The emission of an exceptional high energy light emitted by this star could offer more information about solar magnetic fields.

A recent study by scientists in the United States has found that the Sun is emitting more high-energy gamma rays than expected, according to the Science News portal. But what is really unusual is that the rays with the highest energy arise when the Sun is at its point of least activity, the report indicates.

This is the first research work that has been responsible for analyzing gamma rays during most of the solar cycle, a lapse of about 11 years along which the activity of the Sun increases and decreases.

The team of experts, led by astrophysicist Tim Linden, examined information collected between August 2008 and November 2017 by NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray space telescope. The analyzes incorporated data of low solar activity for a period between 2008 and 2009, another with higher activity in 2014 and a decrease to the minimum activity before the beginning of a new cycle in 2018. The scientists tracked the amount of solar gamma rays that every second they were emitted, as well as their energies and origin.

It was established that over the years analyzed the number of gamma rays emitted became so high (exceeded 50 billion electron volts or GeV) that it exceeded the forecasts. However, surprisingly, the rays that recorded energies above 100 GeV arose only in a period of minimum solar activity.

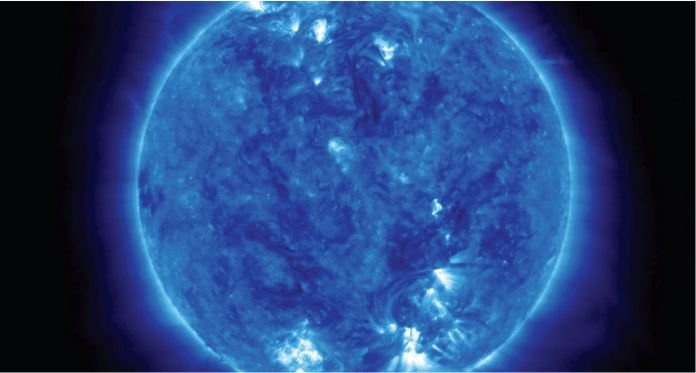

An image taken in September by the STEREO spacecraft shows the Sun in a state of relative calm compared to the last solar maximums.

The terrible conditions on the solar surface.

What is even more strange is that the sun apparently emits gamma rays from different areas of its surface at different moments of the cycle. In the course of the solar minimum, the gamma rays came mostly from an area close to the equator, while along the solar maximum, in which the activity of the Sun was high, the rays gathered around the poles.

This exceptional activity could indicate that the Sun's magnetic fields were "much more powerful, much more changeable and have a much weirder shape than we expected," explained John Beacom, an astrophysicist at Ohio State University in Columbus.

Beacom also noted that high-energy gamma rays could provide new options for studying the magnetic fields of the upper layer of the solar surface, known as the photosphere. According to the expert, "these fields are impossible to see with a telescope, but the cosmic and gamma rays that emit [The fields] are messengers of the terrible conditions that exist in the photosphere."