How do you do?

Welcome to the fifth of eight posts chronicling my Summer 2024 exploration of downtown Chicago museums and other attractions:

B1: Chicago Overview, CityPASS, & Millennium Park

B2: Field Museum of Natural History

B3: Shedd Aquarium

B4: Museum of Science and Industry

B5: Art Institute of Chicago (Part 1) (this post)

B6: Art Institute of Chicago (Part 2)

B7: Willis/Sears Tower Skydeck, the Rookery, Chicago Fed Money Museum, Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago Cultural Center, & Design Museum of Chicago

B8: Medieval Torture Museum (NSFW)

This post will mainly be sharing the various pieces of artwork that I found most impressive or interesting at the Art Institute, along with some cute animal art. I had to break this post up into two parts due to size limits when posting. This post covers European art, Medieval & Renaissance, Arms & Armor, and Arts of the Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Worlds.

All of the pictures in this post were taken by me except for the five map images of the museum.

ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO

Michigan Avenue Entrance

111 South Michigan Avenue

Chicago, IL 60603

Modern Wing Entrance

159 East Monroe Street

Chicago, IL 60603

Website: https://www.artic.edu/

Hours:

The Art Institute is CLOSED on both Tuesdays and Wednesdays!

The first hour of every day, 10 A.M. – 11 A.M., is reserved for member-only viewing.

The Art Institute is open to the public every day (Thursday through Monday) from 11 A.M. – 5 P.M. On Thursday it is open later for another 3 hours, closing at 8 P.M.

Cost (as of 2024):

General Admission:

Adult: $32

Seniors (65+): $26

Students: $26

Teens (14 – 17): $26

Children: Free

Members: Free

Illinois residents get a $5 off discount.

Chicago residents who are adults, seniors, or students get a $12 off discount instead. Chicago Teens (14 – 17) get free admission.

Fast Pass for expedited entry costs an additional $8.

Free admission is offered to Illinois residents on select days (Thursday evenings 5 P.M. – 8 P.M. from June through September, certain days 11 A.M. – 5 P.M. in October or November).

Free admission is available to current Illinois educators, including pre-K – 12th teachers, teaching artists working in schools, homeschool parents, and active-duty service members. Chicago Public Library cardholders 18 and older can also register to obtain free admission.

Students of colleges and universities in the University Partner Program are entitled to free general and special exhibition admission as are employees of certain companies in the Corporate Partner Program and members of the Cultivist art club.

Chicago C3 provides general admission while the full Chicago CityPASS provides fast pass admission.

Estimated Time: 4 - 5 hours, but you could easily spend 2 - 3 full days exploring all of the content in the museum.

On this visit I spent 4 hours and I could have easily spent more. Being familiar with the Art Institute already, I rushed through many of the exhibits that I had seen before, spending more time on newer exhibits and on taking pictures for this blog. Someone new to the Art Institute or intent on reading every informational display would only scratch the surface in 4 hours.

SUMMARY

Here are some maps of the Art Institute. Most of the exhibits are on the first two floors. The modern wing is a separate building but connected. A few areas have a lower level and the modern wing has a third floor.

The Art Institute of Chicago is a world-class art museum worthy of 5 stars. It is my favorite art museum due to the breadth and depth of its collections.

Here is how I would compare the Art Institute to other art museums:

5 stars:

- Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago, IL)

- Castello Sforzesco (Milan, Italy)

- Philadelphia Museum of Art (Philadelphia, PA)

- Sydney and Walda Besthoff Sculpture Garden (New Orleans, LA, Free)

4 stars:

- The Ringling (Sarasota, FL)

- Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nice (Nice, France)

- Musée Masséna (Nice, France)

- Musei di Strada Nuova (Genoa, Italy)

- Villa del Principe (Genoa, Italy)

- Pinacoteca Ambrosiana (Milan, Italy)

- Rodin Museum (Philadelphia, PA)

- Indianapolis Museum of Art (Indianapolis, IN)

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (San Francisco, CA)

- Legion of Honor (San Francisco, CA)

3 stars:

- Musée Matisse (Nice, France)

- Palais Lascaris (Nice, France)

- Musée Picasso (Antibes, France)

- Museo Diocesano (Genoa, Italy)

- Triton Museum of Art (Santa Clara, CA, Free)

- de Young Museum (San Francisco, CA)

- High Museum of Art (Atlanta, GA)

- New Orleans Museum of Art (New Orleans, LA)

2 stars:

- Museum of Contemporary Photography (Chicago, IL, Free)

- Design Museum of Chicago (Chicago, IL, Free)

- Musée de la Photographie Charles Nègre (Nice, France)

- L'artistique (Nice, France, Free)

- Musée Peynet et du Dessin Humoristique (Antibes, France)

- Museo di Sant'Agostino (Genoa, Italy)

- Museo del Novecento (Milan, Italy)

- San Jose Museum of Art (San Jose, CA)

And if you want to compare to non-art museums:

5 stars:

- Field Museum (Chicago, IL)

- Castello Sforzesco (Milan, Italy)

4 stars:

- The Ringling (Sarasota, FL)

- Museum of Science and Industry (Chicago, IL)

- Museum d'Histoire Naturelle (Nice, France) (2 stars without the Lego special exhibit)

- Musée Masséna (Nice, France)

- Galata Museo del Mare (Genoa, Italy)

- Museo del Duomo (Milan, Italy)

- CDC Museum (Atlanta, GA, Free)

- Mardi Gras World (New Orleans, LA)

- World War 2 Museum (New Orleans, LA)

3 stars:

- Chicago Fed Money Museum (Chicago, IL, Free)

- Medieval Torture Museum (Chicago, IL)

- Musée d'Archéologie de Nice-Cimiez (Nice, France)

- Civico Museo Archeologico (Milan, Italy)

- Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci (Milan, Italy)

- Museo di Storia Naturale (Milan, Italy)

- California Academy of Sciences (San Francisco, CA)

- Michael C Carlos Museum (Atlanta, GA)

- Center for Puppetry Arts (Atlanta, GA)

- World of Coca-Cola (Atlanta, GA)

- Fernbank Museum of Natural History (Atlanta, GA)

2 stars:

- Musée d'Archéologie d'Antibes (Antibes, France)

- Museo Civico di Storia Naturale Giacomo Doria (Genoa, Italy)

- Museo del Tesoro di San Lorenzo (Genoa, Italy)

- Museo Biblioteca dell'Attore (Genoa, Italy, Free)

- Holcomb Observatory and Planetarium (Indianapolis, IN)

- San Jose History Park (San Jose, CA, Free)

- Museum of Illusions (Atlanta, GA)

- Atlanta History Center (Atlanta, GA)

1 star:

- National Center for Civil and Human Rights (Atlanta, GA)

My favorite section is probably the European art galleries. There is a small but respectable section on Medieval and Greek/Roman/Byzantine art. There are several impressive windows ranging from Chagall's American Windows to various Tiffany glass windows. Although easily missed because it is on the lower level, the Thorne Miniature Rooms are always one of the highlights of my visits - you should definitely check them out! Then I cover American Art, Modern Art, Asian Art, Art of the Americas, and the Photography gallery in the lower level. (The African exhibits were closed during my recent visit).

The Art Institute is home to many famous and well-known pieces of art so a lot of the fun is to see the real authentic piece up close (examples include Two Sisters (On the Terrace), A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, Paris Street; Rainy Day, van Gogh's self Portrait and The Bedroom, American Gothic, The Child's Bath, Nighthawks, Golden Bird, and On the Threshold of Liberty). Seeing the finer details or immense size, often makes you better appreciate the effort and skill required to create such masterpieces. There are also plenty of lesser known pieces by famous artists. But even among the remaining pieces by artists you may not be familiar with, there are still lots of beautiful or thought-provoking artworks to admire and scrutinize. And of course, if you take the time to read the informational displays, you can also learn more about the historical periods and the artists.

Since a lot of art is visual, a lot of this post is sharing pictures of my favorite pieces. One way to go through this post is just to scroll through the images. I've also included in italics details and descriptions that the Art Institute provides, so if you want to learn more about a particular piece you can read about it. My personal comments will be minimal and in the handful of cases where I make them they will be underlined.

I have noticed that sometimes my pictures don't turn out completely even. Sometimes that is intentional - to avoid glare or reflections (of myself or others), I have to take the picture at an angle. Sometimes the physical space forces you to take a picture at an angle - this is especially the case if you aren't perfectly centered and/or the painting is at a different height. Otherwise, a painting might not be perfectly level, my phone might be imperfect, I might physically view things differently, or it is hard to keep my hand steady when I'm rushing to take a picture!

OUTSIDE

Lion (One of a Pair, South Pedestal), 1893

Bronze with green patina

Edward Kemeys (American, 1843 – 1907)

American Bronze Founding Company

Chicago

Iconic guardians of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Lions have stood at the Michigan Avenue entrance since the building’s inaugural year. The site became the museum’s permanent home at the conclusion of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, where the new structure had hosted lectures and other events for fairgoers. Modeled by Edward Kemeys, an essentially self-taught artist and the nation’s first great animalier (sculptor of animals), the lion pair was unveiled on May 10, 1894. Kemeys focused his talents on sculptural portrayals of North American wildlife, capturing such native creatures in anatomical, naturalistic detail. For the Art Institute, he modeled larger-than-life African lions, the one positioned north of the steps “on the prowl” (1893.1b) and the lion to the south “in an attitude of defiance,” in Kemeys’s words. These behavioral distinctions are visible in the variation of head, tail, and stance. Each weighing in at more than two tons, the Lions were cast in Chicago by the American Bronze Founding Company.

Gift of Mrs. Henry Field

1893.1a

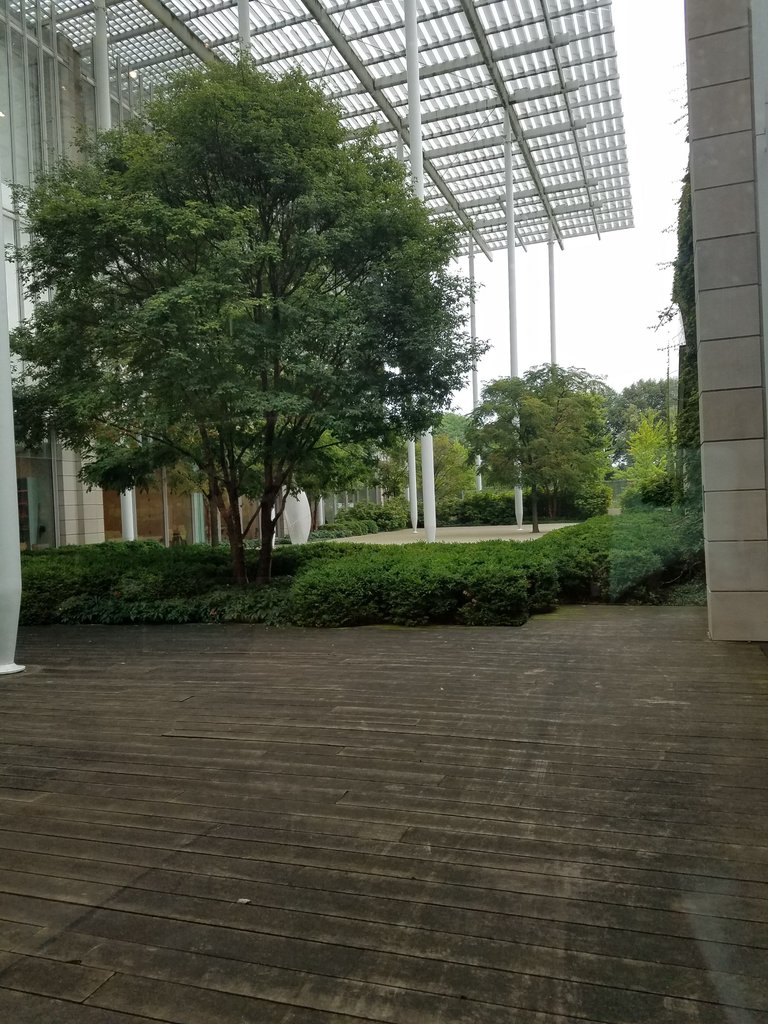

The North Garden:

The Pritzker Garden in the Modern Wing:

The McKinlock Court on the lower level, outside of the Cafe:

View of the Jay Pritzker Pavilion at Millennium Park from the vantage point of the Sculpture Terrace:

EUROPEAN ART

Unfortunately my picture of Vincent van Gogh's Self-Portrait did not turn out.

Two Sisters (On the Terrace), 1881

Oil on canvas

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

French, 1841 – 1919

“He loves everything that is joyous, brilliant, and consoling in life,” an anonymous interviewer once wrote about Pierre-Auguste Renoir. This may explain why Two Sisters (On the Terrace) is one of the most popular paintings in the Art Institute. Here Renoir depicted the radiance of lovely young women on a warm and beautiful day. The older girl, wearing the female boater’s blue flannel, is posed in the center of the evocative landscape backdrop of Chatou, a suburban town where the artist spent much of the spring of 1881. She gazes absently beyond her younger companion, who seems, in a charming visual conceit, to have just dashed into the picture. Technically, the painting is a tour de force: Renoir juxtaposed solid, almost life-size figures against a landscape that—like a stage set—seems a realm of pure vision and fantasy. The sewing basket in the left foreground evokes a palette, holding the bright, pure pigments that the artist mixed, diluted, and altered to create the rest of the painting. Although the girls were not actually sisters, Renoir’s dealer showed the work with this title, along with Acrobats at the Cirque Fernando and others, at the seventh Impressionist exhibition, in 1882.

Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn Memorial Collection

1933.455

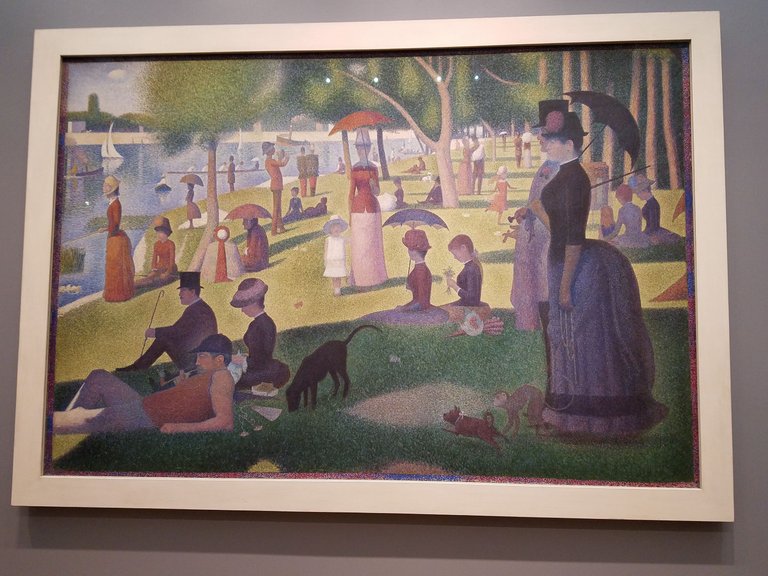

A Sunday on La Grande Jatte — 1884, 1884 / 1886

Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 207.5 × 308.1 cm (81 3/4 × 121 1/4 in.)

Georges Seurat

French, 1859 - 1891

In his best-known and largest painting, Georges Seurat depicted people from different social classes strolling and relaxing in a park just west of Paris on La Grande Jatte, an island in the Seine River. Although he took his subject from modern life, Seurat sought to evoke the sense of timelessness associated with ancient art, especially Egyptian and Greek sculpture. He once wrote, “I want to make modern people, in their essential traits, move about as they do on those friezes, and place them on canvases organized by harmonies of color.”

Seurat painted A Sunday on La Grande Jatte—1884 using pointillism, a highly systematic and scientific technique based on the hypothesis that closely positioned points of pure color mix together in the viewer’s eye. He began work on the canvas in 1884 (and included this date in the title) with a layer of small, horizontal brushstrokes in complementary colors. He next added a series of dots that coalesce into solid and luminous forms when seen from a distance. Sometime before 1889 Seurat added a border of blue, orange, and red dots that provide a visual transition between the painting’s interior and the specially designed white frame, which has been re-created at the Art Institute.

Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection

1926.224

Paris Street; Rainy Day, 1877

Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 212.2 × 276.2 cm (83 1/2 × 108 3/4 in.); Framed: 241.3 × 306.1 × 10.2 cm (95 × 120 1/2 × 4 in.)

Gustave Caillebotte

French, 1848 – 1894

This complex intersection, just minutes away from the Saint-Lazare train station, represents in microcosm the changing urban milieu of late nineteenth-century Paris. Gustave Caillebotte grew up near this district when it was a relatively unsettled hill with narrow, crooked streets. As part of a new city plan designed by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, these streets were relaid and their buildings razed during the artist’s lifetime. In this monumental urban view, which measures almost seven by ten feet and is considered the artist’s masterpiece, Caillebotte strikingly captured a vast, stark modernity, complete with life-size figures strolling in the foreground and wearing the latest fashions. The painting’s highly crafted surface, rigorous perspective, and grand scale pleased Parisian audiences accustomed to the academic aesthetic of the official Salon. On the other hand, its asymmetrical composition, unusually cropped forms, rain-washed mood, and candidly contemporary subject stimulated a more radical sensibility. For these reasons, the painting dominated the celebrated Impressionist exhibition of 1877, largely organized by the artist himself. In many ways, Caillebotte’s frozen poetry of the Parisian bourgeoisie prefigures Georges Seurat’s luminous Sunday on La Grande Jatte—1884, painted less than a decade later.

The Bedroom, 1889

Oil on canvas

Vincent van Gogh

Dutch, 1853 – 1890

Vincent van Gogh so highly esteemed his bedroom painting that he made three distinct versions: the first, now in the collection of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; the second, belonging to the Art Institute of Chicago, painted a year later on the same scale and almost identical; and a third, smaller canvas in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, which he made as a gift for his mother and sister. Van Gogh conceived the first Bedroom in October 1888, a month after he moved into his “Yellow House” in Arles, France. This moment marked the first time the artist had a home of his own, and he had immediately and enthusiastically set about decorating, painting a suite of canvases to fill the walls. Completely exhausted from the effort, he spent two-and-a-half days in bed and was then inspired to create a painting of his bedroom. As he wrote to his brother Theo, “It amused me enormously doing this bare interior. With a simplicity à la Seurat. In flat tints, but coarsely brushed in full impasto, the walls pale lilac, the floor in a broken and faded red, the chairs and the bed chrome yellow, the pillows and the sheet very pale lemon green, the bedspread blood-red, the dressing-table orange, the washbasin blue, the window green. I had wished to express utter repose with all these very different tones.” Although the picture symbolized relaxation and peace to the artist, to our eyes the canvas seems to teem with nervous energy, instability, and turmoil, an effect heightened by the sharply receding perspective.

Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection

1926.417

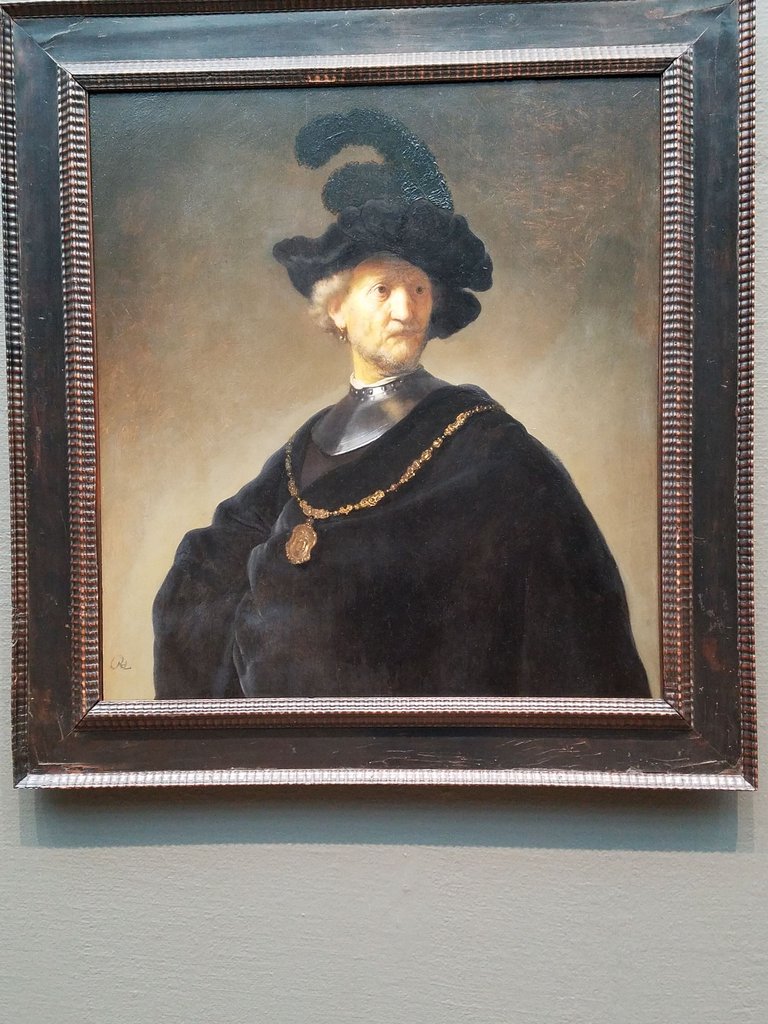

Old Man with a Gold Chain, 1631

Oil on panel

Rembrandt van Rijn

Dutch, 1606 – 1669

This evocative character study is an early example of a type of subject that preoccupied the great Dutch master Rembrandt van Rijn throughout his long career. Although his large output included landscapes, genre paintings, and the occasional still life, he focused on biblical and historical paintings and on portraits. As an extension of these interests, the artist studied the effect of a single figure, made dramatic through the use of costume and rich, subtle lighting. Rembrandt collected costumes to transform his models into characters. Here, the gold chain and steel gorget suggest an honored military career, while the plumed beret evokes an earlier time. The broad black mass of the old man’s torso against a neutral background is a powerful foil for these trappings. The face is that of a real person, weathered and watchful, glowing with pride and humanity. The unidentified sitter, once thought to be the artist’s father, was a favorite model, appearing in many of the artist’s early works. The confident execution suggests that the young Rembrandt completed this picture about 1631, when he had left his native Leiden to pursue a career in the metropolis of Amsterdam; perhaps he wished to use this work to demonstrate his skill in a genre that combined history painting and portraiture.

Mr. and Mrs. W. W. Kimball Collection

1922.4467

The Assumption of the Virgin, 1577 – 1579

Oil on canvas

El Greco (Doménikos Theotokópoulos)

Greek, active in Spain, 1541 – 1614

This painting was the central element of the altarpiece that was El Greco’s first major Spanish commission and first large public work. After living in Venice and Rome, where he absorbed the late Mannerist style, the Greek-born artist settled in the Spanish city of Toledo in 1577 to work on the high altar of the convent church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo. The church of this ancient Cistercian convent was being rebuilt as the funerary chapel of a pious widow, Doña Maria de Silva. In El Greco’s grand design, the Assumption was surmounted by a representation of the Trinity and was flanked by two side altars decorated with paintings of the Adoration of the Shepherds and the Resurrection. The visionary imagery of the Assumption and the Trinity aptly expressed the patron’s hope of salvation. Here the Virgin floats upward, supported on the crescent moon that is symbolic of her purity, while the boldly modeled heads of the crowd of apostles gathered around her empty tomb express amazement and concern. The vigor of El Greco’s broad brushstrokes proclaims the confident achievement of this early work, as does this artist’s large signature in Greek, painted as though affixed to the surface of the picture at the lower right.

Gift of Nancy Atwood Sprague in memory of Albert Arnold Sprague

1906.99

The Feast in the House of Simon, c. 1608 – 1614

Oil on canvas

El Greco (Doménikos Theotokópoulos)

Greek, active in Spain, 1541 – 1614

Workshop of El Greco (Doménikos Theotokópoulos)

Although this painting features the bold highlights, elongated figures, and vibrant colors characteristic of El Greco’s late career, the artist enlisted his workshop to execute some parts of the scene according to his original design. The heads of the figures reflect the work of different artists, probably including the artist’s son, Jorge Manuel, a leader of the workshop in its later years. The fantastical architectural background is unlike any other by El Greco and may have been conceived by an assistant.

Gift of Joseph Winterbotham Collection

1949.397

Christ Taking Leave of his Mother, 1595

Oil on canvas

El Greco (Doménikos Theotokópoulos)

Greek, active in Spain, 1541 – 1614

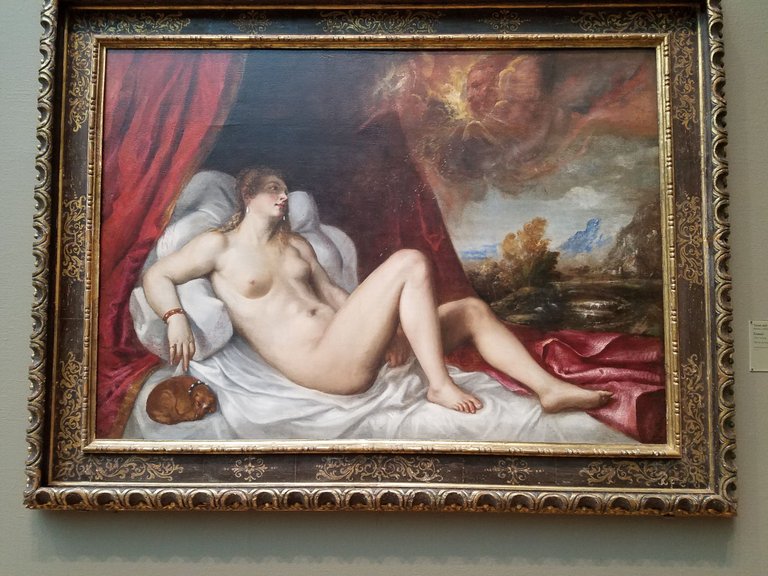

Danae, After 1554

Oil on canvas

Titian and workshop

Italian, 1485 / 1490 - 1576

Extended loan from the Barker Welfare Foundation, New York, NY

9.1973

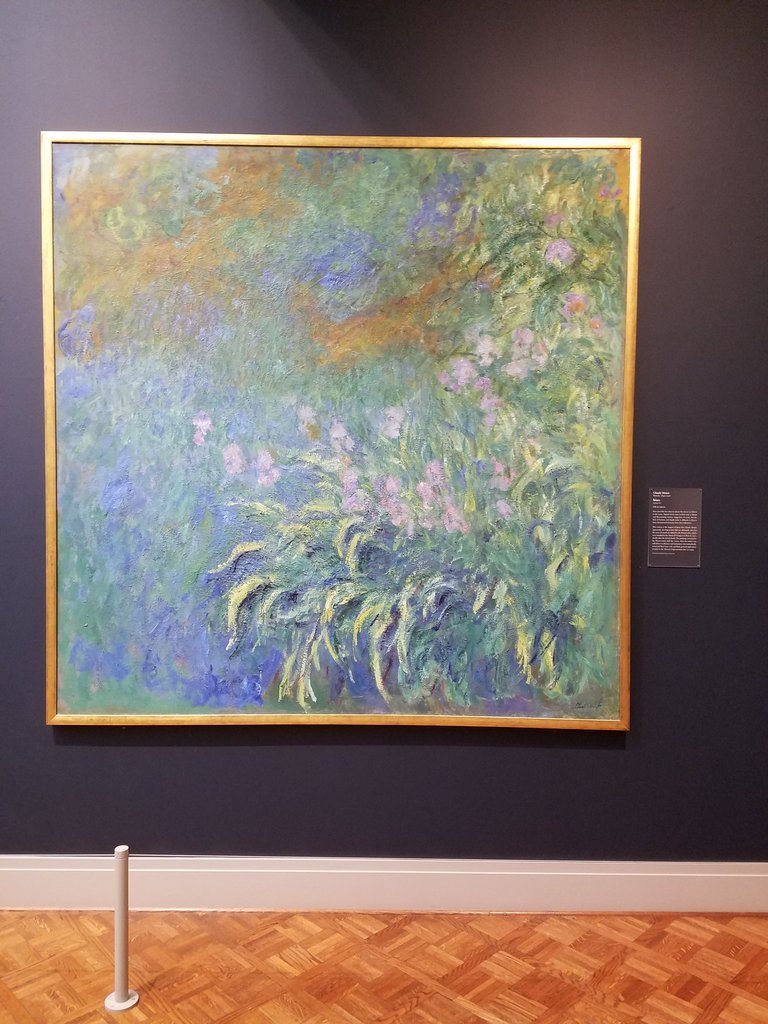

Irises, 1914 / 1917

Oil on canvas

Claude Monet

French, 1840 – 1926

Approximately six and a half feet square, Irises is one of a series of large paintings Claude Monet undertook during World War I experimenting with familiar motifs on an ever-expanding scale. Lacking a discernible horizon or clear sense of depth, the viewer is both on top of and submerged in this encrusted and disorienting surface, suggestive of water, on which various vegetal and floral forms float.

Together with other related canvases, this work remained in the artist’s Giverny studio long after his death in 1926 and was only rediscovered in the 1950s, having suffered localized damage by shrapnel from shells during World War II. In 1956 the Art Institute’s pioneering curator of modern art, Katherine Kuh, bought this painting from Katia Granoff’s gallery in Paris. Kuh recognized a formal affinity between Monet’s late experimental painting and the public’s growing interest in large-scale, abstract works like those by Jackson Pollock, whose Greyed Rainbow entered the Art Institute’s collection in 1955.

Art Institute Purchase Fund

1956.1202

At the Moulin Rouge, 1892 / 1895

Oil on canvas

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

French, 1864 – 1901

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec has been associated with the Moulin Rouge since its opening in 1889: the owner of the legendary nightclub bought the artist’s Equestrienne as a decoration for the foyer. Toulouse-Lautrec populated At the Moulin Rouge with portraits of the legendary nightclub’s regulars, including himself—the diminutive figure in the center background—accompanied by his cousin, physician Gabriel Tapié de Céleyran. Dancer La Goulue arranges her hair behind the table where Jane Avril, another famous performer, socializes. Singer May Milton peers out from the right edge of the painting, her face harshly lit and acid green. At some point, the artist or his dealer cut down the canvas to remove Milton, perhaps because her strange appearance made the work hard to sell. Whatever the reason, by 1914 the cut section had been reattached to the painting.

Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection

1928.610

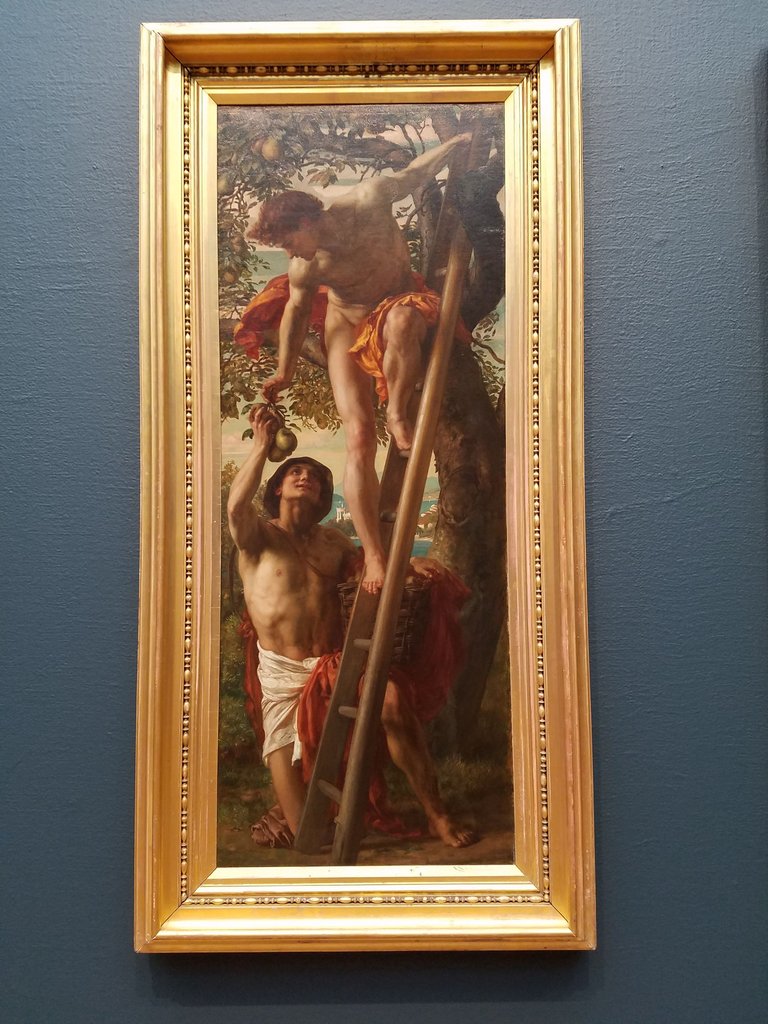

The Golden Age, 1875

Oil on canvas

Sir Edward John Poynter

British, 1836 – 1919

Bequest of Suzette Morton Davidson

2002.379

The Festival, 1875

Oil on canvas

Sir Edward John Poynter

British, 1836 – 1919

Bequest of Suzette Morton Davidson

2002.380

Hercules and the Lernaean Hydra, 1875 / 1876

Oil on canvas

Gustave Moreau

French, 1826 - 1898

Gustave Moreau developed a highly personal vision that combined history, myth, mysticism, and a fascination with the exotic and bizarre. Rooted in the Romantic tradition, Moreau focused on the expression of timeless enigmas of human existence rather than on recording or capturing the realities of the material world.

Long fascinated with the myth of Hercules, Moreau gave his fertile imagination free rein in Hercules and the Lernaean Hydra. Looming above an almost primordial ooze of brown paint is the seven-headed Hydra, a serpentine monster whose dead and dying victims lie strewn about a swampy ground. Calm and youthful, Hercules stands amid the carnage, weapon in hand, ready to sever the Hydra’s seventh, “immortal” head, which he will later bury.

Despite the violence of the subject, the painting seems eerily still, almost frozen. Reinforcing this mysterious quality is Moreau’s ability to combine suggestive, painterly passages with obsessive detail. The precision of his draftsmanship and the otherworldliness of his palette are the result of his painstaking methods; he executed numerous preliminary studies for every detail in the composition. In contrast to such exactitude, the artist also made bold, colorful watercolors that eschew detail, as exercises to resolve issues of composition and lighting.

Moreau seems to have intended this mythological painting to express contemporary political concerns. He was profoundly affected by France’s humiliating military defeat by Prussia in 1870–71. Whether or not Hercules literally personifies France and the Hydra represents Prussia, this monumental work portrays a moral battle between the forces of good and evil, and of light and darkness, with intensity and power.

Gift of Mrs. Eugene A. Davidson

1964.231

Apollo and Marsyas, 1888

Oil on board

Hans Thoma

German, 1839 – 1924

Along with Arnold Böcklin, Hans Thoma was a leading Northern European figure in the shift from Realism and history painting to art inspired by classical myths and legends. Taken from Ovid’s epic poem Metamorphoses, Thoma showed the satyr Marsyas challenging Apollo, the master of the lyre, to a musical contest. Although he avoided depicting the cruel outcome of the match (the satyr lost and was flayed alive by Apollo), the artist’s treatment of Apollo, whose idealized body and luminous skin set him apart from the shadowy halftones of his challenger, hints at the winner. Thoma’s painted frame may also have been inspired by a tale from Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Through prior gift of Henry Morgen, Ann G. Morgen, Meyer Wasser, and Ruth G. Wasser

2008.555

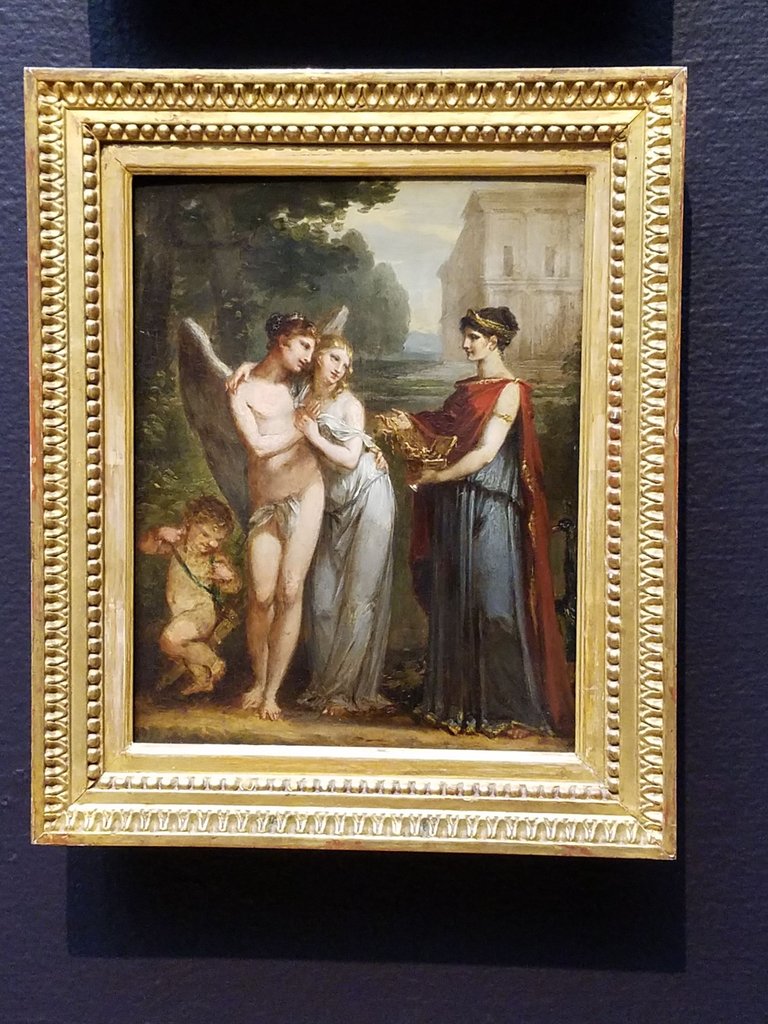

Innocence Prefers Love to Riches, c. 1804

Oil on panel

Pierre Paul Prud’hon

French, 1758 – 1823

In this allegorical painting, a personification of Innocence at center signals her preference for Love, represented as a cupid, over Riches, taking the form of a woman in lavish Grecian robes and offering a chest of golden baubles. Pierre-Paul Prud’hon complicated this straightforward parable by manipulating the figures’ postures: while Innocence embraces Love, she gazes longingly over her shoulder at Riches, inviting viewers to wonder about the finality of her decision.

Prud’hon created this preparatory sketch for a larger painting to be completed by his collaborator and friend, Constance Mayer, who was known for her portraits and allegorical scenes.

Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection

1933.1090

Judith, c. 1540

Oil on panel

Jan Sanders van Hemessen

Netherlandish, active c. 1519 – 1556

Judith was considered one of the most heroic women of the Old Testament. According to the biblical story, when her city was besieged by the Assyrian army, the beautiful young widow gained access to the quarters of the general Holofernes. After winning his confidence and getting him drunk, she took his sword and cut off his head, thereby saving the Jewish people. Although Judith was often shown richly and exotically clothed, Jan Sanders van Hemessen chose to present her as a monumental nude, aggressively brandishing her sword even after severing Holofernes’s head.

Van Hemessen was one of the chief proponents of a style, popular in the Netherlands in the first half of the sixteenth century, that was deeply indebted to the monumental character of classical sculpture, as well as to the art of Michelangelo Buonarroti and Raphael. Judith’s muscular body and her elaborate, twisting pose reflect these influences. Yet the use of the aggressive nude figure here also suggests a certain ambivalence on the part of the artist and his audience toward the seductive wiles Judith may have employed to disarm Holofernes. In this work, Van Hemessen combined an idealized form with precisely rendered textures, as in the hair and beard of Holofernes and Judith’s gauzy headdress and brocaded bag. The interplay between the straining pose of the figure, the dramatic lighting, and the fastidiously recorded surfaces serves to heighten the tension of this composition.

Wirt D. Walker Fund

1956.1109

The Eruption of Vesuvius, 1771

Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 116.8 × 242.9 cm (46 × 95 5/8 in.)

Pierre-Jacques Volaire

French, 1729 – after 1799

In this imposing composition, molten lava spews from the mouth of Mount Vesuvius in Italy and winds down the hillside towards the Bay of Naples. Energetic human figures observe the spectacle, their small scale emphasizing the volcano’s enormity.

Vesuvius erupted six times between 1707 and 1794 and thus became a touchstone of popular culture at the time. This same period saw the first systematic excavations of Pompeii, the ancient city that Vesuvius famously destroyed in 79 CE. The romance of Vesuvius simultaneously wondrous and terrifying, ancient and contemporary—made it a frequent subject in 18th-century European art and literature. Paintings like this had enormous appeal in tourist markets.

Charles H. and Mary F. S. Worcester Collection

1978.426

Alexander at the Tomb of Cyrus the Great, 1796

Oil on canvas

Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes

French, 1750 - 1819

This landscape and its companion piece, Mount Athos Carved as a Monument to Alexander the Great, reflect the late-18th-century enthusiasm for the antique, as well as the cult of sensibility that made the tomb in a landscape a favored subject for art in this period. Here Alexander, who overthrew the Persian Empire, arrives at the tomb of its founder, Cyrus the Great (590/580–c. 529 B.C.), only to find that it has been desecrated. In choosing the subjects of this pair of moralizing landscapes, Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes was doubtless suggesting the transitory nature of empire and of life itself.

Purchased with funds provided by Mrs. Harold T. Martin

1983.35

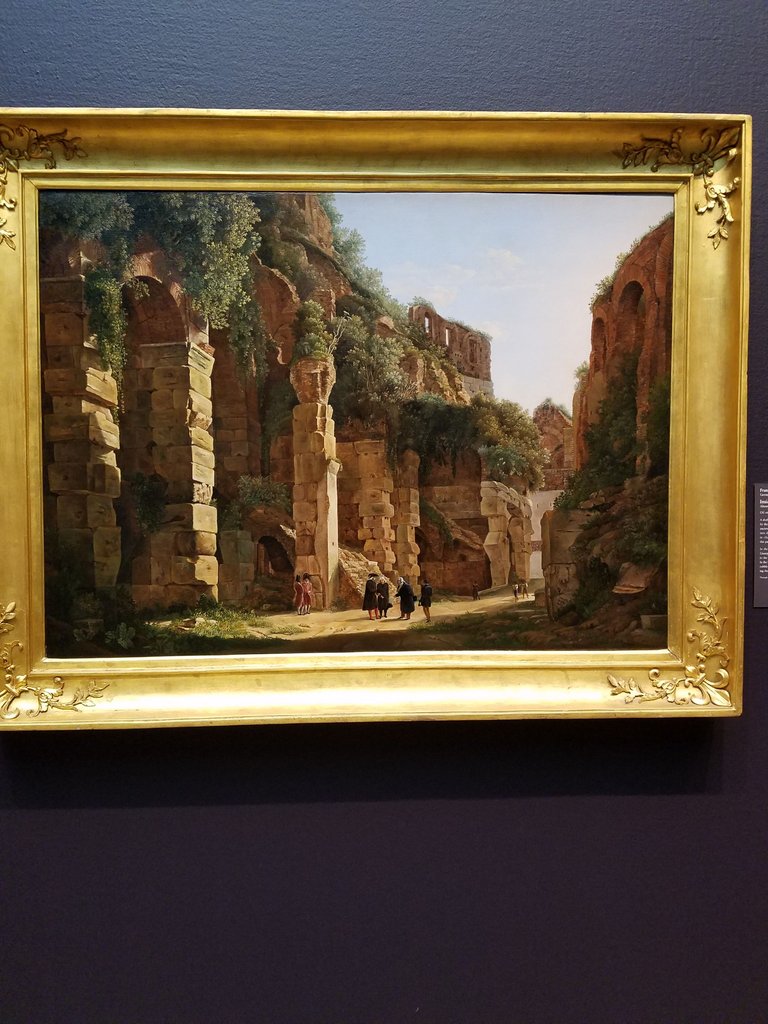

Inside the Colosseum, c. 1823

Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 100.4 × 137.5 cm (39 1/2 × 58 1/4 in.); Framed: 125 × 161 cm (49 × 63 in.)

Franz Ludwig Catel

German, 1778 – 1856

A shaft of sunlight illuminates a group of figures dwarfed by the monumental architecture of the Colosseum, the ancient amphitheater in Rome. The building had fallen into disrepair for centuries until restorations began in 1822, the year before Franz Ludwig Catel made this painting.

In the foreground, a figure identifiable as architect Giuseppe Valadier bows slightly while presenting plans to the red-stockinged Cardinal Ercole Consalvi at left. In the background, two workers carry a sack filled with rubble from the Colosseum’s depths, visually representing the labor involved in the project.

Through prior gift of Mr. and Mrs. Chauncey B. Borland

2013.1094

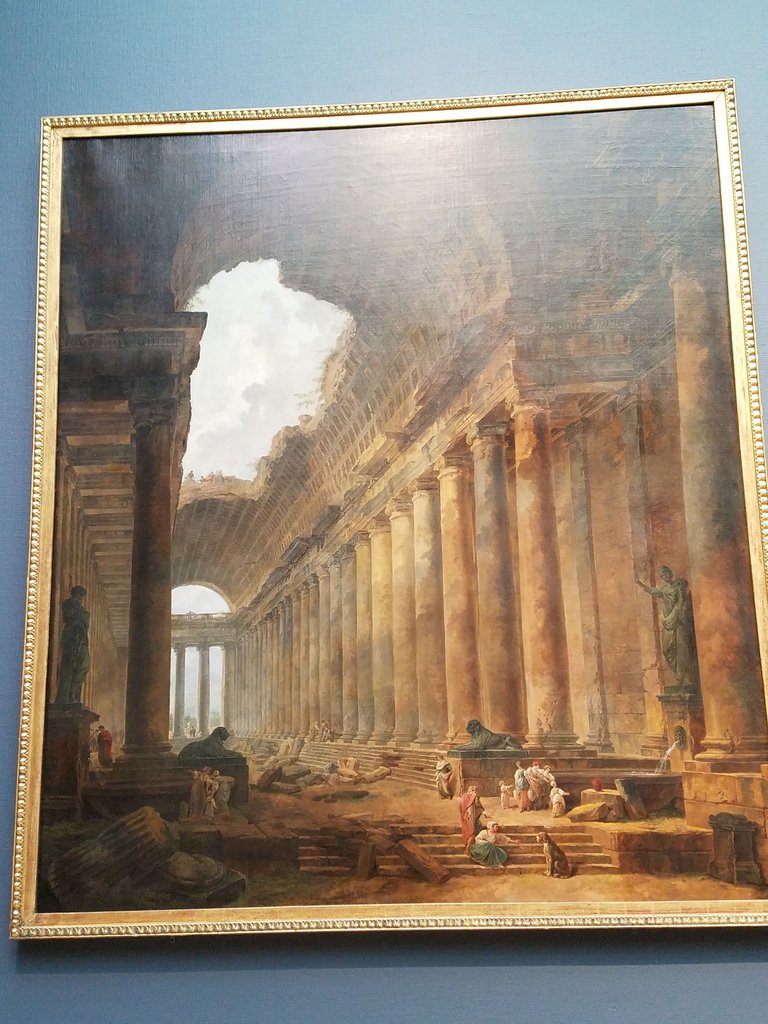

The Fountains, 1787 / 1788

Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 255.3 × 221.2 cm (100 1/2 × 88 1/8 in.); Framed: 265.5 × 233.4 cm (104 1/2 × 91 7/8 in.)

Hubert Robert

French, 1733 - 1808

The painting of Classical ruins had reached the zenith of its popularity when Hubert Robert, the leading French practitioner of this specialty, was commissioned in 1787 to paint a suite of four canvases for a wealthy financier’s château at Méréville, near Paris. The Fountains and its companion pieces were set into the paneled walls of a salon in the château, creating an alternate space that played off of the elegant, Neoclassical decor of the room. Robert has studied in Rome from 1754 to 1765 and there had gleaned his artistic vocabulary. Like the other three large paintings from the group painted for Méréville, all in the Art Institute, The Fountains exploits Robert’s typical vocabulary of fictive niches, arches, coffered vaults, colonnades, majestic stairwells, and Roman statuary to create a fantasy of expansive space. The four paintings are inhabited by tiny figures in the foreground; these serve only to set the scale and animate the scene, for the ruins themselves are the true subject of the pictures. In his use of ruins, Robert embodied the notion of the relationship of mankind and the built environment to nature that was expressed by the French philosopher and encyclopedist Denis Diderot: “Everything vanishes, everything dies, only time endures.”

Gift of William G. Hibbard

1900.385

The Old Temple, 1787 / 1788

Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 255 × 223.2 cm (100 3/8 × 87 7/8 in.); Framed: 265.5 × 233.4 cm (104 1/2 × 91 7/8 in.)

Hubert Robert

French, 1733 - 1808

The four large canvases by Hubert Robert in the Art Institute’s collection were commissioned by wealthy financier Jean-Joseph, Marquis de Laborde, to decorate a salon in his château at Méréville, France. Installed on all sides of the room, they would have suggested that the walls had dissolved, revealing fantasies of Classical architecture animated by scenes of everyday life. Robert was much sought after as a painter of architectural ruins, a genre that appealed to the late 18th-century taste for the antique. He cultivated his knowledge of antiquity over more than a decade of travel and study in Italy.

Gift of Adolphus C. Bartlett

1900.382

The Obelisk, 1787 / 1788

Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 255.6 × 223.5 cm (100 7/8 × 88 in.); Framed: 265.5 × 233.4 cm (104 1/2 × 91 7/8 in.)

Hubert Robert

French, 1733 - 1808

This painting is one of four depictions of architectural fantasies by Hubert Robert commissioned by the Marquis de Laborde for his elegant country estate at Méréville, south of Paris. It features a grandiose vaulted space that frames an obelisk, with a peristyle, or colonnade, closing off the distance. Through years of study in Italy, Robert absorbed the vocabulary of Classical architecture and sculpture into his own imaginative language. Here, the female figure in the central niche is based on a first-century sculpture that the artist would have seen during his stay in Rome.

Gift of Clarence Buckingham

1900.383

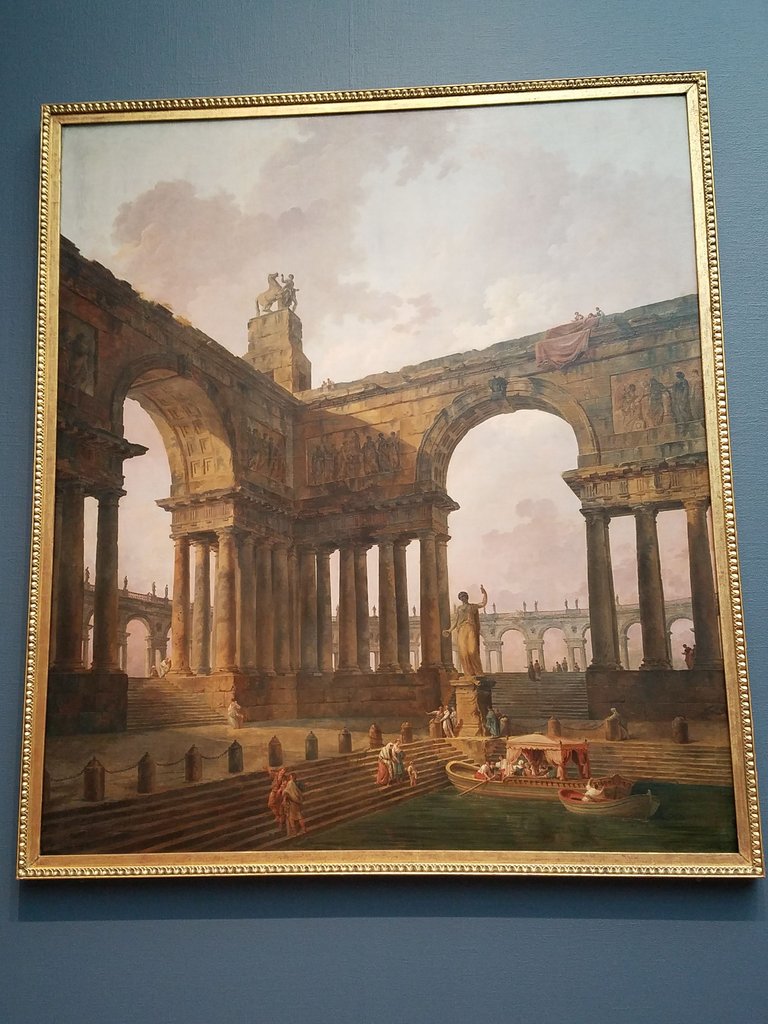

The Landing Place, 1787 / 1788

Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 255 × 222.9 cm (100 7/8 × 87 3/4 in.); Framed: 265.5 × 233.4 cm (104 1/2 × 91 7/8 in.)

Hubert Robert

French, 1733 - 1808

The Landing Place is one of four works commissioned to decorate a salon in the château of Jean-Joseph, Marquis de Laborde, a successful financier. This view is dominated by an immense colonnade, in front of which several people are shown departing in a pleasure boat while others linger at the water’s edge. As he constructed this fantasy, Hubert Robert included direct references to renowned antique monuments, combining them with elements of his own invention. The perspective and scale of Robert’s four painted architectural fantasies were coordinated with the proportions of the room to give the illusion of a vast, open space.

Gift of Richard T. Crane

1900.384

Portrait of Don Juan of Austria, 1559 / 1560

Oil on panel, transferred to canvas

Alonso Sánchez Coello

Spanish, 1531 / 1532 – 1588

Max and Leola Epstein Collection

1954.293

John of Austria (24 February 1547 – 1 October 1578) was the illegitimate son of Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. John was recognized in Charles V's will. He later served his half-brother, King Philip II of Spain. Pope Pius V named John as the supreme commander of the Holy League fleet and John led his forces to a pivotal victory against the Ottoman Turks during the Battle of Lepanto.

Study of a Young Woman, About 1770

Oil on canvas

Jean-Baptiste Greuze

French, 1725 - 1805

The elegant young woman in this intimate painting looks directly at the viewer with one hand raised delicately to her chin, as if she has just been called to attention. Her features were likely drawn from a studio model rather than a sitter for a commissioned portrait. Artists made such works - called expressive heads, or tetes d'expression - to demonstrate their skill at representing emotion. Jean-Baptiste Greuze's tetes d'expression were a source of the artist's tremendous popularity during his lifetime.

Private collection

Obj. 269209

Rêverie (Portrait of Gabrielle Borreau), 1862

Oil on paper, mounted on canvas

Gustave Courbet

French, 1819 – 1877

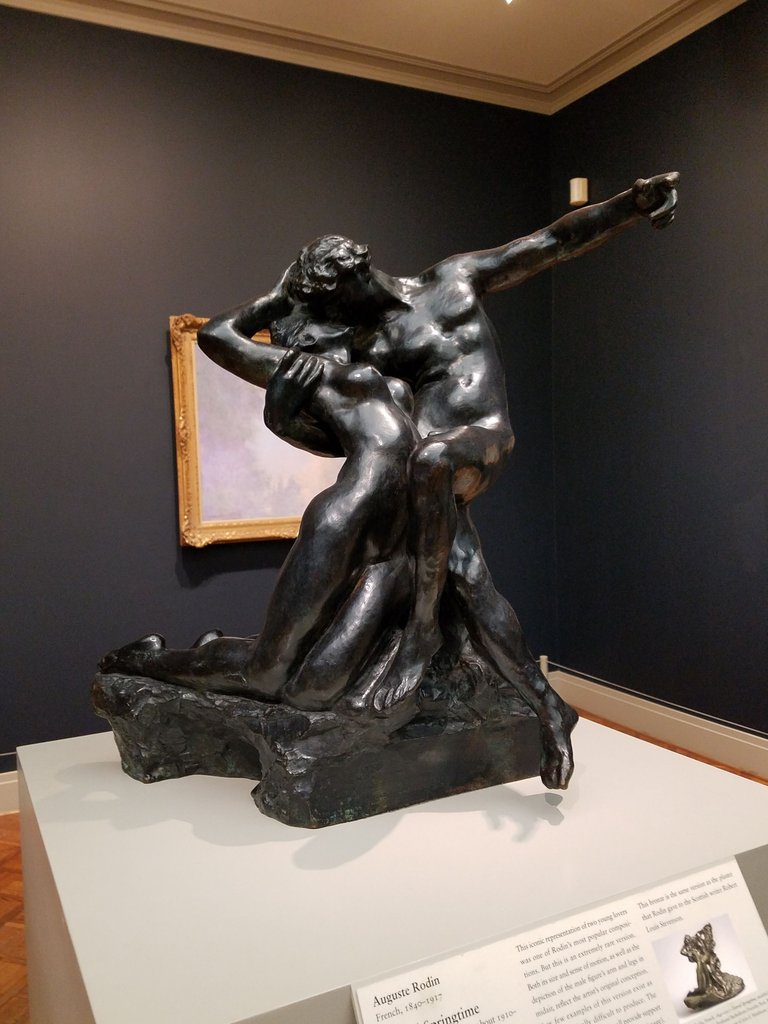

Eternal Springtime, Modeled about 1884, cast about 1910 - mid-1920s

Bronze

Auguste Rodin

French, 1840 - 1917

Alexis Rudier Foundry, Paris

On loan from a private collection

This iconic representation of two young lovers was one of Rodin's most popular compositions. But this is an extremely rare version. Both its size and sense of motion, as well as the depiction of the male figure's arm and legs in midair, reflect the artist's original conception. Very few examples of this version exist as it was technically difficult to produce. The hundreds of later examples all provide support for the male figure's arm and legs. This bronze is the same version as the plaster that Rodin gave to the Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson.

Bust of Diana, about 1692 – 1693

Marble

Giuseppe Mazza

Italian, 1653 — 1741

Around 1692 the Bolognese sculptor Giuseppe Mazza carved a series of at least three half-length figures for the interior of the Liechtenstein Palace in Vienna. The subjects, taken from Greek mythology, included the musician and poet Orpheus, the hero Meleager, and the goddess Diana, identified here by the crescent moon that adorns her forehead. The compact pose of the figure and lack of carving on the reverse side indicate that this sculpture was intended to be placed against a wall or within a niche.

Harry and Maribel G. Blum Endowment

1988.277

Roger and Angelica Mounted on the Hippogriff, modeled c. 1840 (cast c. 1884)

Bronze

Antoine Louis Barye

French, 1795 - 1875

This bronze depicts a scene from Orlando Furioso, a chivalric epic from the Italian Renaissance that inspired artists well into the 19th century. In it, Roger, a knight, rides a hippogriff to save Princess Angelica, who has been chained to a rock to be devoured by a sea monster. Antoine Louis Barye captured the moment the heroes take flight, leaving behind the defeated monster with waves lapping around it. This sculptural group formed part of a decorative ensemble for a fireplace mantel, which was commissioned around 1840 by Antoine, Duke of Montpensier, the youngest son of King Louis Philippe of France. The composition was recast frequently during and after Barye’s lifetime.

George F. Harding Collection

1984.34

Bust of a Woman, 1851

Bronze

Charles Henri Joseph Cordier

French, 1827 – 1905

Cast by Eck et Durand Fondeur

French, 19th century

This fictionalized portrayal is a companion piece to the Bust of Saïd Abdullah. Charles-Henri-Joseph Cordier initially titled this stylized and highly detailed sculpture Vénus africaine (African Venus), thus conflating the ancient Greek goddess of love and beauty with his rendering of a Black woman. Her parted lips and bare shoulders and chest evoke the erotic associations of her former namesake deity, while the draping of her costume suggests Classical refinement.

In 1851 the anthropological gallery of the National History Museum in Paris commissioned casts of this work and the likeness of Abdullah. Cordier’s ethnographic busts reflect mid-19th-century discourse on aesthetics and colonization as well as pseudoscientific theories of race.

Ada Turnbull Hertle Fund

1963.840

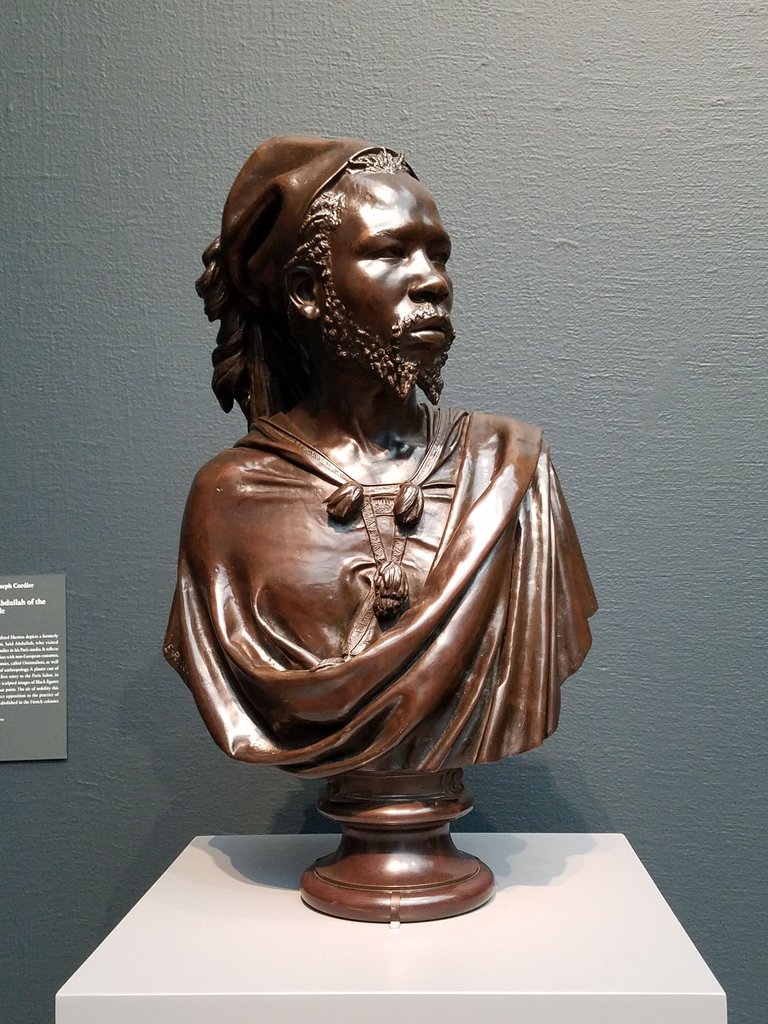

Bust of Saïd Abdullah of the Darfour People, 1848

Bronze

Charles Henri Joseph Cordier

French, 1827 – 1905

Cast by Eck et Durand Fondeur

French, 19th century

This naturalistic yet idealized likeness depicts a formerly enslaved Sudanese man, Saïd Abdullah, who visited Charles-Henri-Joseph Cordier in his Paris studio. It reflects the 19th-century fascination with non-European costumes, customs, and physiognomies, called Orientalism, as well as the burgeoning field of anthropology. A plaster cast of this bust was Cordier’s first entry to the Paris Salon, in 1848, and one of the few sculpted images of Black figures shown publicly up to that point. The air of nobility this figure projects may reflect opposition to the practice of slavery, which had been abolished in the French colonies that same year.

Ada Turnbull Hertle Fund

1963.839

Chimera, 1869

Enamel on copper

Alexandre Frederic Charlot de Courcy

French, 1832 – 1886

After Gustave Moreau

French, 1826 – 1898

This sumptuously colored, circular plaque depicts a chimera, a mythical hybrid of multiple animals, launching into the air from a rocky precipice with a nude woman clinging to him. It is the earliest and largest surviving product of the five-year collaboration between painter Gustave Moreau and enameler Frédéric Charlot de Courcy. In enamel painting, vitreous powders are mixed with a volatile oil, painted onto a metal support, and fired in a kiln. Artists, collectors, and critics admired the material’s jewel-like surfaces, bright colors, and ability to appear variably translucent and opaque.

Purchased with funds provided by Constance T. and Donald W. Patterson

2024.88

Ad Astra, 1894 / 96

Oil on canvas with a painted and gilded wooden shrine

Akseli Gallen-Kallela

Finnish, 1865 – 1931

After associating with the Symbolists, including Edvard Munch, in Paris, Akseli Gallen-Kallela carried these influences to his native Finland while also incorporating indigenous folkloric traditions into his artistic practice. By intermingling Nordic Neo-Romanticism, Symbolism, and the decorative arts, he created a new visual language, which both spoke to and espoused the burgeoning sense of Finnish identity in the late 19th century. This conception of a unique ethnic culture reflected a general resistance within Finland to the dominance of Russia, which had conquered the country in 1809, as well as the rise of nationalist movements throughout Europe during this time.

The artist produced Ad astra (To the Stars) in rural Finland. He later built a wilderness studio and home there and this work decorated the space. Gallen-Kallela saw the girl’s pose as recalling Christ’s Crucifixion. The suspension of gravity, as indicated by her hair, and the upward momentum evoke the triumph of the Resurrection. The frame, which he both designed and executed, was fashioned to resemble an altarpiece, and he employed the painting as one during his daughter’s baptism.

2017.133

Pelican, c. 1896

Glazed stoneware

Emmanuel Fremiet

French, 1824 – 1910

Made by Émile Muller et Cie, Ivry-sur-Seine, France, 1854 –1908

Paul H. Leffmann Fund

2018.369

Personally, I think this Chthonic pelican reminds me of H.P. Lovecraft....

MEDIEVAL & RENAISSANCE

Saint George and the Dragon, 1434 / 1435

Tempera on panel

Bernat Martorell

Spanish, about 1400 – 1452

Bernat Martorell was the greatest painter of the first half of the fifteenth century in Catalonia in northeastern Spain. Depicted here is the most frequently represented episode from the popular legend of Saint George, in which the model Christian knight saves a town and rescues a beautiful princess. Conceived in the elegant, decorative International Gothic style, the painting was originally the center of an altarpiece dedicated to Saint George that was apparently made for the chapel of the palace of the Catalan government in Barcelona. This central scene was surrounded by four smaller narrative panels, now in the Musée du Louvre, Paris, and was probably surmounted by a lost image of Christ on the Cross. Here Saint George, on his white steed, triumphs over the evil dragon. A wealth of precisely observed details intensifies the drama. Dressed in an ermine-lined robe, the princess wears a sumptuous gilt crown atop her wavy red-gold hair. Her parents and their subjects watch the spectacle from the distant town walls. George’s halo and armor and the scaly body of the dragon are richly modeled with raised stucco decoration. Martorell also treated the ground, littered with bones and crawling with lizards, in a lively manner, giving it a gritty texture.

Gift of Mrs. Richard E. Danielson and Mrs. Chauncey McCormick

1933.786

Retable and Frontal of the Life of Christ and the Virgin Made for Pedro López de Ayala, 1396

Tempera and gold on panel

Dimensions: Retable: 257 × 669.9 cm (99 3/4 × 263 3/4 in.); Frontal: 108 × 291.2 cm (42 7/16 × 114 5/8 in.)

Spanish

This remarkable ensemble is made up of a retable, which was set up behind the altar table, and a frontal, which decorated the front of the table itself. The work is literally a testament to the piety of Pedro López de Ayala, a major figure in the political and cultural life of late medieval Spain. He was a courtier, soldier, and diplomat in the service of the kings of Castile, eventually serving as chancellor; he also wrote poetry, a treatise on hunting, and important chronicles of his era.

Ayala expected his altarpiece to be a perpetual plea for his eternal salvation and that of his family. Indeed, for more than five hundred years, it decorated the family’s funerary chapel in their fortified palace in northern Spain. Ayala was careful to declare his donation of the altarpiece in honor of Christ and the Virgin Mary through the inscription that runs across the bottom margin; the images of himself and his wife, Leonora de Guzman, kneeling in prayer with their son and daughter-in-law at either end of the lower register; and their coats of arms — two wolves and two cauldrons — alternating around the frames.

The massive altarpiece must have been constructed and painted inside the small chapel. To accomplish this, Ayala called upon local artists, who created a series of scenes that tell the stories of the life of Christ and the Virgin and center on images of the Crucifixion and of an empty throne that probably once framed a statue of the Virgin and Child. These scenes are not projections of convincing pictorial space. Rather, with their plain backgrounds and framing arcades, they hark back to earlier architectural decoration and manuscript illumination. The altarpiece was clearly intended to impress through its monumental scale, its narrative clarity, and its costly materials, which include gold and silver leaf and glazes of rare and expensive ultramarine blue.

Gift of Charles Deering

1928.817

Adoration of the Shepherds, About 1520

Glazed terra-cotta

Benedetto Buglioni and workshop

Italian, 1459 / 1460 – 1520

Gift of Kate S. Buckingham, Lucy Maud Buckingham Memorial Collection

1924.218

The Assumption of the Virgin with Saints from an Augustinian altarpiece, 1450 / 1475

Tempera and oil on panel

Italian, Venice

George F. Harding Collection

1984.24d

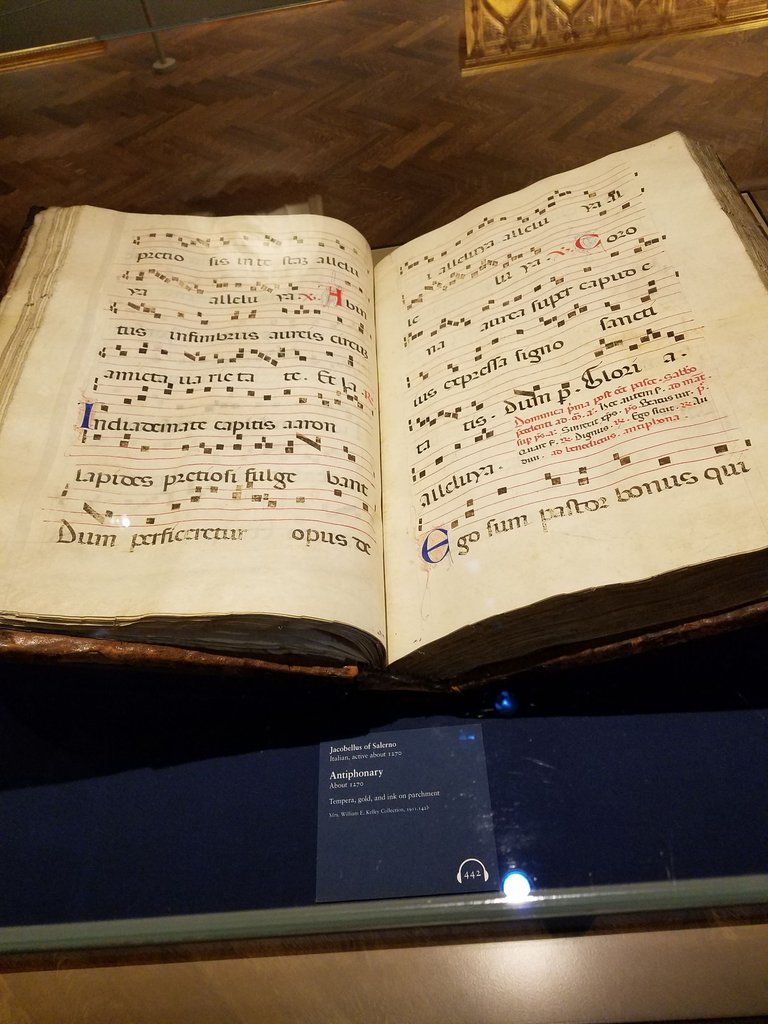

Antiphonary, About 1270

Tempera, gold, and ink on parchment

Jacobellus of Salerno

Italian, active about 1270

Mrs. William E. Kelley Collection

1911.142b

An antiphonary is a religious liturgical book containing the sung portions of the Divine Office.

ARMS & ARMOR

Field Armor for Man, c. 1520

Steel, iron, brass, leather, and textile

South German, Nuremberg

Skillfully forged of steel, this composite armor achieves its beauty with the simple elegance of its austere lines and form rather than its surface decoration. The armor was expertly crafted for protection: the smooth, rounded shape, breastplate with a pronounced vertical ridge down the center, and heavy roping (turned edge etched with lines) at the upper edge of the breastplate functioned to deflect sword thrusts and glancing blows. Thick roping on the gauntlet knuckles acted as added protection. The helmet, with its smooth, rounded form, was shaped to deflect downward blows away from the head. The bracket attached to the right breastplate is called the lance rest, a shock-absorbing support designed to hold the lance when it was couched under the right armpit.

George F. Harding Collection

1982.2401a-g

Cleopatra and Antony Enjoying Supper, from The Story of Caesar and Cleopatra, c. 1680

Wool and silk, slit and double interlocking tapestry weave

After a design by Justus van Egmont

Flemish, 1601 – 1674

Woven at the workshop of Gerard Peemans

Flemish, 1637 / 1639 – 1725

Brussels, Flanders (now Belgium)

To impress Antony, Cleopatra promised to organize the most lavish supper he had ever attended. The meal itself was ordinary, but at its end, Cleopatra dissolved a pearl in a cup of vinegar and drank it. This event was not recorded by Plutarch; it derives from Pliny’s Natural History (1st century A.D.).

Gift of Mrs. Chauncey McCormick and Mrs. Richard Ely Danielson

1944.17

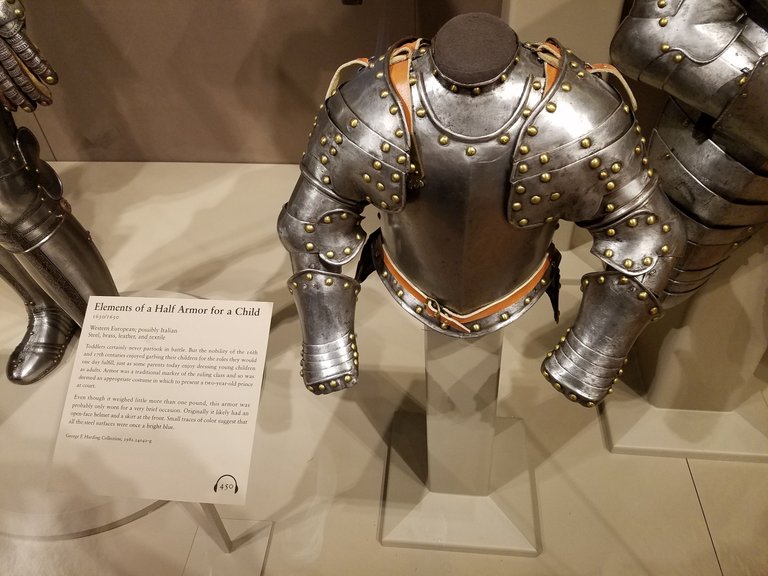

Elements of a Half Armor for a Child, 1630 / 1650

Steel, brass, leather, and textile

Western European; possibly Italian

Toddlers certainly never partook in battle. But the nobility of the 16th and 17th centuries enjoyed garbing their children for the roles they would one day fulfill, just as some parents today enjoy dressing young children as adults. Armor was a traditional marker of the ruling class and so was deemed an appropriate costume in which to present a two-year-old prince at court.

Even though it weighed little more than one pound, this armor was probably only worn for a very brief occasion. Originally it likely had an open-face helmet and a skirt at the front. Small traces of color suggest that all the steel surfaces were once a bright blue.

George F. Harding Collection

1982.24042-g

Dress Sword, 1743

Gold-Copper alloy, steel, and gilding

Hilt: Portuguese or Spanish; blade: probably German

Cast in solid gold, the hilt of this dress sword is a rare survival. More often such extravagant pieces were melted down for the value of the precious material. The goldsmith who made it is unknown, though the heavy florid style and form of the guard suggests a southern European, perhaps Portuguese origin.

George F. Harding Collection

1982.2153

Another sword:

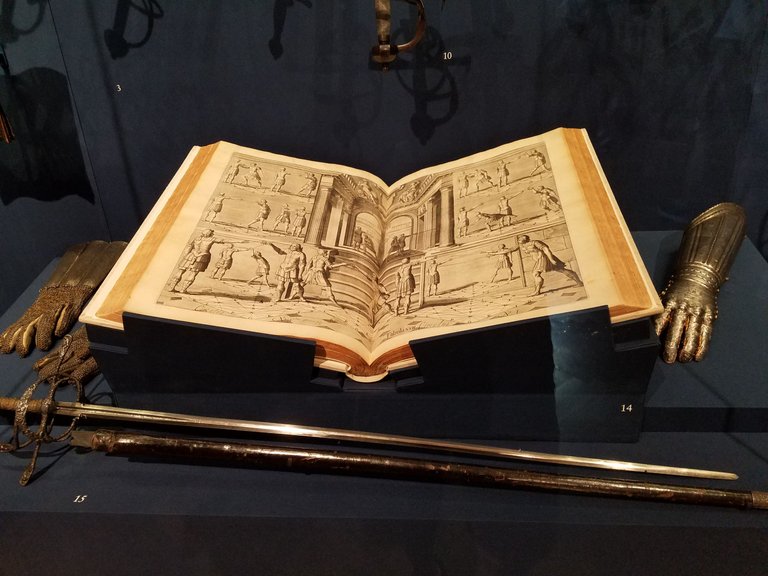

The Academy of the Sword, 1630

Engraving and letterpress on laid paper

Author: Girard Thibualt

Flemish, about 1574 - 1627

Leiden

One of the most extravagantly illustrated works of its time, The Academy of the Sword is a step-by-step guide to fencing. It was made for members of the nobility and other wealthy people seeking instruction in the art of self-defense.

George F. Harding Collection, Ryerson Library

ARTS OF THE GREEK, ROMAN, AND BYZANTINE WORLDS

A Copy of Ten Marble Fragments of the Great Eleusinian Relief, 2017

Machined aluminum

Charles Ray

American, born 1953

This relief made from machined aluminum was inspired by an ancient Roman marble relief that is itself a copy of an ancient Greek relief carved in the 5th century BCE. This contemporary "copy of a copy" is the work of Chicago-born, Los Angeles-based artist Charles Ray, who has pushed the boundaries of sculpture practice since the early 1980s. The original Greek relief was created for the site of Eleusis, home to a famous sanctuary and mystery cult that honored the mother-daughter goddesses Demeter and Persephone. Placed here amidst the art of the ancient Mediterranean, Ray's relief engages with a lineage of reinterpretation while also demonstrating the importance of Eleusis throughout history.

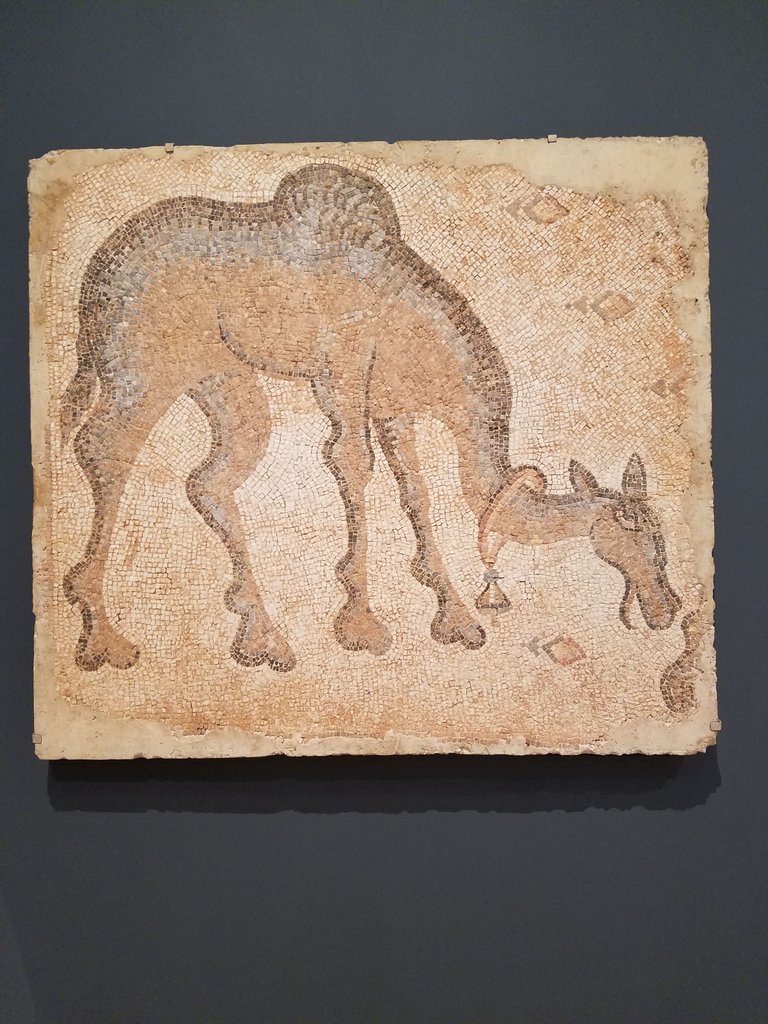

Mosaic Fragment with Grazing Camel, 5th century

Stone in mortar

Byzantine; Eastern Mediterranean, probably Syria

This image of a grazing camel probably came from a larger composition with other animals that decorated the floor of a semipublic space within a private home, such as a reception or dining room. This animal is represented against a white ground decorated with florets. A bell hangs from the camel’s neck as it reaches toward an object, perhaps a vessel filled with water, at the lower right. The knobby contours of the camel’s body are accentuated by areas of shading in subtly modulated colors, including black, brown, brick red, and olive green.

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert B. Mayer

1970.1065

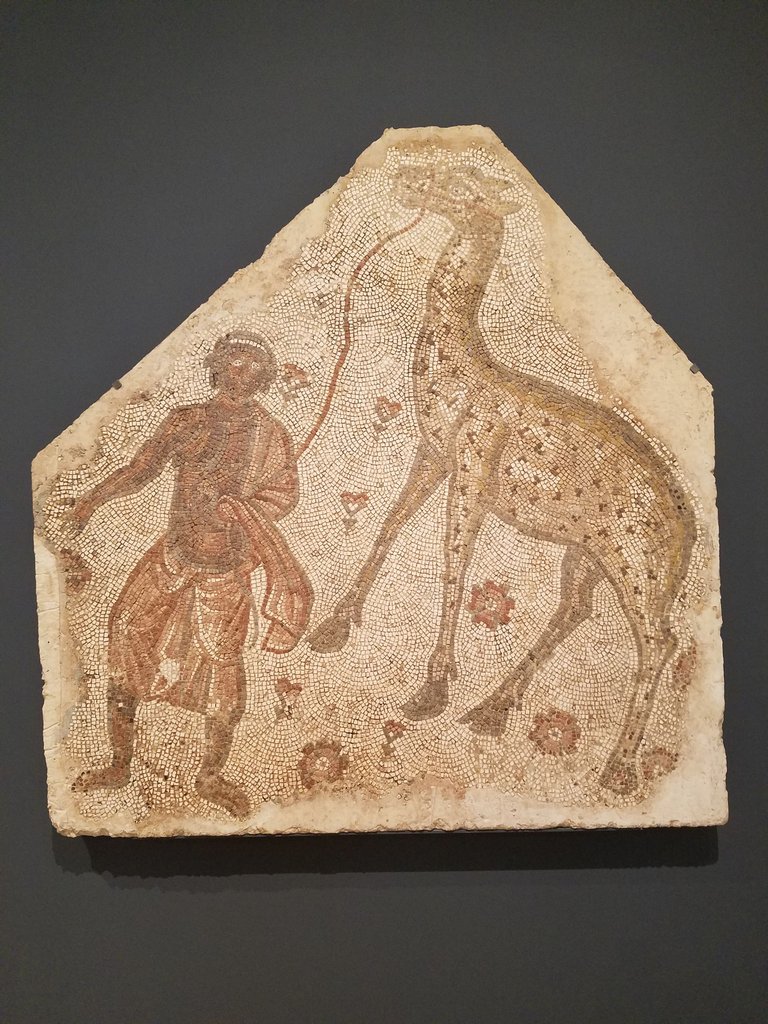

Mosaic Fragment with Man Leading a Giraffe, 5th century

Stone in mortar

Byzantine; Syria or Lebanon

This mosaic fragment was once part of a larger composition that paved the floor of a wealthy family villa in the Eastern Mediterranean. Composed of thousands of small tesserae, or stone cubes, it shows a giraffe and a human handler standing against a decorative backdrop of scallop-shaped semicircles. No doubt originally set amid a profusion of other wild and exotic animals, giraffes such as this one captivated the imagination of those who saw them in parades and public games. Writing around the turn of the third century, the historian Cassius Dio (about A.D. 150–235), among others, called this marvelous creature a Camelopardus because, in his opinion, the giraffe combined the physical traits of both the camel and the leopard.

Gift of Mrs. Robert B. Mayer

1993.345

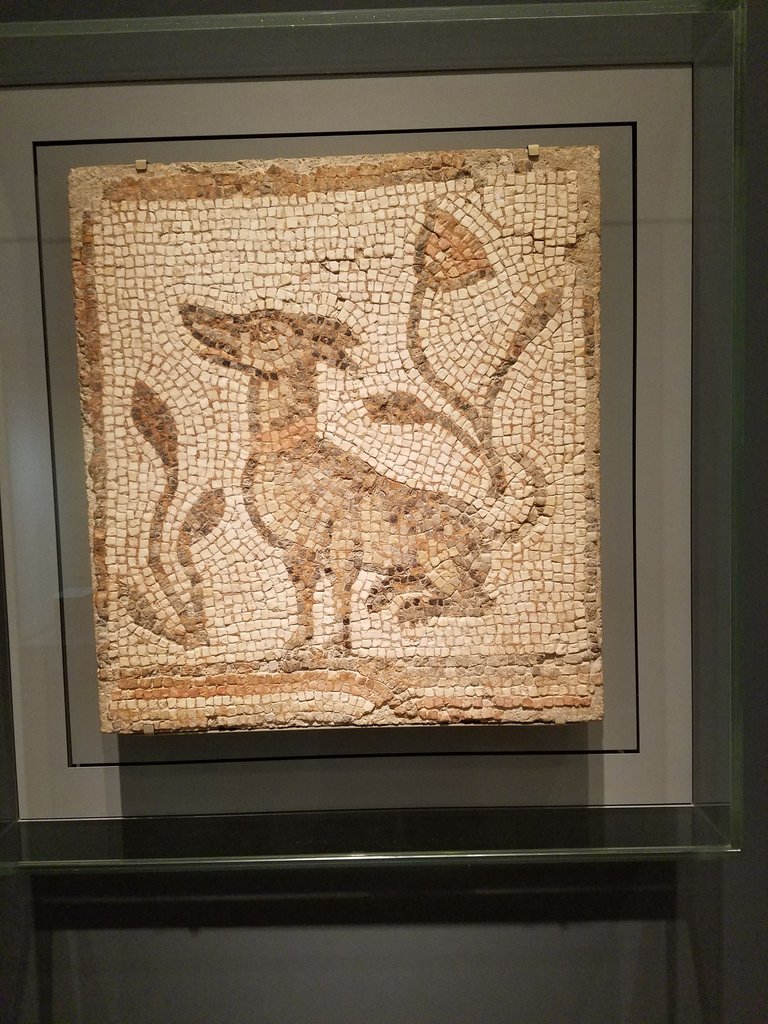

Byzantine mosaic of a dog:

CONTINUED IN ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO (PART 2)