Who are the Japanese? Where did they come from? What

are the origins of this unique people?

During the eighth century a scribe named Yasumaro

compiled—at the behest of the Empress—the oldest traditions

that had survived. He produced two books: the

Kojiki (“Records of Ancient Matters”) and the Nihongi

(“Chronicles of Japan”). These provide information about

the earliest days of the nation, and about its cosmological

origins.

In the beginning, we are told, the world was a watery

mass—a sea that surged in darkness. Over it hung the

Bridge of Heaven.

One day Izanagi and Izanami—brother-and-sister deities

—strolled onto the Bridge. They peered into the abyss

below. And Izanagi, wondering what was down there,

thrust his spear into the water. As he withdrew it, brine

dripped and congealed into a small island.

Izanagi and Izanami descended to the island. And they

decided to live there and produce a country.

They began by building a hut, with the spear as center

post. The next step was to get married. For a ceremony,

Izanagi suggested they walk in opposite directions around

the spear and meet on the other side. Izanami agreed. But

when they met, she said: “What a lovely young man you

are!”

Izanagi grew wrath. The male, he insisted, must always

be the first to speak. For Izanami to have done so was

improper and unlucky. So they walked around the spear for

a second time. “What a lovely maiden you are,” said Izanagi

as they met.

Now they were wed. And they coupled. And Izanami

gave birth to the islands of Japan…to the mountains and

plains, rivers and forests…to the gods and goddesses of

those places.

And they created a sun goddess—Amaterasu—and

placed her in the sky. For the islands needed a ruler. And

they created a moon god, to keep her company. But Amaterasu

and the moon god quarreled. So they decided to

separate the pair—one presiding over day, the other over

night.

And they created a wind god, to dispel the mist that

shrouded the islands. And the islands emerged in splendor.

And Amaterasu shone upon them, and reigned as their

chief deity.

But a quarrel arose between Amaterasu and the storm

god. And in a pique, she withdrew into a cave—plunging

the islands into darkness. In consternation the gods and

goddesses assembled. They discussed how to entice Amaterasu

out of the cave. Finally, they came up with a plan.

A mirror was placed in the Sacred Tree. And a party was

held—a raucous affair of wine and song. Mounting an overturned

tub, the goddess of mirth performed an indecent

dance; and the others laughed uproariously at the sight.

Amaterasu peeked out of the cave to see what was going on.

“Why are you rejoicing?” she asked.

Someone pointed to the mirror, explaining that a goddess

more radiant than she had been found. Amaterasu stepped

out of the cave for a closer look. And as she gazed upon her

own radiance, they grabbed her and shut up the cave.

So Amaterasu resumed her place in the sky, illuminating

again the islands of Japan.

But the darkness had left disorder in its wake—had

allowed wicked spirits to run rampant. So Amaterasu sent

her grandson, Ninigi, to rule over the islands directly. As

symbols of authority, she gave him three things: her necklace,

a sword, and the mirror that had enticed her out of the

cave.

“Descend,” she commanded him, “and rule. And may

thy dynasty prosper and endure.”

Ninigi stepped from the Bridge of Heaven onto a mountaintop.

And he traveled throughout Japan, establishing his

rule over its gods and goddesses. And he wedded the goddess

of Mt. Fuji. But he offended her father, who laid a

curse upon their offspring:

Thy life shall be as brief as that of a flower.

And so was born man.

And Ninigi’s great-grandson was Jimmu Tennu, the first

Emperor of Japan. Jimmu conquered the islands, established

a form of government, and built the first capital. And

his dynasty would endure.*

This, then, is what the ancient chronicles tell us about

the origins of Japan. They go on to describe the doings of

the early emperors.

And the modern view? What do science and scholarship

have to say about those beginnings?

According to geologists, the Japanese islands rose from

the sea during the Paleozoic era—the result of volcanic

upheavals. And the Japanese people, according to ethnologists,

are the product of a series of migrations. Nomadic

Mongoloids came to the islands via Korea; seafaring Malays

arrived from the south. Eventually they intermingled.†

The Kojiki and Nihongi were written, historians tell us,

- It endures to the present day: the current Emperor is the

125th of the same lineage.

† That intermingling also included the Ainu (or Hairy Ainu, as

they were once known)—a Caucasian people who were the original

inhabitants of the islands. During historical memory the

Ainu retreated to eastern Honshu, then to the wilds of Hokkaido,

where a few thousand remain to this day. Many place names

are of Ainu origin.

with a political purpose. By the eighth century the Yamato

clan had imposed its rule over rival clans. To legitimize this

ascendency, the clan claimed for its ruler a divine origin—

an unbroken descent from the sun goddess. The scribe edited

his material accordingly. And much of that material

—the stories of gods and goddesses and early emperors—

derived from the tribal lore of the Yamato.

Thus, the chronicles are a fanciful mixture of myth and

history, fable and folklore. And the true origins of the

nation must remain obscure.

Or must they? There is a Chinese legend that could cast

some light on the question. It concerns a voyage of discovery

launched from China during the Ch’in dynasty.

Leading this expedition was Hsu Fu, a Taoist sage.

His

aim was to locate the fabled Islands of Immortality—with

their Elixir of Life—and settle them. Hsu Fu embarked

upon the Eastern Sea, we are told, with a fleet of ships;

3000 men and women; livestock, seeds, and tools. They

found the islands, but not the elixir. Deciding to stay anyhow,

they settled in the Mt. Fuji area—a colony that was

the nucleus of the Japanese people.* - Hsu Fu would seem to have been a historical personage. His

tomb is located in the town of Shingu, along with a shrine in his

honor. The locals say he taught their ancestors the art of navigation.

Islands

The Chinese called them Jih-pen—the Place Where the

Sun Rises. To the inhabitants of the islands that became

Nippon, or Nihon. And an early emperor—viewing his

domain from a mountaintop and struck by its elongated

shape—dubbed it Akitsu-shima, or Dragonfly Island.

Peaks of a submerged mountain range, the islands form

a chain that stretches from Siberia to Taiwan. They are separated

from the mainland by the Sea of Japan, with its

strong currents. This barrier led to a physical and cultural

isolation, and a unique perspective. It produced a hermit

nation, for whom the dragonfly—with its eccentric beauty

—is an apt emblem.

The Japanese archipelago comprises thousands of

islands. Most of them are small; and it is the four main

islands—Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu—that

provide the nation with living space. Of these Honshu has

the largest population; while Hokkaido, in the north, is still

sparsely settled.*

Japan is basically mountainous—three-quarters of its

terrain. These mountains are covered with forest and largely

uninhabited. The population is crowded into valleys,

coastal plains, and sprawling cities. Every inch of available

land is cultivated; and a bird’s-eye view reveals interlocking

contours of mountain, river, and field.

Swift and unnavigable, the rivers have played a minor

role in the settlement of the nation. Rather, it is the sea that

has shaped Japan—and fed her. (The Japanese consume a

tenth of the world’s ocean harvest.) The coastline meanders

endlessly (its total length approaching that of the equator);

and no cove or bay or inlet is without its fishing village. http://www.professorsolomon.com - The last refuge of the Ainu, the northern island was originally

called Yezo, or Land of the Barbarians. It was renamed Hokkaido,

or Gateway to the Northern Sea, as a public relations ploy

to attract settlers.

Geologically, the islands are young and unstable, having

been thrust from the sea in relatively recent times. The

legacy of that upheaval is an abundance of hot springs, geysers,

volcanos (240 altogether, 36 of them active), and sulphurous

exhalations from deep within the earth. But the

most common reminder of Japan’s instability are earthquakes.

Daily occurrences, they are caused by movements

of the Pacific Plate beneath the islands.*

Subject to frequent natural disasters—earthquakes, tidal

waves, volcanic eruptions—and short on habitable space,

these islands would seem an unfortunate choice for settlement.

Yet they offer a compensation: ubiquitous scenic

beauty. One is never far from a breathtaking vista—of

mountains or sea or both. The farmer plants below a cloudcapped

peak. The traveler follows a winding mountain

road. The fisherman casts his net into a misty lagoon. And

the poet sighs at a crag with its lonely pine.

How this landscape has affected—has shaped—the

Japanese soul may only be guessed at by an outsider. Lafcadio

Hearn (see page 148) has attributed the artistic sensibility

of the Japanese to the mountains in whose shadow

they dwell:

It is the mists that make the magic of the backgrounds;

yet even without them there is a strange, wild, dark beauty

in Japanese landscapes, a beauty not easily defined in

words. The secret of it must be sought in the extraordinary

lines of the mountains, in the strangely abrupt crumpling

and jagging of the ranges; no two masses closely resembling

each other, every one having a fantasticality of its own.

When the chains reach to any considerable height, softly

swelling lines are rare: the general characteristic is abruptness,

and the charm is the charm of Irregularity.

Doubtless this weird Nature first inspired the Japanese

with their unique sense of the value of irregularity in decoration,—taught

them that single secret of composition

- Quakes were once attributed to the movements of a giant fish.

This creature was believed to be sleeping beneath Japan. From

time to time it would stir, striking the sea floor with its tail and

causing an earthquake. When it merely arched its back, the

result was a tidal wave.

which distinguishes their art from all other art.…that

Nature’s greatest charm is irregularity.

This most aesthetic of peoples does appreciate the charm

—as well as the sacredness—of its mountains. Indeed, its

unique insight may be that the two are mysteriously linked.

Fuji

In ancient times the mountains of Japan were sacred

places. Their shrouded peaks were deemed a gateway to the

Other World; their wild recesses, the dwelling place of gods

and ghosts. They were revered, too, as a divine source of

water. The streams that flowed to the rice paddies below

were a gift from the goddess of the mountain. Few mountains

were without such a goddess, or a pair of shrines in her

honor (a small one near the summit; a more elaborate one

—for prayers and ceremonies—at the base). And adding

to the mystery of mountains were their sole inhabitants:

the yamabushi (“mountain hermits”). These ascetics were

reputed to possess magical powers, and to be in communication

with supernatural beings. They were sought out as

healers.

Today only a few mountains have retained their sacred

status. But one of them—a dormant volcano 60 miles north

of Tokyo—has become the subject of a national cult. It has

inherited the reverence once accorded to one’s local mountain.

I am referring, of course, to Mt. Fuji.

The high regard in which Fuji is held is suggested by the

characters used to represent its name. They signify “nottwo”—that

is, peerless, one-of-a-kind. The name itself

derives from Fuchi: the Ainu goddess of fire who inhabited

the volcano. One can imagine the awe inspired in the Ainu,

and in the Japanese who supplanted them, by a mountain

that spewed fire. And in its day, Fuji was fiery indeed.

Tradition has it that Mt. Fuji rose out of the ground—

amid smoke and fire—during an earthquake in the fifth

year of the Seventh Emperor Korei (286 B.C.). Geologists,

it is true, scoff at this account, insisting on a much earlier

formation. But there were witnesses. A woodsman named

Visu is said to have lived on the plain where the mountain

emerged. As he and his family were going to bed that night,

they heard a rumbling and felt their hut shake. Running

outside, they stared in amazement at the volcano that was http://www.professorsolomon.com - The woodsman Visu was to become the Rip Van Winkle of

Fuji. It seems that witnessing the birth of the mountain left him

exceedingly pious—so much so that he did nothing but pray all

day, neglecting his livelihood and family. When his wife protested,

he grabbed his ax and stalked out of the house, shouting that

he would have nothing more to do with her.

Visu climbed into the wilds of Fuji. There he wandered about,

mumbling prayers and denouncing his wife. Suddenly he came

upon two aristocratic ladies, sitting by a stream and playing go.

He sat down beside them and watched, fascinated. They ignored

him, absorbed in their moves and caught up in what seemed an

endless game. All afternoon he watched, until one of the ladies

made a bad move. “Mistake!” he cried out—whereupon they

changed into foxes and ran off. Visu tried to chase after them,

but found, to his dismay, that his legs had become stiff. Moreover,

his beard had grown to several feet in length; and his ax

handle had dissolved into dust.

When able to walk again, Visu decided to leave the mountain

and return to his hut. But upon arriving at its site, he found both

hut and family gone. An old woman came walking by. He asked

her what had become of the hut and told her his name. “Visu?”

she said. “Impossible! That fellow lived around here 300 years

ago. Wandered off one day and was never seen again.”

Visu related what had happened; and the woman said he

rising out of the earth.*

Perhaps this account was inspired by a major eruption

that changed the shape of the mountain. For Fuji has erupted

frequently—eighteen times—in historical memory.

Each blast enhanced the supernatural awe in which the

mountain was held. On one occasion (in 865), a palace was

seen hovering in the flames. Another time precious gems

were reported to have spewed from the mountain. And a

luminous cloud was occasionally glimpsed above the crater.

It was believed to surround the goddess Sengen. Apparently

she hovered there and kept an eye out for any pilgrims to

the summit. Those deemed insufficiently pure of heart she

hurled back to earth.

The last eruption took place in 1707, adding a new hump

to the mountain and covering distant Edo (present-day

Tokyo) with a layer of ash. Fuji is now considered dormant.

But the geological underpinnings of Japan are unstable; and

one never knows. The fire goddess could return.*

Mt. Fuji (or Fujisan, as it is called) is an impressive sight.

Its bluish cone is capped with snow and mantled with

clouds. The highest mountain in Japan, it can be seen for

hundreds of miles. The Japanese are connoisseurs of this

view, which alters subtly, depending on the direction, distance,

weather, and light. With its unique shape, historical

associations, and mystic aura, Fuji has become the nation’s

symbol.

It has also been a frequent subject for poets and painters.

The eighth-century poet Yamabe no Akahito wrote:

Of this peak with praises shall I ring

As long as I have any breath to sing.

900 years later Basho, gazing toward the mountain on a

- For a cinematic imagining of that return, see Godzilla vs.

Mothra (1964). As the monsters battle it out at the foot of Fuji,

the mountain suddenly erupts. Even Godzilla is taken aback.

deserved such a fate—for having neglected his family. Visu nodded

and looked contrite. “There is a lesson here,” he said. “All

prayer, no work: lifestyle of a jerk.”

He returned to the mountain and died soon thereafter.

It is said that his ghost appears on Fuji whenever the moon is

bright.

rainy day, composed a haiku:

Invisible in winter rain and mist

Still a joy is Fuji—to this Fujiist!

And Hokusai paid tribute to the mountain with a series

of color prints, in his 36 Views of Fuji.

Accepting these accolades with modesty has been Sengen,

the goddess of the mountain. She continues to reside

on Fuji, ready to hurl from its heights any unworthy pilgrim.

And pilgrims have continued to climb the mountain,

and to pray at shrines in the vicinity.

Of the origin of one of those shrines—built beneath a

tree in the village of Kamiide—a tale is told.

●

During the reign of Emperor Go Ichijo, the plague had

come to Kamiide. Among those afflicted was the mother of

a young man named Yosoji. Yosoji tried every sort of cure,

to no avail. Finally he went to see Kamo, a yamabushi who

lived at the foot of Fuji.

Kamo told him of a spring on the lower slope of the

mountain. Of divine origin, its waters were curative. But

getting to this spring was dangerous, said Kamo. The path

was rough and steep; the forest, full of beasts and demons.

One might not return, he warned.

But Yosoji got a jar and set out in search of the spring.

Surrounded by the gloomy depths of the forest, he trudged

up the path. The climb was strenuous. But he pressed on,

determined to obtain water from the spring.

In a glade the path branched off in several directions.

Yosoji halted, unsure of the way. As he deliberated, a maiden

emerged from the forest. Her long hair tumbled over a

white robe. Her eyes were bright and lively. She asked Yosoji

what had brought him to the mountain. When he told

her, she offered to guide him to the spring.

Together they climbed on. How fortunate I am, thought

Yosoji, to have encountered this maiden. And how lovely she is.

The path took a sharp turn. And there was the spring,

gushing from a cleft in a rock.

“Drink,” said the maiden, “to protect yourself from the

plague. And fill your jar, that your mother may be cured.

But hurry. It is not safe to be on the mountain after dark.”

Yosoji fell to his knees and drank and filled the jar. Then

the maiden escorted him back to the glade. Instructing him

to return in three days for more water, she slipped away into

the forest.

Three days later he returned to the glade, to find the

maiden awaiting him. As they climbed to the spring, they

chatted. And he found himself taken with her beauty—her

graceful gait—her melodious voice.

“What is your name?” he asked. “Where do you live?”

“Such things you need not know.”

He filled his jar at the spring. And she told him to keep

coming for water until his mother was fully recovered. Also,

he was to give water to others in the village who were ill.

He did as she said. And it was not long before everyone

had recovered from the plague. Grateful to Kamo for his

advice, the villagers filled a bag with gifts. Yosoji delivered

it to the yamabushi.

And he was about to return home, when it occurred to

him that the maiden—whose identity he was still curious

to learn—needed to be thanked, too. Nor would it be amiss

to offer prayers at the spring. So once again Yosoji climbed

the path.

This time she was not waiting in the glade. But he knew

the way and continued on alone. Through the foliage he

caught glimpses of the summit of Fuji and the clouds that

surrounded it. Arriving at the spring, he bowed in prayer.

A shadow appeared beside him. Yosoji turned and gazed

upon the maiden. They looked into each other’s eyes; and

her beauty thrilled him more than ever.

“Why have you returned?” she said. “Have not all recovered?”

“They have. I am here simply to thank you for your help.

And to ask again your name.”

“You earned my help, through your bravery and devotion.

As to who I am.…”

She smiled and waved a camellia branch, as if beckoning

to the sky. And from the clouds that hung about Fuji came

a mist. It descended on the maiden and enveloped her.

Yosoji began to weep. For he realized that this was Sengen,

the goddess of the mountain. And he realized, too, that

he had returned not merely to express his gratitude. Nor to

satisfy his curiosity. Nor to pray. But to gaze upon the maiden

with whom he had fallen in love.

Sengen rose into the air, the mist swirling about her. And

dropping the camellia branch at his feet—a token of her

love for him—she disappeared into the clouds.

Yosoji picked up the branch and returned with it to

Kamiide. He planted and tended it. And it grew into a great

tree, beneath which the villagers built a shrine.

The tree and shrine exist to this day. The dew from the

leaves of the tree is said to be an effective cure for eye ailments.

4.jpg

Shinto

To the bewilderment of Westerners, a Japanese may

adhere to several religions. Generally, these are Buddhism,

Confucianism, and Shinto. Each has a province in the life

of the individual. Buddhism focuses on death and the soul’s

future. Confucianism is concerned with ethics and social

matters. And Shinto—an ancient faith indigenous to Japan

—oversees daily life.

In examining Shinto, we may become further confounded.

For it does not conform to our expectations for a religion.

It has no hierarchy, theology, or founder—no sacred

scriptures (although theKojiki andNihongi serve as authoritative

sources for many of its traditions) or Supreme Deity.

And while Shinto translates as “the way of the gods,” it

offers scant information about those gods. What it does provide

is a way of connecting with them—an elaborate set of

rituals and folkways with which to access the divine.

That is to say, to commune with the kami.

What arethe kami? They are the native gods—the sacred

spirits—the supernatural powers—of Japan. Taking their

name from a word meaning “above” or “superior,” they are

the forces that matter. They are the arbiters of destiny, and

are worshiped as such. A Shintoist prays and makes offerings

to the kami. He seeks to please and obey them. They

are the ultimate sources of good and ill—spiritual forces

that to ignore or offend would be folly.

Reckoning with them, however, is no simple matter. For

the number of kami is endless—myriad upon myriad of

them—and their form diverse. The most common type are

nature spirits. These inhabit notable features of the landscape.

A cave, mountain, island, giant tree, junction of

rivers, deep forest, secluded pond, rock with a curious shape

—any of these are likely to harbor a kami. Also having a

kami are natural phenomena such as winds and storms. An

unusual animal may have one. In short, anything that

inspires awe or mystery may be possessed of a kami, and

must be dealt with accordingly.

Yet not all kami are associated with nature. A particular

territory (or the clan that occupies it) may have its kami—

its guardian spirit. An occupation, sphere of activity, or special

problem may have one, protecting or aiding those who

call upon it. There is, for instance, a kami for healing; one

for help in exams; one for fertility; one for defense against

insects; one for irrigation. A number of these were once

living persons. For a kami can be some great personage of

the past—a saint, a shogun, a scholar—who was deified

upon his death.*

Finally, there are kami that resemble the gods of Greek

and Roman mythology. The foremost among them is Amaterasu,

the sun goddess, who rules over heaven and earth.

Unlike most kami, this group has distinctly human characteristics.†

The kami, then, are the supernatural forces to which one

turns when in need. And how does one do that? How does

one establish contact with a kami? How does one enter into

its presence and seek its aid?

By visiting a shrine.

There are more than 80,000 shrines in Japan. Each provides

a dwelling place for a particular kami. One goes there

to pray or worship or renew oneself; to celebrate a birth or

marriage; or simply to experience awe and mystery. Standing

in front of a shrine, the poet Saigyo remarked: “I know

not what lies within, but my eyes are filled with tears of

gratitude.”

A typical shrine will be located in a grove of trees. This

may be the scene of the kami’s original manifestation, or

simply a pleasing locale—a quiet, isolated site conducive to

- The ordinary dead also were important in the Shinto scheme

of things. Their function has been taken over, however, by Buddhism.

See “Festival of the Dead.”

† These gods and goddesses reside at their respective shrines,

scattered throughout the country. But once a year they gather for

a conference at the ancient Shrine of Izumo. The main order of

business is to arrange marriages for the coming year. The conference

lasts for most of October. So October is known as the month

without gods: absent from their shrines, they are unavailable for

supplication.

a spiritual experience. A sakaki (the sacred tree) may grow

nearby. A spring may gush from the earth. The natural surroundings

are important, and are considered part of the

shrine.*

Important too is the approach to a shrine. The path leads

through an arch called a torii. (The word means “bird

perch.”) The torii serves as gateway to the sacred precincts.

Passing through it, one begins to feel the presence of the

divine. The mundane world has been left behind.

The sanctuary itself is a simple building—unpretentious

yet elegant. It is old and made of wood (to harmonize with

the surrounding trees). Guarding its entrance may be a pair

of stone lions. Out front are colored streamers (to attract the

kami); a water basin; and a box for offerings. But the key

element is kept in the inner sanctum, where only the priest

may enter. It is an object called the shintai—generally a

mirror, jewel, or sword. In this sacred object resides the kami.

Without it the shrine would be an ordinary place. With it

- In cities shrines are sometimes built on the roofs of office

buildings. Yet it was deemed crucial that they retain a connection

with the spirit of the earth. The solution has been to run a soilfilled

pipe between the shrine and the ground.

the site is sanctified.*

No regular services are held at a shrine. Instead, worshipers

come when they feel the need. They begin by kneeling

at the basin and washing their hands and mouth. This

purification rite (known as misogi) is fundamental to Shinto,

which sees man in terms of pure and impure rather than

good and evil. One cannot connect with a kami unless spiritually

purified—cleansed of polluting influences—rid of

unclean spirits. In ancient times purification involved

immersion in a lake, river, or waterfall. The rite has been

simplified, but remains essential.†

After ablution, one bows and claps twice. The claps

attract the attention of the kami. (A bell may also be rung.)

One then drops a coin in the box, and offers a silent prayer

—communes with the kami. One may pray for health, fertility,

a good harvest, protection from fire or flood. It is also

customary to inscribe a prayer on a wooden tablet. Finally

one stops at a stall on the grounds and makes a purchase:

an amulet, a slip of paper with a fortune on it, or an artifact

for one’s kamidana.**

At least one priest resides at any sizeable shrine. But

unless it is a special occasion or time of day, the worshipers

will have no contact with him. For the Shinto priest con-

- For anyone other than a priest to gaze upon the shintai would

be an impious act. A certain Lord Naomasu once visited the

Shrine of Izumo and demanded to be shown its sacred object.

The priests protested; but Naomasu forced them to open the

inner sanctum. Revealed was a large abalone, its bulk concealing

the shintai. Naomasu came closer—whereupon the abalone

transformed itself into a giant snake and hissed menacingly.

Naomasu fled, and never again trifled with a god.

† According to the Kojiki, ritual purification originated with

the gods. When Izanami died and went to the Underworld, Izanagi

followed her there. He unwisely gazed upon her and became

polluted. To restore himself, he hurried home and engaged in

water purification. The rite was passed down to men.

** The kamidana (“god shelf”) is a small shrine found in traditional

households. It contains talismans (one for Amaterasu,

another for the local kami); memorial tablets for one’s ancestors;

and offerings such as sake, rice, or cakes. Domestic prayers are

recited at the kamidana.

ducts no service, delivers no sermon, offers no sage advice.

He is solely a ritualist—a mediator between kami and worshiper.

His duties include the recital of prayers, the performance

of rites, and the overseeing of offerings. Garbed in

headdress and robe, he blesses infants and performs marriages.

And, of course, he presides over the annual matsuri, or

festival.

Many shrines are the focus of an elaborate festival. Held

in honor of the kami, these festivals go back centuries.

Their origins are diverse. Some began as a plea to the kami

for protection—against plague, enemy, earthquake. Or as

propitiation for an abundant harvest. Or as thanks for a

boon bestowed on the community. Others commemorate

some historical incident—a military victory, say. Others

simply pay homage to the kami.

Such festivals evolved locally. So each acquired its own

theme and imagery. There is a Sacred Post Festival, Whale

Festival, Welcoming the Rice Kami Festival, Laughing Festival,

Open Fan Festival, Spear Festival, Dummy Festival,

Sacred Ball Catching Festival, Lantern Festival, Umbrella

Festival, Ship Festival, Kite Flying Festival, Fire Festival,

Rock Gathering Festival, Naked Festival—and hundreds

more. But for all their individuality, Japan’s festivals share

the same set of rituals. And all have the same aim: to renew

the bond between kami and worshipers.

A festival takes place throughout town. But it begins at

the shrine. The sanctuary has been specially decorated with

flowers, banners, and streamers. Elsewhere on the grounds

the priests have been preparing themselves: bathing repeatedly

and abstaining from certain acts. They gather now at

the sanctuary, along with a select group of laymen, and conduct

a purification ceremony.

Then priests and laymen approach the inner sanctum

and prostrate themselves at the door. Sacred music is

played; an eerie chant is intoned; and the door is opened.

Revealed is the shintai—the mirror, sword, or jewel in

which the kami resides.

An offering of food or sake is brought forward: an invitation

to the kami to attend the festival. The door is closed;

and the group adjourns to a banquet hall. There they hold

a sacred feast, which begins with a ritual sipping of sake.

But the event soon becomes more informal—and the sake

flows. Guests of the kami, they commune with it in a joyful

fashion.

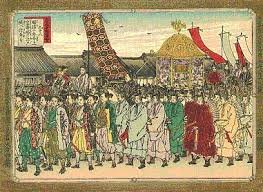

Now comes the high point of the festival: the procession.

Priests and laymen return to the sanctuary, bringing with

them the mikoshi, or sacred palanquin. The mikoshi is a

miniature shrine attached to poles. It is ornate, gilded, and

hung with bells. Atop it is a bronze hoo.*

Again the inner sanctum is opened. And in a solemn ritual,

the kami is transferred to a substitute shintai inside the

mikoshi. Here it will reside for the duration of the festival.

Hoisting the mikoshi onto their shoulders, the laymen—

directed by the priests—begin the procession. The idea is

to transport the kami throughout the town, that it may

bestow its blessings upon all. Exhilarated by the nature of

the occasion (and having drunk large amounts of sake), the

laymen dance and reel and sing as they go.

But the mikoshi bearers are only the vanguard of a larger

procession. For they are soon joined by a collection of floats.

On these wagons are giant figures—dragons, fish, samurai—that

have been crafted from paper; historical tableaux;

displays of flowers; and costumed maidens, dancers, and

musicians. To the beat of drums, the procession winds

through the streets.

Lining the route are local residents and visitors. These

festival-goers have also been enjoying puppet plays, game

booths, fortunetelling birds, sumo bouts, tug-of-war

matches, exhibitions of classical dance. They have been

buying toys, amulets, sake, snacks. Such amusements are

considered an offering to the kami. As the crowd eats,

drinks, and socializes, a rare loosening of restraints is

allowed—a dispensation from the kami. The bond between

kami and worshipers is being renewed; and it is a joyful

occasion.

Also being renewed is a sense of community. For the fes-

- The hoo is the legendary phoenix of the Orient. It is said to

appear in a country only when a wise king rules.

tival serves to bring together the local parishioners. (Even

those who have moved away return to their hometown for

its annual festival.) They have gathered to receive the blessing

of the kami—to pray for health and prosperity—to celebrate

their solidarity as a group.

Among those present are a growing number of persons

who have abandoned Shinto—who view it as an outmoded

set of superstitions. They have come for the carnival; and

they smile tolerantly upon the religious aspects of the festival.

Yet as modern-minded as they are, they find themselves

affected by the aura of mystery that hovers about the mikoshi.

By the transcendental gleam of the sacred palanquin.

By the power of the kami as it passes among them.

Zen

A thousand years after the Indian prince Gautama had

become the Buddha—the Enlightened One—while sitting

under a bo tree, Buddhism (the codification and elaboration

of his teachings) reached China and Japan. There it

flowered into a number of sects. One of these—known in

China as Ch’an (“meditation”) Buddhism, and in Japan as

Zen—was to be a major influence on Japanese civilization.*

What is Zen? The question can be a dangerous one, as

novice monks in Zen monasteries can attest. Putting it to

their Master, many have been answered with a slap, kick,

or bop on the head. The luckier ones were answered nonsensically,

told to go chop wood, or called “Blockhead!”

Those who persevered have spent years trying to comprehend

the nature of Zen—sometimes succeeding, sometimes

not. What they have never succeeded in doing, however,

has been to get a straight answer from their Master.

“What is the fundamental teaching of the Buddha?”

asked one monk. “There’s enough breeze in this fan to keep

me cool,” replied his Master. http://www.professorsolomon.com - The founder of the Zen sect was Bodhidharma, an Indian

monk who had wandered into China. Legend has it that Bodhidharma

was summoned to the palace at Nanking, and brought

before Emperor Wu. A fervid supporter of Buddhism, the

Emperor boasted of his accomplishments in behalf of the faith—

building temples, copying scriptures, securing converts—and

asked what his reward would be, in this world and the next. No

reward whatsoever, said Bodhidharma. Frowning, the Emperor

asked what the basic principle of Buddhism was. Nothingness,

vast nothingness, said the monk. Taken aback by these puzzling

replies, the Emperor asked: “Who are you, anyhow?” “No idea,”

said Bodhidharma.

Departing the palace, Bodhidharma made his way to a cavetemple

in the mountains. There he sat in meditation for nine

years, staring at a wall. As his followers grew in number, Zen

Buddhism was born.

“What is the Buddha?” asked another monk. His Master

replied: “I can play the drum. Boom-boom. Boomboom.”

What is going on here? What sort of religion is this? And

who are these so-called Masters—these antic churls, so

enamored of absurdities and seemingly indifferent to the

progress of their pupils?

The answer is that they are the eloquent spokesmen of a

worthy tradition. But that tradition has charged them with

a difficult task; and in seeking to perform it, they often

resemble slapstick comedians.

That task isthe communication of the ineffable. The teaching

of a truth that cannot be expounded. The imparting of

a Higher Knowledge that is beyond words. For such (in a

few useless words) is the aim of Zen.

Now a quest for enlightenment is not unique to Zen.

All

denominations of Buddhism seek to understand the Universe,

and to enter into a harmonious relationship with it.

To that end they have employed both intellectual and ceremonial

means. In the temples and monasteries of the Buddhist

world, logical discourse has flourished. Elaborate rituals

have evolved. Endless volumes of theology have been

written, circulated, and diligently perused.

But Zen alone has disdained such activity—in favor of

an intuitive approach.

Learn to see with the inner eye, Zen urges seekers of

enlightenment. Forsake reason, logical discourse, and books

(and while you’re at it, toss in dogma, ceremony, and icons).

For a keener faculty than the intellect is available to you.

There is a direct route to the Highest Truth—to the vital

spirit of the Buddha. And that is via intuition. Via the

heart, not the mind.*

- Westerners may find it difficult to conceive of a non-rationalistic

mode of philosophizing. The story is told of the abbot of a

Zen monastery who gave to an American a gift of two dolls. One

doll was a Daruma (the Japanese name for Bodhidharma). Daruma

dolls are weighted at their base, the abbot explained. Pushed

over, they spring back up. But the second doll was weighted in

the head—pushed over, it stayed down.

“It represents Westerners,” said the abbot, “with their top-

What Zen offers is a “hands-on” brand of enlightenment

—a moment of perception—an experience of the Highest

Truth. And it calls that experiencesatori.

This post has been ranked within the top 80 most undervalued posts in the first half of Dec 03. We estimate that this post is undervalued by $10.74 as compared to a scenario in which every voter had an equal say.

See the full rankings and details in The Daily Tribune: Dec 03 - Part I. You can also read about some of our methodology, data analysis and technical details in our initial post.

If you are the author and would prefer not to receive these comments, simply reply "Stop" to this comment.

Informative and long and detailed. thanks.

A very interesting post, however it would be cool to make it shorter and make more then one post about it. I read the first part and then my eyes started to hurt lol. Ill have to finish it later. I also adore mythology and history, and japanese culture. Maybe I will get around to posting about it as well!

reminds me of my super duper long Tuatha De essay

this is an awesomely interesting post..