This is transcribed from my travel journals written while trekking through the Himalaya in the summer of 2014. The photos were taken with a Canon pocket camera.

July 23, 2014

The sun was hot this day, unabated by clouds. Clear blue sky at 3500 meters. The other day we made it through Rohtung-la Pass by jeep. These were the Himalayas of Himachal Pradesh, a place more diverse than I could have imagined. Some mountains formed deep valleys, there were snow-capped ridges visible in all directions, and waterfalls on the cliffs like strands of silver. I saw great walls of swirling metamorphic rock, some more than a kilometer high. Even the shoulders of the mountains were towers of unfathomable size, some flat and populated with villages surrounded by cultivated land, others were pristine shades of green. A few of the mountains were held together with massive fissures of rock resembling the buttresses of medieval cathedrals. It was easy to see symbolism in the landscape — cathedrals, the valley of the gods. The peaks resemble crowns, and above 6000 meters could be a portal into a higher realm.

From the pinnacles spill enormous glaciers that cut deep into the Earth, as if dragons had sharpened their claws upon them. Waterfalls spill through the canyons and merge into a raging river. Until passing the tree line, much of the land is covered in pines and orchards. Above there is a place like a terraformed moonscape — the Rohtung-la Pass, clouds covering the mostly barren rock where some of the only living things are lichens and moss. There are occasional flowering plants in between the cobbles. Glaciers sleep embedded in the swelled earth. I saw the occasional red bird, a few crows, and many wild horses — white horses that were like lesser spirits living in the purgatorial landscape. You can hear the silence even through the roar of the jeep’s two-stroke engine, could almost see it. Beyond that endless fog is the Himalayan range, and I could feel their presence without seeing them.

There I was in the front seat of this jeep with a Russian and a German fellow that I’d only just met, us and our driver from Manali, traversing the winding, unpaved and incredibly thin mountain passes toward Keylong.

Keylong is a small village above a valley so deep that the Earth seems to have folded in on itself. The shoulder across the valley is home to small villages that look like spilled salt compared to the size of the mountain they sit on. There are stupas scattered around the villages, and a gompa (monastery complex) large enough to serve every villager there. Seven legendary peaks tower over the others, and I cannot remember their names but the range itself resembled a sleeping dragon. Farther east are snow-capped mountains where on this day a cloud concealed the upper limits of the Earth. From where I stood it felt as if the Earth and universe really could go on forever.

July 24, 2014

I had spent the night in a dingy bunk room owned by a man running a tea shop just at the edge of the road to Nordaling, but only for one night. I don’t mind staying with the locals, but the holidaying Indians are intolerable. The shop owner tried to hustle me for extra cash as well.

Hopefully future travelers will choose to stay at the hotel Nordaling instead — a pleasant and spacious homestay, 300 rupees a night for solitude, silence and a place to wash up. There was a map of India over my bed, and the bed was regularly cleaned. For that part of the world and most of India that I experienced, these sorts of features are valuable.

Exploring Keylong, I found that it was well equipped to be so far out of the way. There was a bakery, some dabas (something like an independent fast food shop), travel agencies and nice guesthouses. It is a good place for a passing traveler. I noticed buildings in various stages of construction, mostly meant for guesthouses.

We left Keylong by taxi, this time our driver was the owner of Hotel Nordaling. The road up to Keylong is terrible but after a while the gravel transitions to a freshly paved road. For a sum of rupees our driver took us as far as Jankar Sumdo. From there we would attempt to walk as far as

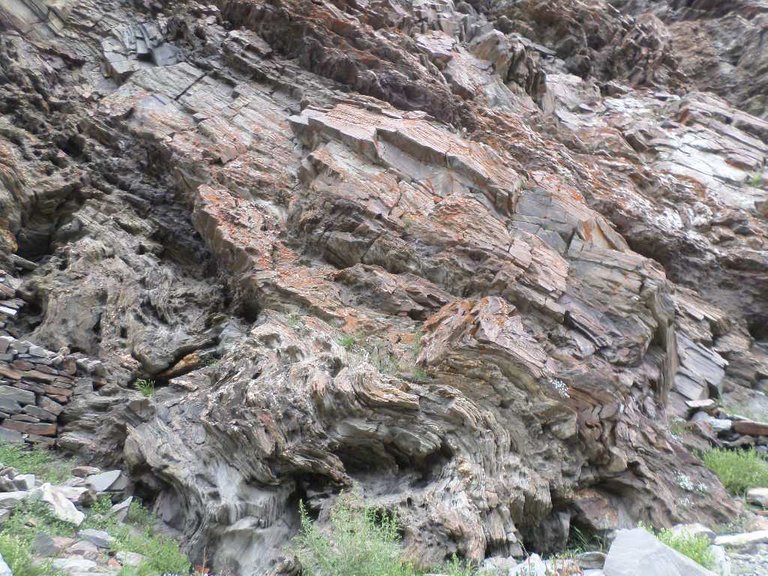

En route we passed through the Lahaul valley, a wooded landscape of steeply rising towers of orange-red stone over green valleys and flats of conifers and flowering plants. The landscape became more immense with each turn revealing a higher view of the world below. Something that began as a giant would progressively blend in with the boulders hundreds of meters below. Now we were surrounded by taller mountains and deeper valleys still. Then above it all in the distance were the snow-capped titans of the Great Himalayan Range.

We trekked uphill from Jankar Sundo for a few kilometers and travelled a ways up the valley until reaching a good place to set up camp. A water source wasn’t ten minutes away, next to a construction site where men were busy carving out the road to Padum. That road wouldn’t be complete for another decade or more — we were entering the outer realm of it all.

We were maybe half an hour from Rumjak, a valley exclusively inhabited by a few shepherds. As we set up camp, there were hundreds of sheep grazing far up the mountain. Behind us was a raging river, and we were already accustomed to the roar of it. It flowed faster than any natural river I’ve seen, fed by the glacial melt further upstream. The German and I used a tarpaulin, stakes and some string to fashion a shepherd’s tent for the night.

The valley where we camped was a place of great power. I sat on the grass and felt the wind roll by, the sun on my face. Evening came, I woke up to find sheep all around me. The shepherds came with their dog, we had supper and when night arrived a cold air filled the valley.

I developed a terrible headache. It was foolish to ascend so fast, probably equally as foolish to drink vodka the other night. I knew that it was altitude sickness, as I’d had it before. I wanted to battle through it instead of descending to Jankar Sundo, and so I stayed there in the valley.

I lost a lot of liquid and nutrients that night, and that made me convulse and feel delirious. It was to this day one of the most miserable days of my life, but I think it was also one that hardened me. It was something that I could fall back on whenever facing resistance in the future.

--

Thank you all for reading, I hope that you found value here.

People often ask me how I manage to fund all of these adventures. I use two vehicles to keep this thing rolling. One is cryptocurrency donations or upvotes on Steemit. Find @sariun and me talking about magic internet money here.

If you're interested in making good money teaching kids English from your computer, even if you're traveling the world, check this out.

Here's to the new economy!

See more @rotiwokeman

Hmm where are my photos...