Welcome steemians to this space of stories about the Venezuelan Andean moors, below is a story about Guaraque, a village in the south of the Venezuelan Andes.

Historical references indicate that the word 'Guaraque' comes from an autochthonous word that means; "people hardened", by the energetic character of the natives who lived in the surrounding mountains and valleys at the time of the arrival of the Spanish conqueror.

The population of Guaraque was founded by Salvador Fernández de Rojas in the year 1653, as a town of encomiendas. With the arrival of the new Iberian settlers in the land of the Guaraques and the entire Andean region, there was a turn in the history of the Venezuelan Andes.

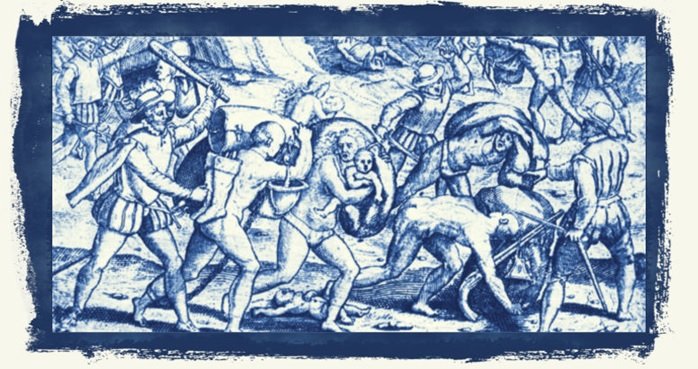

Engraving 15th Century. Parcels.

The encomiendas were established in America according to a custom brought from Spain, it was something like a fief received by a Spanish subject. The distribution of encomiendas to Hispanics, in theory, was to favor the Indians of their internal wars with other tribes, to teach them Spanish and to catechize them in the Catholic faith. With the encomienda, the kingdom of Spain gave to a Spaniard called encomendero, a certain number of Indians who were under their responsibility, in return for that favor, the Indians had to deliver tribute to the encomendero in gold, brilliants, precious metals and labor, but, in this region of the Venezuelan Andes, the conquistadors did not find all the expected riches and were considered poor regions, the Indians paid with servitude, working in the ranches of the encomenderos.

The regime of the encomienda generated a series of abuses, the system derived in many cases in forced labor, the indigenous were forced to perform rough jobs, if they opposed, they were subjected to punishment until death- In practice, the difference between the encomienda and slavery was minimal. Initially it was established, that the encomienda lasted for two generations, soon the encomenderos became accustomed to the land of the natives who were under their protection, and they took over them in time.

The friar Bartolomé de las Casas dedicated his life to writing and exerting pressure, to abolish the system of colonial encomienda that enslaved the natives of the New World. Bartolomé de las Casas intervened in the debate that prompted the enactment by King Carlos I, on November 20, 1542 the New Laws, which prohibited the slavery of the Indians and ordered them to be freed from the encomenderos and placed under direct protection of the Crown, but only two hundred years later, in 1720, the end of the encomienda system in America and the end of the seventeenth century, was replaced throughout the Spanish America by repartimientos.

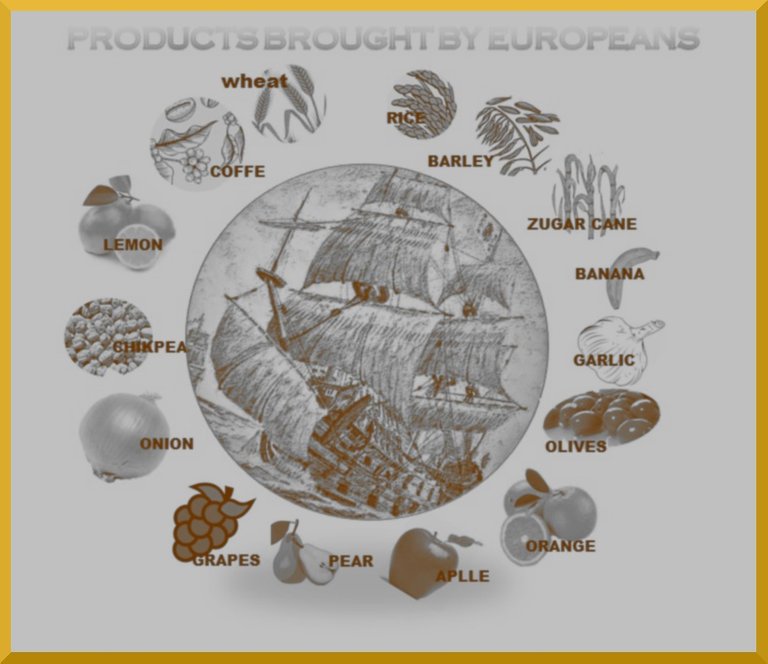

From the sixteenth century, this region of the Andes was reached from the Viceroyalty of New Granada, beginning the founding of the southern peoples; Guaraque, Canaguá, Guimaral, El Rincon, Acarigua, Acequias, Chacantá, El Molino, El Morro, Mesa Quintero, Mucuchachi, Mucutuy. In this process, the colonizer introduced agricultural products brought from Europe, such as wheat, sugar cane, lemons, oranges, pea, cambur, garlic, onion, increasing the exchange of goods with the Viceroyalty of New Granada and the Caribbean.

Also the Castilians in the colonizing process implemented the use of swords, knives, machetes, yuntas of oxen, farming implements: plow, hoe, hoe, scythe, sickle, shovel, rake, to work the land and moved from the Iberian Peninsula animals domestic like; cows, chickens, horses, mules, donkeys, sheep, dogs and cats.

Horseshoe roads were built according to Spanish custom, these roads were made based on the old indigenous trails, were narrow roads through the mountain, made by pick and shovel, they advanced harassed by the screams and whistles of the muleteers the beasts of load, rows of mules carrying bales, through dirt roads and paved, climbing hills, sometimes, the paths were hindered by landslides of earth and stone, forcing travelers to stop and clear them. Through these paths sculpted in living rock, arrieros, baqueanos and travelers made their journey walking through the Andean mountains, accompanied by the cold breeze of the haze of the moors caressing their faces, noticing from the heights, deep chasms, waterfalls, lagoons , streams, cloud falls, all forming spectacular landscapes, which were recorded in the memory of travelers who contemplated them.

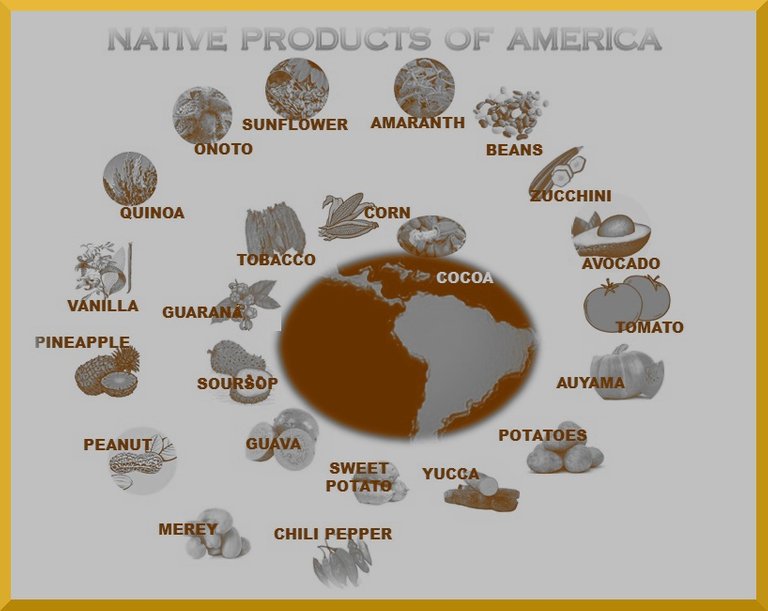

The natives traditionally planted in conucos according to the different climatic floors, in the regions where the southern towns were founded. They used manual tools such as: wooden shovels, axes and stone shovels. They cultivated corn, beans, potatoes, sweet and sour yucca, peas, wheat, chayota, tobacco, priests or avocado, arracacha or celery, sweet potato, chili, cocoa, fruits soursop, peanuts, the pineapple, the merey, the peanut, the pineapple, the milky, and others today almost unknown as the amaranth, the quinoa, the ruba, the michiruy, the quiba, the istú, the cuyre, the navilla, the chuba. Community work predominated among the indigenous peoples, for the gathering of the crops a call called cayapa was organized, a type of community work organization. To cook they had firewood stoves and containers made of baked clay such as: muráis, chorotes, jícaras, chirguas, moyas, and diverse utensils made of totuma or tapara.

Traditionally the natives cultivated the mountains on terraces and platforms, they channeled the waters of the Serrano rivers for irrigation, using systems of ditches through which they drove the water to their fallows and conucos. They used ponds or quimquets to accumulate and use intakes for consumption and irrigation of crops. They also built stone walls with the purpose of protecting the mountain slopes of erosive processes. They had shelter in caves for rituals, to preserve their food and to bury their dead.

Ruins of old coffee house near Guaraque.

In the last part of the 19th century, from the 1870s, due to the climate of the region, its geographical conditions, with heights of more than one thousand meters above sea level, increased the coffee crop in the Andes for its growing international demand. The inhabitants of the region of Guaraque and of the Peoples of the South are dedicated to the cultivation of this plant, which would contribute to many of its inhabitants, prosperity for the next 60 years. The coffee grew very well on the mountainous slopes of the Andes of Merida, which made it an ideal space for this crop, producing abundant harvests.

Guaraque was part of this reality, due to its boundary border with Táchira and the North of Colombia. Due to the coffee boom of those years, Guaraque registered a growth of its population. At that time the llaneros arrived from the southern towns escaped from the civil war, both oligarchs and laborers. Also settled in these lands, Italian, French, and German families of which remain descendants. Likewise, Colombians from Norte de Santander arrived, accustomed to the rude tasks of the land and known for their commercial ability. Once the processed and dried coffee in the haciendas was transported in bales by mule trains, along the roads of the time, to Tovar and Santa Cruz de Mora, it was transported to Lake Maracaibo, where it was transported to Colombia and the Caribbean.

Map of the roads to get to Guaraque from Mérida

At present there are two routes coming from the City of Mérida to reach Guaraque by land. One entering through Tovar, passing through the town of San Francisco, up the hill and crossing the National Park of the Páramos de Batallón and La Negra. Going down we reach the town of Guaraque, located on a branch of the Andes mountain range. Another way is, coming from Santa Cruz de Mora, going up by Estanques, going through El Molino, Capurí, entering by Quintero Mesa until arriving at Guaraque.

With the territorial political law of 1992, it was established that the Guaraque Municipality will have an extension that covers the five hundred and forty-six square kilometers, by that time it had a population of nearly ten thousand inhabitants. The municipality was conformed by three parishes: Guaraque, Río Negro and Mesa de Quintero. This region is located in lands of the Capurí basin. The inhabitants live on agriculture as their main activity which allows them to sustain themselves by cultivating; coffee, celery, banana, sugar cane, potatoes, vegetables, and a livestock sector.

Festivities of Santa Bárbara in Guaraque

The Christian religion is determinant in the encomiendas and in the towns of doctrine. The priests sought to educate the Indians in the principles of the Catholic faith. This task is assumed by religious congregations such as the Augustinians and the Dominicans, who settled in the mountainous area of the Andes and the foothills of southern Mérida towards hot lands of the plains.

Catholic evangelization establishes a new religious imaginary, a syncretic conformation of the Catholic beliefs and the traditions of the indigenous settlers. In time, beliefs are mimicked in a dual cosmogony, which lasts among the inhabitants of the Andean highlands. For the descendants of the indigenous population, the new symbolism and the Catholic priest, somehow replace the piache, although they do not disappear, they blend with different names: healers, midwives, curacas, yerbateros, but, by persecution and prejudice religious taxes, not all are what they claim to be and remain reserved in the Andean mountains.

In these villages the work of the priests is marked during the year, to attend to the parishioners according to the distance and available mobility, but the brotherhoods in towns, hamlets and villages, fulfill their organizing function in the various religious celebrations which throughout of the year corresponds to moments of sowing, harvesting, harvesting and enjoyment among family and neighbors. The Christmas holidays continue with the new year and the child's paradura, so called, because the child stops from his cradle and visits the houses of the neighborhood, is commemorated in all the Andean towns to culminate with the celebration of the feast of the candelaria on February 2, these celebrations are accompanied with processions, prayers, songs, rockets, meals, Andean sweets and the Andean miche.

The Carnival precedes Easter, has symbolic agricultural elements in relation to sexuality by the warmth and warmth of the earth where plants are germinated. For the peasant Easter Week has a symbolism related to agriculture, the representation of the death, burial and resurrection of Christ, has a representation linked to the fertility of the earth, the commemoration ends with Easter, the good news, the life won death corresponds to the arrival of the first rains and the rebirth of life in the crops.

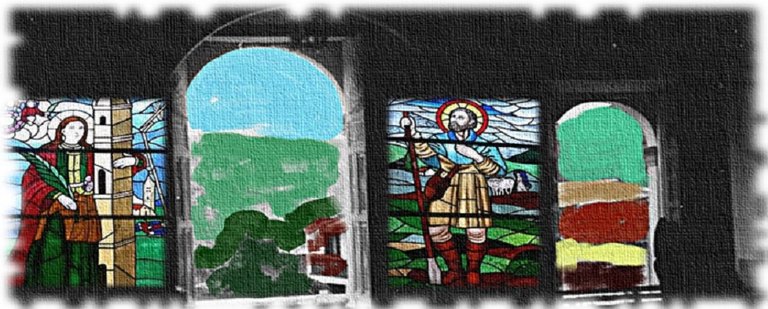

Santa Bárbara and San Isidro Labrador.

A festival of deep roots among the inhabitants of Guaraque and nearby villages. Hundreds of devotees arrive from different parts to honor and venerate her. They are the festivities in honor of the Blessed Virgin Santa Barbara. With these festivities the Andean cosmovision is expressed over water, fire, air and earth. The tradition in honor of Santa Barbara is celebrated in Guaraque with much emotion, music, popular dances, cultural and sports days. Santa Bárbara is a mediator before nature for beneficial rains and is invoked to calm storms, overflowing rivers, thunder, lightning and sparks. The story of Santa Barbara came to Guaraque with the Spanish conqueror and has many stories, which I will tell you in a future post.

San Isidro is a celebration of the peasants that was implanted from the colony. The first rains soak the earth, germinate the seeds and the field becomes green again. The brotherhoods in the different towns promote the rituals to San Isidro is the protective saint. During the celebration the peasants, make a clean oxen yokes, tractors, work tools and vehicles for the transport of crops, this consists of passing bunches of herbs on top, the intention of this symbolic gesture is that agricultural instruments purge yourself of all adversity and receive blessings from the saint in the new cycle that begins. In the festivities of San Isidro the oxen are dressed in color, squares and churches are adorned with arcades of flowers and fruits. The peasants come down from the fields and villages to celebrate, all wear their best clothes. That day there will be commemoration with mortars, music, hullabaloo, food stalls, there will be plenty, chicha, chimo, miche, cakes, chicken sancocho and typical Andean sweets.

There are times when it rains too much, the excess water that causes mudslides, floods of streams and rivers, roads are damaged, the plains are flooded and the peasants go to San Isidro to mediate before the uncontrolled elements and let it rain singing, San Isidro Labrador, remove the water and put the Sun.

Cueva Benito, Google Earth location: 8.1139, -71.7432

Near Guaraque is the Benito cave, located within the Juan Pablo Peñaloza National Park, to which the Páramos de Batallón and La Negra belong. It is considered the largest in the Venezuelan Andes and the second largest in Venezuela, inside presents galleries with rock formations, stalagmites, and different colorations of rocks. The speleologists explored a stretch of 2Km, without finding the end of the cave. Its interior runs a stream that forms a waterfall. So far this cave has not been explored in its entirety, it is possible that telluric movements have closed galleries and not explored their length, the deep galleries make it a labyrinth, and it is recommended not to venture because the inexperienced have a chance to get lost.

The Cueva de Benito at 2,200 m altitude, is framed in a landscape of great tourist interest made up rock formations, mountain savannahs, and fruit growing areas. From its location you can see panoramic views of Guaraque, Negro River, Quebrada Seca and Huesca. It is about 4 kilometers from, you can by double-traction vehicle and then up a trail on foot. The road is only walkable in summer time and access to the interior of the cave becomes difficult during the winter due to the abundant vegetation.

The Cava Benito is a reference on what is respected for the inhabitants of the region. It is commented among the taitas, that in another time, the cave was a place of worship of the indigenous ancestors, it is a place of respect that connects the memories of yesterday and today, and requires an adequate conservation environment. In the cave you can see traces that corroborate that in its interior various rites were performed, confirmed through visualization of the stage that define spaces marked by traces of past cults. Inside the cave there is a place for rituals dedicated to water. They tell stories of farmers who practice this tradition of planting water during Good Friday and December 24.

There is another large cave near the town of Pregónero in the Táchira State, in the Quebrada la Escalera, which is connected to the Cave Benito. The oral tradition tells that the Indians exchanged for salt the salt that the missionaries brought, in these stories it is said that this cave communicates with the Cave Benito near Guaraque. It is said that the Indians used these caves for years as a way to trade for barter with the Guaraques. It is also said that these caves are enchanted and those who try to pass can die.

Uribante-Caparo basin and dam

In the moors, the Black and the Battalion are the springs of the river basin: Mill, Guaraque, Negro River, Capurí, due to the slope of the mountains, the drainage of the waters is torrentoso, along this river basin there are the populations of Guaraque, Rio Negro, Mesa de Quintero, El Molino and Capurí. Water is available throughout the year, coming together in the Uribante-Caparo dam located in Táchira State for the generation of hydroelectricity. Paradoxically the electricity generated from the Uribante-Caparo dam, benefit to the residents of Guaraque and other towns in the south, ten years after its entry into operation. Sometimes the territorial political division is an impediment to the harmonious development of the regions, for years the territorial division between Mérida, Barinas and Táchira, disturbed the development of the southern peoples, limiting the communication routes to the plains of Barinas and Crier. Farmers have to take their products to the Chama basin by mountain roads which are affected in periods of rain.

Until next time where we will be telling more stories of the southern peoples.

- References

- http://www.nuevatribuna.es/articulo/historia/encomienda-explotacion-indios/20161014095646132715.html

- The encomienda: the exploitation of the Indians

- http://erevistas.saber.ula.ve/index.php/revistaagraria/article/download/10014/9942.

- Guaraque in Three Times: Prehispanic, Colonial and Modernization in its Historical-Agrarian Development by Luis Alfonso Rodríguez Carrero. Right Magazine and Agrarian Reform Environment and Society Nº 41, 2015: 47-58 ULA-Venezuela. December 2015

- Infographics and photo montage MMP

This is a wonderful piece. It deserves attention. I will resteem. Not sure that will help, but I hope it does. Also, if I resteem, the article will be in my blog and I can read later, more carefully, when I am less pressed for time.

Thanks for your opinion. It really is impressive the paths of the people who inhabited these lands and those who came to the American continent, are stories of human beings who have no other way to adapt to continue living.

MMP