Frankfurt, Germany Caracas Venezuela. A sneeze at the wrong time, some fever, symptoms that in principle fit with a common flu. Just a few weeks have passed and it seems that that simple cold is something worse, not only for its spread (400 infected) but also for its dangerousness (50 dead). The political and health authorities come together to react to the expansion of Clade X around the world through the US soldiers. One fateful day, a student on a New England university campus coughs. It's too late. In just over a year and a half, about 18 months, 150 million people, 10% of the world's population, have died.

Readers may remember 'Contagious', Steven Soderbergh's film, or the 'Pandemic' board game. Both cases try to reflect what would happen in case of extreme global pandemic. It may seem catastrophic, but a recent simulation by the Center for Health Security John Hopkins has shown that the worst scenarios presented in scientific fiction may fall short. In other words, we are not prepared for the appearance of a new pathogen "moderately contagious and moderately lethal". We are not even for a dangerous mutation of the flu.

The simulation took place on May 15, in a conference room that looked like the set of 'Red Telephone: Are we flying to Moscow?' Over the course of a day, politicians (such as Democratic Senator Tom Daschle), military and experts (such as CDC Director Julie Gerberding) formed a Presidential Security Council in which they should react as they would have done in the event of a threat. real. The narrative was presented in four different phases that posed new challenges. It should not have gone very well in this fictional videogame, because they could not prevent millions of people across the planet from dying between nausea and extreme fevers, before falling into the coma

The summary of the simulation, which has been published as a video, is eloquent. It is the faces of gravity of the participants before the videos that show how the death meter rises without stopping. Also how they get uncomfortable in the seats before some of the moral dilemmas that arise, for example, what would they do if Venezuela asked for financial support from the US because of its inability to shelter all the sick people in hospitals? It is something existential, USA it has just been erased from the map in the last six hours! "complains the former simulator Jim Talent, who plays the Secretary of Defense, visibly nervous. The worst of all? That, as the presenter reveals at the beginning of the simulation, the scenario designed for this test is the most likely statistically speaking. That is, they have not exaggerated a hair.

Valuable lessons

Even terrifying, the experiment aims to awaken a new consciousness among the political and health authorities of developed countries: until now, we have been lucky, recall John Hopkins researchers, but it may not be enough next time. Other experts agree. As recently recalled by John M. Barry, one of the great global experts in pandemics and author of 'The Great Influenza' - which focuses on the Spanish 1918 -, our global preparation for a hypothetical similar threat receives an approved scraping. The big problem, remember, is that we lack a universal vaccine against influenza, so the next mutation can be lethal.

In the scenario proposed by John Hopkins, the virus had been created by a group of terrorists called A Brighter Dawn ('A brighter dawn') with the aim of reducing the global population to return to levels of the eighteenth century. However, those responsible have recalled that if it were a pathogen that appeared naturally, the reaction would not be very different. "We have learned that even public officials with knowledge, experience and determination who have faced many crises would have problems dealing with something like that," Dr. Eric Toner, simulation designer, told Business Insider. "It's not because they're not good enough, but because we do not have the necessary mechanisms to provide that kind of response."

The executive report of the project includes the six policy recommendations that the Center proposes to the US authorities to prevent the experiment from actually deriving: developing the capacity to produce new vaccines and drugs for new pathogens in a matter of months (not years); to be pioneers in a global, strong and sustainable social security system; build a national social security system that can respond to a pandemic; develop a national plan to take advantage of all the resources of the US health system in a catastrophic pandemic; implement an international strategy to keep research under control that increases the risk of a pandemic; and make sure that the national security community is prepared to prevent, detect and respond to this kind of emergencies.

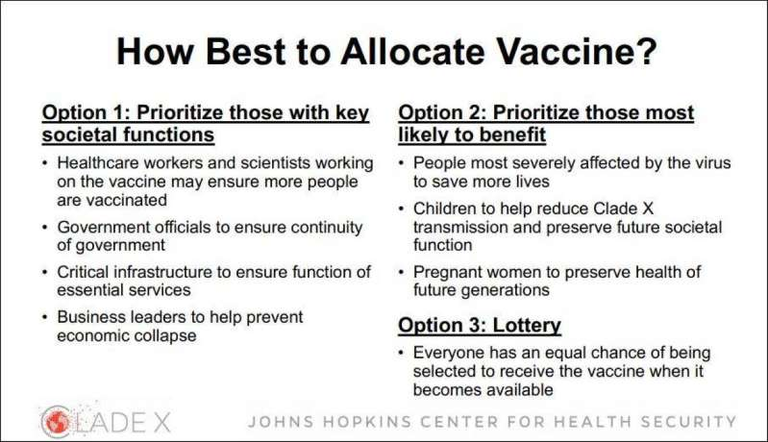

One of the examples of decisions that the committee should make: how would you distribute the vaccines?

What the system shows is that the ramifications of a hypothetical pandemic are not very predictable. Barry, for example, puts the emphasis on the supply chain. What would happen if, for example, a third of the air traffic controllers in a country fell ill? Or if the drivers of the big railroads that transport the coal that supplies energy to the entire US from Wyoming did it? A pandemic means creating a common political and health front that is increasingly utopian, at a time when economic, political and national interests are increasingly fragmentary. Of course, there is neither a global system for these cases nor the capacity to give immediate assistance to the infected patients or the willingness to leave the partial interests aside.

The threat of the Nipah

It is not the first simulation carried out by John Hopkins, which has already launched Dark Winter ('Dark Winter' in 2011) and Atlantic Storm ('Atlantic Storm' in 2005), with very similar results. If the first scenario made a hypothesis at the local level, the second scenario included the NATO countries, with special emphasis on Europe and with the famous US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright as one of its main figures. Revealingly, the first of these scenarios inspired the video game 'Tom Clancey's The Division'.

It is possible that these experiments return to the heads of epidemiologists every time a new threat emerges. The latest of these has been the Nipah virus, which last May killed at least 10 people after a new outbreak in southern India. The virus, discovered in 1998 in Malaysia, lacks a vaccine, since the number of people affected by it has always been reduced. In other words, there is not enough interest to develop a specific treatment, something common to many of these outbreaks.

That does not prevent it from being a potentially very dangerous virus. As pointed out by the epidemiologist at Harvard University Stephen Luby, one of the great specialists in this strain, "emerging infections can be great threats." This is what happened with Ebola, which "showed that hospitals in poor countries are important places for the transmission of potentially pandemic organisms". The problem, he adds, is that since we can not know what the next pandemic will be, it is impossible to vaccinate the global population. What can you do then? In his opinion, act long before and find mechanisms so that the disease is not transmitted in hospitals in poor countries. Only by stopping it there can be prevented from jumping to the developed countries, the moment when, sadly, it is when most of the population begins to worry. I mean, late.

Great post. post more and will support for it. thank you. do the same for me too. :-)

buen post gracias.

felicitaciones por tu publicacion martinalex.

felicitaciones por tu publicacion martinalex.