School has closed for the year, the learners are all enjoying a well-deserved break and I now have some time to myself to catch up on reading all the books I've been meaning to read. I just finished "Inventing the Victorians" by Matthew Sweet. Victorian England fascinates me and it's one of my favourite periods. If I could go back and be a fly on the wall at any time in history, the Victorian period would definitely be high up on the list.

I thought I would share a little of what I read in the book, which, in my opinion, is written very well.

"Inventing the Victorians” challenges the perceptions and images people have of an era largely misunderstood and misread. It is an era in which modern-day people take comfort in having escaped. The book attempts to re-discover the Victorians and view the culture in a different light, acknowledging the links and similarities between "them" and "us". Sweet aims to convince his readers that the Victorian culture was as rich, complex and pleasurable as our own, being one that shaped our lives in many unacknowledged ways. "The Victorians are still with us today, in our bars, our houses, reading our newspapers and inhabiting our bodies." (Sweet, 2001: ix – xxiii)

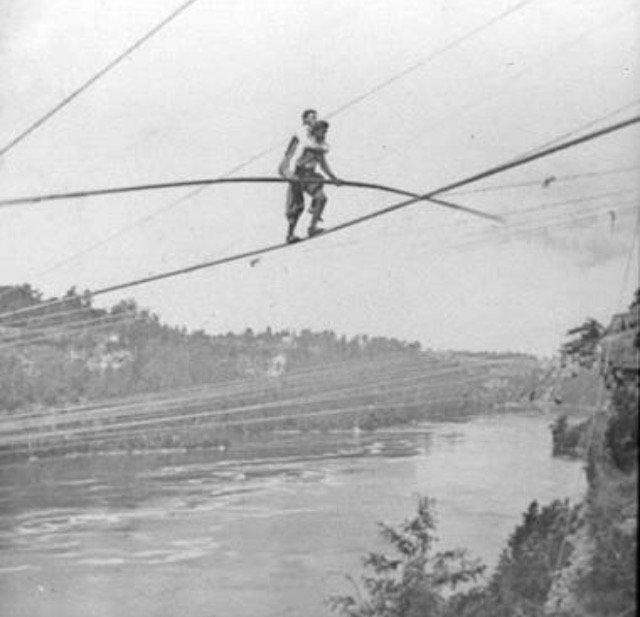

The Victorian era is often mistaken for being boring, strict, "stiff" and prudish. However, it was a period of excitement and entertainment: rail travel, toys, games, magic lanterns, concerts, theatricals, acrobatic displays, panoramas, pantomimes, waxwork shows, dancing dog acts, ventriloquists, magicians and spiritualists were all enjoyed, embraced and even craved. It was the time of the sensation seekers with cravings for sensation at their most extreme with “Blondin”, the 19th century’s greatest icon of spectacular entertainment. His acrobatic performances were raved about throughout the world. (Sweet, 2001: 7)

(Image: http://www.smithsonianmag.com)

Engaging in mesmerizing and extremely risky stunts, audience’s world-over struggled to tear their eyes away from Blondin as he crossed the Niagra falls on a tightrope, their purpose of intrigue often being a secret and subconscious desire to see him fall. This, together with the Victorian’s desire for sensational novelty and the subsequent questioning of the wrong’s and right’s thereof, does not set them far apart from us. (Sweet, 2001: 7)

It's really interesting to learn how the movie camera serves as a mark of dividing the past and the present. The beginning of the 19th century is characterised by sepia photographs, frock – coats and a “straight – backed sort of place” – silent, stiff and stern. However, with the introduction of cinema, the Victorians, and soon the rest of the world, were immersed in film footage of runaway trains and other terror-filled visions as well as performances adapted from existing novels and plays, creating excitement and thrills. (Sweet, 2001: 23) Though most of the authors of these plays and novels were no longer living, some novelists, such as Thomas Hardy, Maria Corelli, Arthur Conan Doyle and Mary Elizabeth Braddon enjoyed making money and selling books through the emergence of moving pictures. The relationship between movie – makers and writers today had thus already been established in the Victorian age. That the Victorians were not accustomed to this plethora of mechanical processes is a misconception. Before the birth of cinema, Victorians found great pleasure in the magic lantern, the mutoscope, the phenakistoscope, and the kineorama, among others. (Sweet, 2001: 24 - 25)

The Victorians are also described as having introduced the first “junk e-mail” in history with a young boy delivering an envelope to a number of Members of Parliament in 1864, which turned out to be junk mail from a dentistry company.

Needless to say, the Members of Parliament were as shocked and annoyed as people in the same circumstances find themselves today. (Sweet, 2001: 38)

The National Provincial Clothing Depot in Bristol was soon to follow, sending out telegrams on a mass – scale, advertising the new clothing range on sale. In 1875 a furniture company sent out 5000 telegrams advertising the new bedstands available for purchase at the depot. (Sweet, 2001: 39) In 1850 the “London Journal” began to publish announcements in the publications, such as “Matrimonial News”. The “London Journal” had in fact turned itself into a textual dating agency, claiming to have been due to popular demand. The Victorians also engaged in correspondence in “The Times”, writing secret, cryptic messages to their lovers, for example. However, the public soon learnt to decipher the messages, resulting in a type of gossip column. (Sweet, 2001: 41)

The very essence and intention of advertising was understood all too well by the Victorians. By the end of the 19th century, many of the world’s biggest brands had been established due to the advertising and marketing efforts of certain groups in this period. Among these brands are Cadbury’s milk chocolate (in 1897), Maxwell House Coffee (in 1892), and Pear’s Soap Company (in 1865). Soon, other promotionary tactics filled the streets in an attempt to address the distrust consumers felt towards claims made about products and services. Releasing helium balloons with a company’s name printed on them and decking London omnibuses with flags are just a few examples. Thus, promotionary tactics are not a product of the “more modern” 20th century. (Sweet, 2001: 52)

For the first time in history people also realised that photography as a medium could increase their fame and prestige. (Sweet, 2001: 59) The “professional beauty” was a new kind of public figure. One example is Lillie Langtry. It was not her acting abilities that were of interest but rather her long – winded affair with the Prince of Wales that made her seem fascinating to many people. She, along with other celebrities of her day, used the newspapers to facilitate their fame, making these stars to seem to be far removed from reality. The sex scandal was not a Victorian invention; however the sensational stories of sexual exposure were intensified in this period. (Sweet, 2001: 60) The “Pall Mall Gazette”, and others like it, immersed readers in sensationalistic stories of English girls being kidnapped and forced into slavery in Belgium, of Elizabeth Armstrong as a hopeless drunkard and of Governor Cleveland’s sexual relations with “commoner” Maria Halpin, among other stories. (Sweet, 2001: 61, 66)

(Image: www.oldpicz.com)

Sweet (2001, 71 – 72) then delves into Victorian England’s most notorious prisoner, Dr William Palmer. He was sentenced to execution in 1856 after having been found guilty of poisoning sixteen people. His story is echoed in that of Dr Shipman, who was found guilty of killing at least fifteen of his patients with prescription drugs in 2000. The murders are described as being done with style as opposed to today’s murders being carried out by less distinguished “gangster wannabe’s”. The Victorian killer was a gentleman or lady amateur. (Sweet, 2001: 75) Along with pornographic and religious works, the accounts of crimes have always been a focal point of the publishing industry, with readers desperately seeking the gory details in newspapers or periodicals. Today the webpage for serial killers is highly sought after. A great number of people attended the executions in the Victorian period and their interest in the horrifying stories is evident with the establishment of the Chamber of Horrors at Madame Tussaud’s – which is still an attraction today. (Sweet, 2001: 77 – 79)

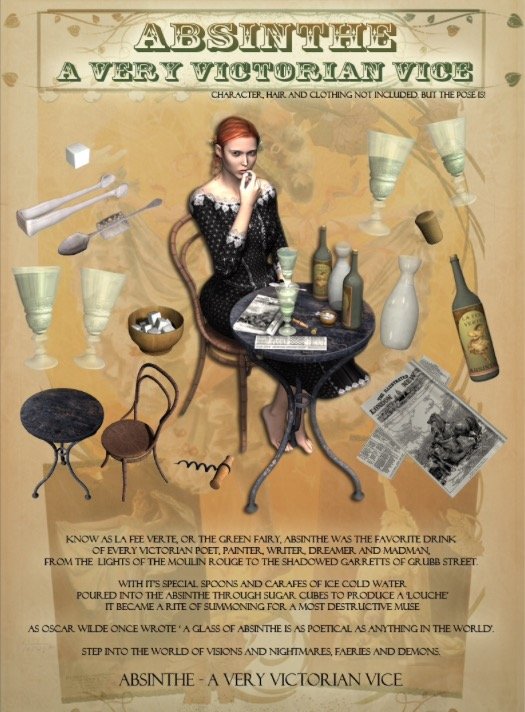

The author later spends some time on the Victorians being avid “pill poppers”. “Opium was the opium of the people” – teething babies were given a mixture of black treacle and opium, bored suburbanites inhaled opium from their handkerchiefs, the chronically ill used it as a painkiller and the hungry used it as an appetite – suppressant. (Sweet, 2001: 97) With this in mind, it is difficult to think of the Victorians as being “stodgy”.

However, in the next few chapters Sweet elaborates on the view most people share of the Victorians in this regard as he tries to concentrate on the sensational and permissive aspects of Victorian culture, obscured by Strachey and Freud. (Sweet, 2001: 105) The image of Victorian social events, and food in particular, is a negative one. However, Sweet describes Victorian food as not being nearly as boring. French cuisine was introduced to the English, Vegetarianism also became popular and Victorian recipes reveal the variety of 19th century food. A recipe on how to make spinach puree, omelette soufflé and lobster sauce is just one example. (Sweet, 2001: 106 – 107) The social codes, too, seemed particularly stodgy. However, Sweet unravels the practical relevance of these. The rejection of cheese by ladies at dinner parties, for example, can be ascribed to the harmful bacteria found in this product. (Sweet, 2001: 108) Thus, some of the Victorians practical intentions have been obscured and mistaken as being “stodgy”. (Sweet, 2001: 105)

(Image: www.renderosity.com)

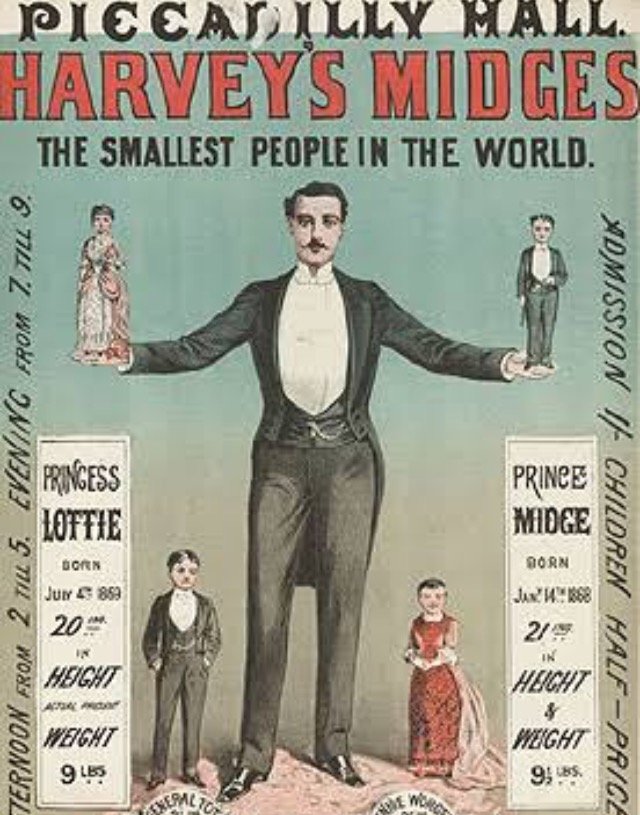

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries the exhibition of bizarre curiosities was a thriving industry. Appearances at, for example, the Hyde Park Fair, exhibited numerous spotted boys, a two-headed lady, fortune-telling ponies, dwarfs, dog-faced boys, baboon women and giants who, Sweet (2001, 140) describes, should be celebrated today as they were in those times and should not be forgotten in the archives of hospitals, forensic labs and museums.

(Image: www.bl.uk)

These exhibitions uncover the brutality of the Victorians, their willingness to exploit the unfortunate. The dwarfs, giants and pig-women have all sunken from view. Interestingly, “the bear woman and the baboon lady” (a woman completely covered in thick brown hair) was of great interest to gawking Victorians. After her death, her mummified body was also “successfully” exhibited throughout Europe in the 20th century. (Sweet, 2001: 142 – 143) Thus, Sweet (2001, 143) argues, to expose the Victorians as ghoulish and horrid would be an exposure of the same qualities of people of the 20th century. What is often left out of Victorian history is that these so called “freaks’ were not seen as being at a disadvantage or as unfortunate beings. They were celebrated and were paid very well. (Sweet, 2001: 146 - 148) Also, the term “freak” was not often used. These “performers” were referred to as prodigies. (Sweet, 2001: 146)

(Image: http://www.virtualvictorian.blogspot.co.za)

Sweet (2001, 156 - 157) explores the history of childhood and childhood innocence. Josh Calvin believed that children were creatures of innate evil and only education would teach them of the habits of virtue. It was only when John Locke expressed his views of children needing to be treated like rational, innocent creatures that the concept of childhood was re – examined. The Romantic Movement renegotiated the terms of childhood and the Victorians later sanctified and protected their children through legislation. (Sweet, 2001: 160) Sweet describes the similarities between the murders of Fanny Adams in 1867 and Sarah Payne in 2000, both killed by paedophiles. Both incidents brought about public sentimental religiosity in response to innocence destroyed. The author offers an interesting take on the subject and explores how romanticized images of children in the mid and late – 19th century may now appear to be slightly overwhelming and creepy. It is described as one of the key injustices with which the Victorians can be charged – the generating of a sentimental eroticism around childhood. (Sweet, 2001: 161 – 164)

The issues of gender roles and masculinity of the Victorians comes into question. That women were creatures for sweet ordering, arrangement and decision in the home is exposed as being an untruthful stereotype. Conversely, that Victorian men were the discoverers, the creators and open for peril and trial is also questioned and it is revealed that, not only were women often actors, pawnbrokers, pen grinders, rope - makers and blacksmiths, but the men were as domestically inclined as women and spent a great deal of time looking after the children at home. (Sweet, 2001: 178 - 182)

Also worth mentioning is the insecurity Victorian men felt with regards to their masculinity. Thus, the crisis of masculinity, which many 21st century men endure today, had already begun in the 19th century. (Sweet, 2001: 183)

Linked to the topic of masculinity is that of sexuality. Pornography is described as having been one of the major industries in Victorian Britain. In many of these kinds of publications, the erotic encounters between men were staged, with surprising ease and willingness. The opposition between homosexuality and heterosexuality, which today is regarded as being very important, did not exist in the 19th century. (Sweet, 2001: 196)

The Victorians are described as being "erotic” and open about sex. A large number of essays were published during the Victorian period, discussing the topic of sex in great detail and depth. (Sweet, 2001: 210 - 211) Thus, with their pornographic texts and notions about homosexuality and related issues, Sweet challenges the notion of a stuck – up, rigid, “prudish” and stodgy Victorian society for a more passionate, intimate and eccentric one.

(Sweet, 2001: 212)

Sweet (2001, 229 -230) concludes by asking (and answering) the question of what can be done in order to liberate the Victorians from the perceptions and images 21st century people have of them. Once the Victorians are no longer needed to fulfil the role of blame in order to make ourselves look and feel better, it will be our grandchildren who will cast us into this role. The wars, the free market, the laws dealing with immigration, sexual orientation and gender are just some of the aspects of the 20th and 21st century that may be criticised.

What is the general feedback on "Inventing the Victorians"?

“Inventing the Victorians” is divided into fourteen well-constructed, well-written and well-balanced chapters. The author, Matthew Sweet, sets out to “re - imagine” the Victorians and rid the 21st century of the myths of the 19th century. It sets out to destroy the stereotypes still held about Victorians. For a historian of the period, this work is probably not of startling significance, however, it does illuminate the fact that whatever our attitude toward the 19th century is, it actually tells us more about ourselves than about the 19th century. (Inventing the Victorians, n.d.)

This work is deemed invaluable to anyone wishing to escape stereotypes of the Victorian past. It is described as being provocative in a way which makes one think. The style is informal, the grammar is good and the concepts are easy to follow. Sweet ensures the inclusion of real-life Victorian people in order to create greater understanding, and a stronger sense of the time. The books' strength lies in how Sweet constantly compares the 20th and 21st century to the Victorian period. (Inventing the Victorians, n.d.)

I hope you've enjoyed rediscovering the Victorians as much as I have, thanks to Matthew Sweet's "Inventing the Victorians". I had been wanting to read the book for quite some time and can say I was not in the least disappointed. I find the Victorians fascinating and somewhat peculiar!

Cheers,

@lynb

Sweet, M. Inventing the Victorians. New York. 2001.

Images:

Wikipedia

www.renderosity.com

www.historyinanhour.com

www.victorianera.org

www.bl.uk

www.virtualvictorian.blogspot.co.za

www.oldpicz.com

www.smithsonianmag.com

It quite seems like you enjoyed this book. Isn’t it nice to immerse yourself into another world for a few days? I am hooked on Victorian period movies. I rarely have a chance to read. Good to hear you are relaxing.❤️🐓🐓

I agree wrt Victorian period movies.

Thanks for taking the time to read my blog. I appreciate it very much. Xx