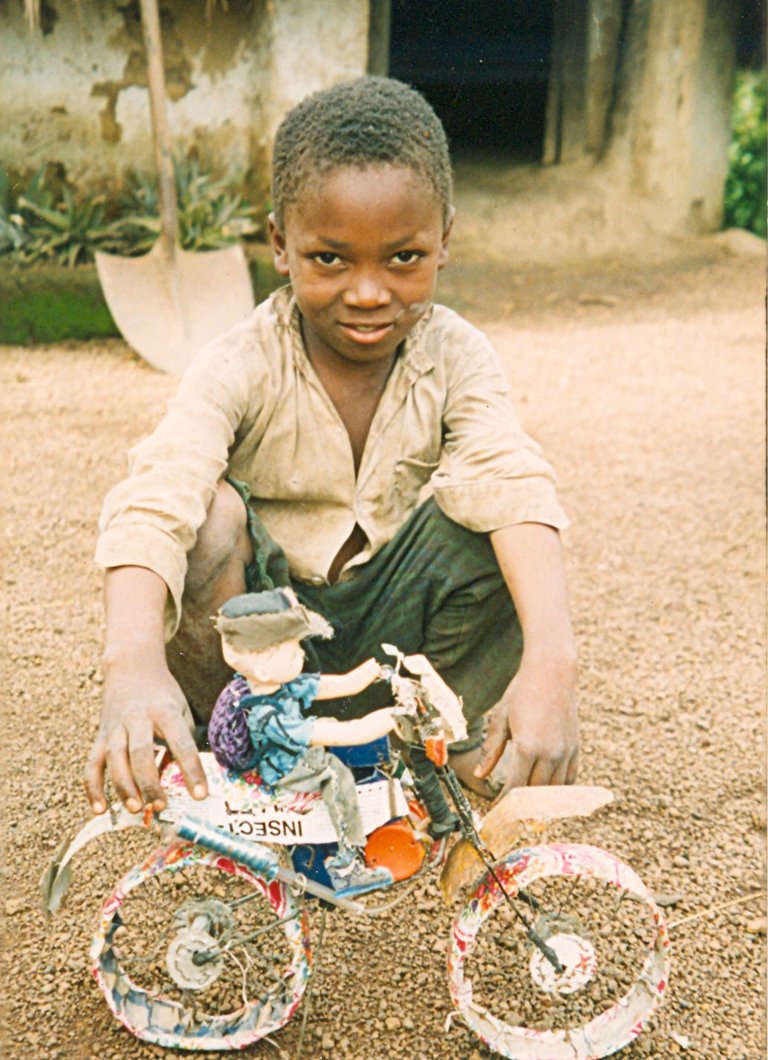

One day, my friend Sef came for a visit. “Hey,” he said, “You’ve got two hats. Give me one!” I found his logic infallible. I never wore both hats simultaneously, so what was the point of having two? So I could flaunt my wealth to the neighbors? I let him choose which one he wanted. Shortly after that lesson, I gave away most of my clothes and wore pretty much the same things daily. After all, my neighbors had only one set of work clothes and one set of nice clothes for going to town.

At my close of service, most of my possessions had gotten wet, moldy, broken, lost, stolen, soiled or eaten by mice and cockroaches, or used for a completely different purpose (e.g., for propping up a short table leg). Anything that was still useable was given to friends. Travel back home was light!

Upon returning to my parents’ house in the U.S., I was overwhelmed by all my stuff. I sold most of it at a yard sale and hauled the rest to the thrift store, keeping only the bare essentials that I packed in my Chevy S10 pickup with space left over to sleep in it as well. For nearly two decades after that, I maintained that if it didn’t fit in the truck, it wasn’t moving with me. And I moved about every six months, so that made it easy not to accumulate!

Even though I have been living in a “real” house for a few years, we didn’t have much decorating our walls or shelves. Thinking that our visitors might consider that odd—and we sort of want to appear “normal”—I recently dredged up a few things that had been in storage for two decades. I’ve sprinkled just a bare minimum around the house to give it that “lived-in” feeling, but I find no sentiment or attachment to these things. And when people give me material gifts, I usually regift them to others that will appreciate them more. If anything is in danger of accumulating, my spirit feels heavy, so I work to keep the ambiance light around me.

How would you feel if you lost your most precious possessions?