As the fiery ball of the sun began to rise over the eastern bank of the Ganges on our left-hand side, the lighted candles on banana leaves, offered in prayer to the gods, started to float past our boat. The oars lapped gently in the water as the high stepped bank, on our right hand side, gradually became a hive of industry. Woman’s saris, individually vivid as they were picked out by the sun’s earliest rays, were being readied for washing; men stood almost naked lathering themselves with soap; goats lay watching events unfold; religious rituals commenced; ablutions began; prayers were being said and people immersed themselves and each other in the Holy River, as smoke drifted across from a nearby cremation. The day had begun on the ghats at Varanasi.

A dawn boat ride on the Ganges is the highlight of any trip to Varanasi, also known as Banaras or Benares. Situated in the state of Uttar Pradesh, Varanasi is a sacred centre of Jainism, Sikhism, and Buddhism. However, for over 2,000 years it has been the religious capital of Hinduism more revered and sacred than all the other places of pilgrimage put together. Varanasi is known to devout Hindus as Kashi, the Luminous or the City of Light, one of the oldest living cities in the world.

Half an hour earlier, I had arrived at Dasasvamedha Ghat to find an oarsman for my boat ride. From the throng of potential rowers, I had decided to try Sandeep, whose salesman’s patter: “ I am a strong boy who will get you where you want to go, ” had made me laugh.

Heading upstream, we first passed the Munshi Ghat, where the city’s Muslim population, roughly one-third of the total, comes to bathe even though the river has no religious significance for them. Dhobi wallahs or professional washermen then began to appear, standing in the water up to their knees in a long line, washing clothes and then slamming them repeatedly on large flat stones with such great force, that you hear the sound echoing across the water, almost before seeing the washermen themselves. Large areas of the bank were even now, covered with their laundry, drying already in the warm glow of early morning. There is religious merit in having your clothes washed here and the Brahmins, the highest of the sects in Hindu society, have their own washermen to avoid caste pollution. Just as we approached Harischandra ghat, the most sacred smashan or cremation area, I noticed two white bundles float past us. “ What were those? ” I asked Sandeep. “ They are children sir; we do not burn children. ” I also found out that people, who have died of a high fever, in the past it used to be smallpox, are not cremated but are just thrown into the river, in deference to Sitala the goddess of smallpox.

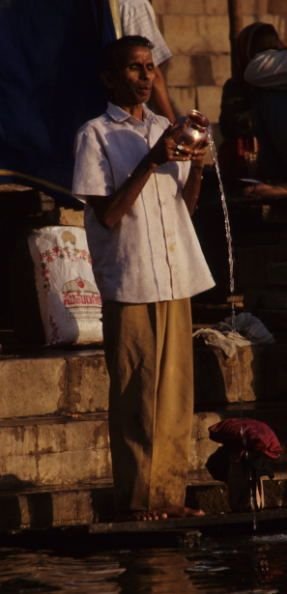

We stopped a moment to watch a group of women washing their saris in the water and then rinsing them with the utmost care. One woman was cleaning her son, scrubbing him roughly, washing his hair and then rinsing it with Ganges water poured out of a kettle. Next door was a man’s ghat, where a fully-clothed man was standing with a beaker in his hand at waist height, letting some water fall from it gently whilst reciting a prayer. Next to him a large bearded man with a potbelly held a bowl over his head and poured the water from it silently and yet quite majestically over himself.

Sandeep turned the boat around and we moved downstream past our starting point to Man Mandir Ghat, where the Maharajah of Jaipur converted a palace into an astronomical observatory in 1710. Cricket matches were noisily being played here on a flat stretch of the bank by the Dom Raja’s house. The Doms are the ‘ Untouchables ’ of Varanasi who perform the parts of the cremation service that all other Hindus would find ritually polluting. People were enjoying themselves swimming around the boat and smiling as I photographed them; others were diving into the water from the stepped bank, where some Western tourists were sitting silently with their eyes closed facing the sun.

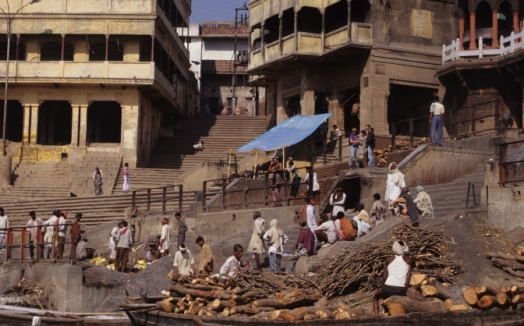

Shouts of “No photos” greeted our arrival at the principal burning ghat of the city, Jalasayin. From my vantage point in the boat, I could see the bodies waiting to be cremated, wrapped in the most colourful sheets. Relatives were fussing around the grieving family members as the funeral pyre was being built a few metres away and children were playing on the huge pile of wood at the back of the ghat. Each log will have been weighed on giant scales to calculate the price of the cremation.

As a mark of respect, you should not take pictures on the burning ghats, even with a long lens, as people have been handed over to the local police for ignoring the warnings. The elderly come to Varanasi to seek refuge or to live out their final days, finding shelter in the temples and being assisted by alms from visiting pilgrims. Hindus believe that anyone who dies in Varanasi attains instant moksha or enlightenment and as a result cremation is big business. Outcasts, known as chandal, carry bodies on a bamboo stretcher swathed in cloth through the alleyways of the old city to the sacred Ganges.

Along the riverbank at the Panchganga ghat young boys were flying multi-coloured kites. Serious competitors try to bring down other flyer’s kites by coating their twine with a mixture of flour paste and crushed light bulbs to make it razor sharp. Unbelievably, my two hours were almost over, so Sandeep rowed me back to the Dasavamedha Ghat and the most photogenic vista of colour I have ever witnessed came to an end. It was so awe inspiring that I got up even earlier the following day, to view the ghats at sunrise once again.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.intltravelnews.com/2008/02/enthralled-by-an-early-morning-boat-ride-on-the-ganges