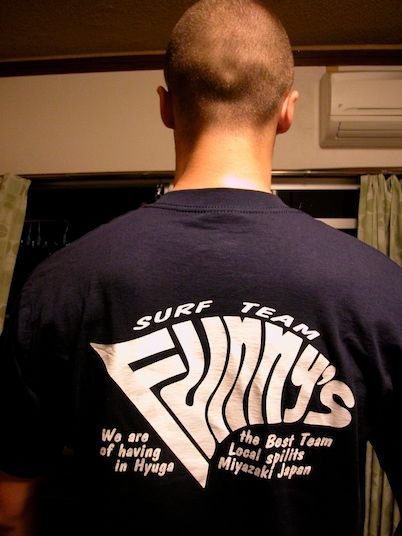

In Japan, it can seem easier to find a shirt for the University of Missouri, or even something that reads, “Possessing the green color is our shared wish”, or “Expose Yourself”, than it is to find a t-shirt for a Japanese city like Hiroshima or Osaka, let alone less heralded locales. So, I was pretty psyched when I discovered the Surf Team Funny’s, “We are the Best Team of having Local Spilits in Hyuga Miyazaki Japan”, t-shirt. I was living in Hyuga. I surfed nearly everyday. And, when I came home to New York, I wanted to wear something that let this be known - To say, hey, I’ve been there to the world, or whatever it is that makes people like me want such things.

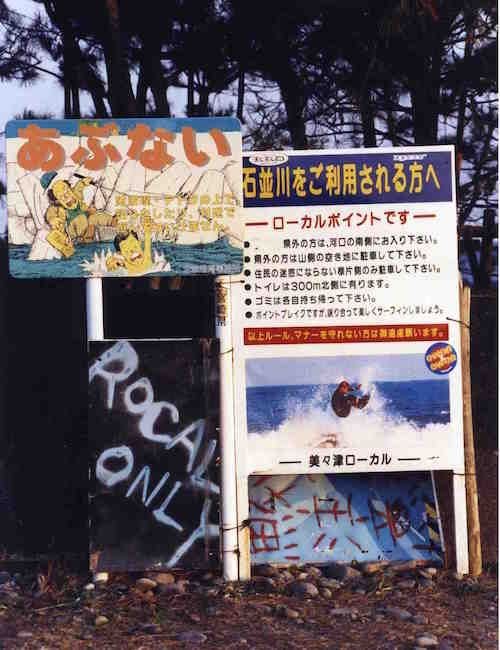

Just when I finally found the shirt, my “spilits” were crushed learning that Surf Team Funny’s was a close knit bunch of locals-only types. A gaijin wearing their shirt would be less than okay. Not only that, but the closed market for Funny’s shirts reminded me that I’d never really be one of the proverbial gang, let alone an actual one. Truly, you can only be a local where you were born, or maybe after living somewhere for considerable time, maybe. When it comes to surfing, this can be especially true. When it comes to Japan, you are subtly reminded of your otherness on a regular basis. But, on the other hand, as a foreigner in Japan I was usually saved from the infamous, and sometimes brutal, hierarchy that constantly serves to remind people of their place in the room, or the water as it may be. Western foreigners are often expected to be ignorant of these local social checks and balances. I had grown accustomed to instant, unearned celebrity status like I received at the bank or the jeans park. Surely, Surf Team Funny’s would make an exception for naïve, only resident foreign surfer in town me.

As my time passed in Japan, I became both less ignorant of social cues, and more aware of my ignorance and naivety. On occasions, I would pretend to not know what was going on when is suited me. Like when the cops picked me up for an unpaid parking ticket I tried to pretend that I couldn’t speak Japanese at all hoping that the cops would grow so tired of trying to communicate with me that they’d just let me go (p.s. they went and got a translator a week later).

A lot of the time though, I really didn’t understand much about my host culture. For example, I never could figure out why tans are still unpopular with most Japanese women, even many that surf? Why do Japanese surfers pay $20 for “jellyfish repellant” that doesn’t work? Why do many Japanese surfers act like they will die a horrible death to walk bare-footed across an asphalt parking lot to the waves? And why does surfing equipment cost so much money in Japan?

As far as US $1,200+ surfboards go, I’ve concluded that Japanese surfers are willing to pay it so surf shops would be foolish to charge any other price? Maybe it as something to do with the communal aspect of Japanese society that I never completely grew accustomed to? Whether that has anything to do with surfboard prices or not, I am convinced that pack mentality is at least partly responsible for the proliferation of surf shops in Japan. As surfing became Japan’s new golf, the surf shop emerged as the de facto country club for many Japanese youths. If you consider that Japanese emphasize the importance of the group over the individual, it is no accident that surf shop affiliation has the importance that it does. Belonging to a surf shop gives a Japanese surfer a name to associate with and a team to belong to. Without it you are ronin. Perhaps this is why so many shops can get away with their exorbitant prices? The customers are paying for the clubhouse.

Indeed, it is through Dear Surf, the shop that I frequented, that I was able to make friends and break through the local ranks and find a privileged place in the lineup. It is through the shop that I became friends with some of the members of Surf Team Funny’s. And it is through the shop that I became close friends with Kouji, Funny’s founder and the artist and creative mastermind behind the t-shirt that I coveted.

One day, I was talking with Kouji and I let on that I really wanted a Funny’s shirt. But even befriending the creator of Funny’s, and its shirt, wasn’t enough. It would not go over well with the rest of the team, he said. I understood and expected this. It’d be like Danny Zuko and Kinikie seeing the Rydell High Japanese exchange student walk by in a T-bird leather jacket. It just wouldn’t be cool.

Hanging out at Dear Surf, going to the parties, and surfing the same beach nearly every day earned me a place in the local hierarchy. Since there are different shops and different circles I didn’t get a green light from everyone. One time I had a brief misunderstanding over a wave with a local Japanese pro from another shop. Very publicly, he reprimanded me in curt, demanding, and heavy-handed Japanese. The American in me contemplated responding with complete disregard for the whole group harmony, hierarchy thing, local pro or not. Back at Dear Surf, it was explained to me that the guy I got in the way of, allegedly, is a pro-surfer, so he needs more waves than me because he needs to feed his family through surfing. Therefore, he has wave priority, and I have to submit - eastern logic I was forced to accept.

Dealing with the intricacies of surfing in Japan, however, was a gift, of sorts. Japanese society is very complex. As a foreigner, I was outside enough, that I was omitted from those complexities and norms. Spending more than two years in the same line-up, in Hyuga, gave me the place where I was truly brought into the fold in a sense. Of course, I would never be a real local in Hyuga, but that’s okay because that’s reality and it’s comforting. It’s nice to be loved, but in Japan, it’s sometimes nice just to be treated like everyone else. I never reached Funny’s status, and I shouldn’t have. Sometimes getting left out is okay.