The first Rare Digital Art Festival, aka Rare AF, aka Rare as Fuck, was held on a cold January Saturday in the offices of Rise New York. The organizers, Kevin Trinh and Tommy Nicholas of the Rare Art Registry Exchange, had announced the event only a few weeks earlier, but by midmorning, the airy coworking space was swarming with crypto boosters and speculators, gamers, meme aficionados, artists, and collectors. This unlikely crowd (mostly young men, though I heard one audience member marvel at “all the women” present) had gathered for panel discussions, demos, an initial-coin-offering announcement, free sandwiches, and a live digital-art auction. Like many tech events, the aim of the conference was ambitious bordering on grandiose: the attendees of Rare AF believed they were witnessing history. They were certain that blockchain technology would reshape the future of digital art for years to come.

All the panels shared an underlying premise: The rise of digital media has made every kind of art widely accessible, but it has also created many problems. Because people can copy and share files freely and infinitely, artists don’t receive compensation for their work. Worse, an increasingly powerful cadre of middlemen services (Amazon, Spotify, etc.) have been fracturing the media landscape while reaping almost all of the profits.

Enter the blockchain, a decentralized and immutable ledger of digital transactions with the power to reintroduce scarcity and property rights to the digital-media economy. Many conference participants held strong beliefs about the superiority of a particular blockchain (Bitcoin vs. Ethereum), but for artists and collectors, the processes and results of these competing cryptocurrencies are fairly similar. An artist creates a limited-edition crypto collectible—the digital equivalent of a signed print—and exchanges it with a buyer for some cryptocurrency. The new buyer truly owns this digital object; they can keep it in their crypto wallet, show it off in a virtual gallery, or project it from a digital picture frame hung on their wall—a service offered by panelist Vladimir Vukicevic’s company Meural. Just as you can share reproductions of the Mona Lisa, someone could still copy and paste the image, but the provenance and price history of the original are accessible to all. The original of these works is identifiable and cannot be replicated, which is why they are called “provably rare.” Kieran Farr, a panelist representing a virtual-reality platform called Decentraland, summed things up to a round of applause: “Finally, authenticity has value.”

The most basic application of this technology comes in the form of digital collectibles and in-game purchases. These are items that artists or developers have either created whole cloth or licensed from preexisting brands—the digital equivalent of Star Wars figurines, baseball cards, or Beanie Babies. Crypto artists and collectors assess the value of their products in four ways: intrinsic (Do you personally like it?), extrinsic (Does it make you look cool?), utility (Can you do stuff with it?), and store of value (Will it maintain its worth?). The most successful crypto collectibles will not merely sit on your desktop—they will be unbearably cute, the envy of your friends, able to interact with other digital objects in a digital world, and maintain or go up in value.

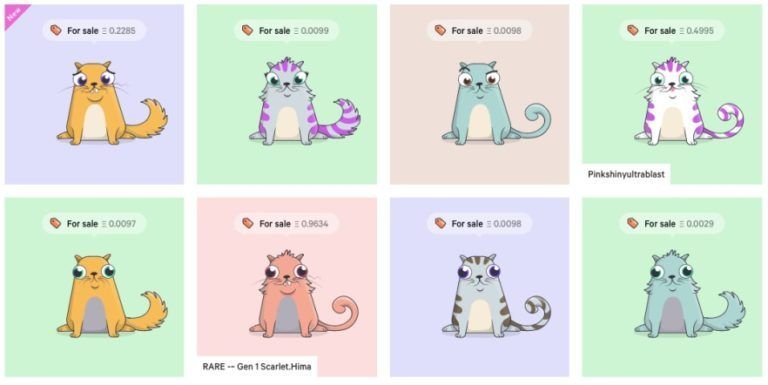

CRYPTOKITTIES

So far, collectors have mostly ignored these questions, focusing on the novelty of the underlying technology. In the past year, whole ecosystems of collectibles have sprung up. The most famous of these is CryptoKitties, a game where collectors breed and trade digital cats. The game is so inexplicably popular that, recently, rare CryptoKitties have sold for as much as 253 Ether, which at the time of sale on December 6 was equivalent to just over $110,000 (and, as I write this, is now worth about $251,000). During the CryptoKitties Q&A, an audience member asked Dan Viau, the founder of an app devoted to selling hats and costumes for CryptoKitties called Kitty Hats, whether the company was concerned that CryptoKitties were being used to launder money.

“If you were a money launderer,” he replied, “I think it would be malpractice not to use CryptoKitties.”

Though the crypto collectible market is frothier than ever, traditional fine-art collectors have been slower than the Reddit crowd to adopt blockchain. During a talk called “How the Blockchain Changes the Game for Artists,” panelists agreed that the technology offered great value to artists but were concerned about the structural issues posed by introducing it to the museum world. Michael Xufu Huang—a New Museum trustee and cofounder of the Beijing museum M Woods—expressed reservations. “I’m a little skeptical,” he said.

The history of digital-art collection has been one of beneficence; institutional collectors typically choose to pay artists because curators deem their work important and want to preserve and archive it, but most digital art has no resale value because it cannot be rigorously authenticated. The advent of blockchain is poised to change that.

But major art collectors have been hesitant: they value discretion and exclusivity. Institutions, who would have the power to shift the art world toward this development, have been risk averse. Though MoMA, the Whitney, and the New Museum (and their digital-art affiliate, Rhizome) have amassed or commissioned significant holdings of digital art, none of them currently own any work disseminated or purchased through a blockchain. (The Whitney, however, is in the process of commissioning a blockchain work by Jennifer and Kevin McCoy to be launched in spring 2018.)

Despite these headwinds, individual artists are beginning to show interest in the technology. Sotheby’s graduate student Jess Houlgrave presented a roundup of artists who had used blockchain in their recent work: Simon Denny created a crypto-themed version of Risk called Blockchain Future States for Petzel Gallery; Ed Fornieles developed a series of Tamagotchi-like creatures called Finiliars, whose health and happiness are algorithmically tied to the fluctuations of various market instruments and cryptocurrencies; and Sarah Meyohas minted her own parodic cryptocurrency back in 2015 called Bitchcoin. In their own ways, each of these artists is exploring the technological, economic, and cultural properties of the blockchain. The most compelling work to come out of the panel, though, wasn’t somebody Houlgrave mentioned but rather a fellow panelist deeply embedded in meme culture: DJ Pepe. On stage, he appeared as a six-foot cardboard cutout of a frog man hunched over an invisible set of turntables. Attendees and fellow panelists addressed their questions to the cardboard DJ Pepe, while his creator and “manager,” DJ Scrilla, answered over the PA system from the back of the room.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/01/23/much-pepe-scenes-first-rare-digital-art-auction/

A great post to showcase the need of progress and the importance of Blockchain in it.

Yea thanks alot.

Lets hope so! TronDogs to the moon. #CryptoRising #TronDogs #Tron #TRX

![tron-[Recovered].png](https://images.hive.blog/768x0/https://steemitimages.com/DQmdKnLAME5rZVP4bvFKqvxPk9KAqbWn8yNbM94wqsBsWfs/tron-%5BRecovered%5D.png)

Yea great work!!

Nice post!

Thank u!!

Nice work

Tnks mane!!