1 in 5 Highly Engaged Employees Is at Risk of Burnout

Paul Reid/Getty Images

Dorothea loved her new workplace and was highly motivated to perform. Her managers were delighted with her high engagement, professionalism, and dedication. She worked long hours to ensure that her staff was properly managed, that her deadlines were met, and that her team’s work was nothing short of outstanding. In the first two months, she single-handedly organized a large conference – marketing and organizing all the details of the conference and filling it to capacity. It was a remarkable feat.

In the last weeks prior to the event, however, her stress levels attained such high levels that she suffered from severe burnout symptoms, which included feeling physically and emotionally exhausted, depressed, and suffering of sleep problems. She was instructed to take time off work. She never attended the conference and needed a long recovery before she reached her earlier performance and wellbeing levels. Her burnout symptoms had resulted from the long-term stress and the depletion of her resources over time.

Engagement means flourishing, or does it?

Employee engagement is a major concern for HR leaders. Year after year, concerned managers and researchers discuss Gallup’s shocking statistic that seven out of 10 U.S. employees report feeling unengaged. Figuring out how to increase employee engagement has been a burning question for companies and consultants across the board.

The many positive outcomes of engagement include greater productivity and quality of work, increased safety, and employee retention. These outcomes are in fact so well established that some researchers like Arnold Bakker, Professor of Work and Organizational Psychology at the Erasmus University Rotterdam, and colleagues have linked engagement to the experience of “flourishing at work.” Similarly, Amy L. Reschly, Professor of Educational Psychology at the University of Georgia, and colleagues concluded that student engagement at schools was a sign of “flourishing.”

While engagement certainly has its benefits, most of us will have noticed that, when we are highly engaged in working towards a goal we can also experience something less than positive: high levels of stress. Here’s where things get more nuanced and complicated.

A recent study conducted by our center at Yale University, the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, in collaboration with the Faas Foundation, has cast doubts on the idea of engagement as a purely beneficial experience. This survey examined the levels of engagement and burnout in over 1,000 U.S. employees. For some people, engagement is indeed a purely positive experience; 2 out of 5 employees in our survey reported high engagement and low burnout. These employees also reported high levels of positive outcomes (such as feeling positive emotions and acquiring new skills) and low negative outcomes (such as feeling negative emotions or looking for another job). We’ll call these the optimally engaged group.

However, the data also showed that one out of five employees reported both high engagement and high burnout. We’ll call this group the engaged-exhausted group. These engaged-exhausted workers were passionate about their work, but also had intensely mixed feelings about it — reporting high levels of interest, stress, and frustration. While they showed desirable behaviors such as high skill acquisition, these apparent model employees also reported the highest turnover intentions in our sample — even higher than the unengaged group.

That means that companies may be at risk of losing some of their most motivated and hard-working employees not for a lack of engagement, but because of their simultaneous experiences of high stress and burnout symptoms.

How to maintain high engagement without burning out in the process

While most HR efforts have stayed centered around the question of how to promote employee engagement only, we really need to start taking a more nuanced approach and ask how to promote engagement while avoiding burning out employees in the process. Here’s where key differences we found between the optimally engaged and the engaged-exhausted employees can shed some light.

Half of the optimally engaged employees reported having high resources, such as supervisor support, rewards and recognition, and self-efficacy at work, but low demands such as low workload, low cumbersome bureaucracy, and low to moderate demands on concentration and attention. In contrast, such experiences of high resources and low demands were rare (4%) among the engaged-exhausted employees, the majority of whom (64%) reported experiencing high demands and high resources.

This provides managers and supervisors with a hint as where to start supporting employees for optimal engagement. In order to promote engagement, it is crucial to provide employees with the resources they need to do their job well, feel good about their work, and recover from work stressors experienced through work.

Many HR departments, knowing employees are feeling stressed, offer wellness programs on combating stress – usually through healthy eating, exercise, or mindfulness. While we know that chronic stress is not good for employees, company wellness initiatives are not the primary way to respond to that stress. Our data suggests that while wellness initiatives can be helpful, a much bigger lever is the work itself. HR should work with front-line managers to monitor the level of demands they’re placing on people, as well as the balance between demands and resources. The higher the work demands, the higher employees’ need for support, acknowledgement, or opportunities for recovery.

What about stretch goals? Challenge, we’re told, is motivating. While that can be true, we too often forget that high challenges tend to come at high cost, and that challenging achievement situations cause not only anxiety and stress even for the most motivated individuals, but also lead to states of exhaustion. And the research on stretch goals is mixed – for a few people, chasing an ambitious goal does lead to higher performance than chasing a moderate goal. For most people, though, a stretch goal leads us to become demotivated, take foolish risks, or quit.

Managers and HR leaders can help employees by dialing down the demands they’re placing on people — ensuring that employee goals are realistic and rebalancing the workloads of employees who, by virtue of being particularly skilled or productive, have been saddled with too much. They can also try to increase the resources available to employees; this includes not only material resources such as time and money, but intangible resources such as empathy and friendship in the workplace, and letting employees disengage from work when they’re not working. By avoiding emailing people after hours, setting a norm that evenings and weekends are work-free, and encouraging a regular lunch break in the middle of the day, leaders can make sure they’re sending a consistent message that balance matters.

The data is clear: engagement is key, it’s what we should strive for as leaders and employees. But what we want is smart engagement — the kind that leads to enthusiasm, motivation and productivity, without the burnout. Increased demands on employees need to be balanced with increased resources — particularly before important deadlines and during other times of stress.

IKEA’s Success Can’t Be Attributed to One Charismatic Leader

During my conversations with CEOs, it always comes to a point where they say: “I want to leave a legacy.” Any CEO would be satisfied with the business legacy left by Ingvar Kamprad, the IKEA founder who died last weekend. The store he founded, with its iconic blue and yellow logo and functional, minimalist furniture, is the largest furniture retailer in the world. Latest figures show it has 190,000 employees, 411 stores in 49 countries, and a revenue of 36 billion euros. Famous for its Allen wrench-assembled flat-pack furniture, Swedish meatballs, and the maze-like shopping routes through its showrooms, it hit upon a winning formula. It provided a differentiated offering that disrupted the industry at the time: affordable, build-it-yourself home furnishings sold in massive stores built on cheap, out-of-town real estate. But how did it hit on this winning strategy?

There is no doubt that Kamprad’s personal tenacity, business savvy, and leadership skills account for IKEA’s success. Obituaries across the world give credit to this part of the man (even as they acknowledge that as a teenager, he joined a pro-Nazi group, something he very much came to regret). However, there is another side of the IKEA story that gains less attention. These elements go beyond the charisma and complexity of the founder. When we focus on the puzzle of the man, we overlook important, hidden elements of the company: the paradox of its history, its processes and routines, and its shared, embedded culture of innovation. Sometimes, strategic leadership is about coming up with a great plan and then executing it seamlessly. But often, it’s about reacting intelligently – to an unanticipated challenge, or to a serendipitous comment. In successful firms like IKEA, focusing heavily on the legacy of a founder can obscure these truths, and result in a story that looks a little too tidy with the benefit of hindsight.

IKEA’s success did not result from the kind of planful strategy development that is still taught in some business schools. Quite the contrary. It has been mixture of emergence, haphazardness, and invention through necessity. For example, when the first IKEA catalogue came out in 1951, many retailers had similar, mail-order business models. To crush the upstart, IKEA’s competitors started a price war, almost forcing the fledging IKEA into bankruptcy. As a last-ditch response, Kamprad opened a small show room in the small town of Almhut, in Sweden in 1953. The hope was customers would see, touch, and compare the furniture and the company would be able to claw its way back. “I have never been so scared in my whole life”, he recalled in his memoir. On the day of the opening, about 1,000 people queued outside the shop. Literally overnight, a new business model emerged that sold through a showroom rather than by mail. It became a hallmark of the IKEA way.

Similarly, one day the team was packing away the furniture and a casual remark about how much space a pair of table legs took up led to another revolutionary idea: what would happen if we were to flat-pack our products? The rest is history, but it was a unique offering at the time.

Another part of the company’s unexpected history came in the 1960s, with the opening of a new store of 31,000 square feet that was launched to considerable fanfare. 18,000 people waited eagerly for the store to open. But the popularity was so great that it turned into a disaster: there were too few check-outs, check-out queues got longer, and people got frustrated and started to leave (some taking goods without paying for them). It was this experience that ignited the IKEA self-service model — as shoppers leave the showroom, they pick up their flat-packed goods from the warehouse, put the boxes on trolleys, and bring them to the checkout themselves.

Despite the serendipitous emergence of these key elements of IKEA’s business model, Kamprad did institute strong discipline when it came to financial matters, and this combination of improvisation and rigor is a key part of the company’s success. For example, the complex and opaque company structure of trusts and not-for-profit entities has been a source of criticism, with accusations of tax evasion and the company’s financial dealing remaining, until recently, a mystery. However, this complex set of company arrangements would protect IKEA from corporate raiders and undue external influence, and provide long-term protection and continuity.

The company also has a unique manufacturing strategy and business model. While IKEA’s products are designed in Sweden, they are largely manufactured in developing countries to keep costs down. For most of its products, the final assembly is performed by the consumer which saves space and simplifies the manufacturing process as well as reducing the costs. Over its history, IKEA has rigorously avoided deviating too far from this model.

Kamprad also deserves credit for keeping the company focused on a common purpose: “To create a better everyday life for the many people.” He developed a team of trusted ambassadors to maintain and develop the company’s special culture set out in the IKEA Bible: The Testament of a Furniture Dealer, published in 1976. It goes on, “We shall offer a wider range of well-designed, functional home furnishing products at prices so low that as many people as possible will be able to afford them.” The company values were enacted in its thriftiness, attention to detail, quality, and cost consciousness.

But perhaps least appreciated is the strength of IKEA’s organizational culture that has sustained the world-leading organization over the last 70 years. It has been often said that “culture eats strategy for breakfast”, and IKEA’s management team has focused on building an organizational culture that has inspired tens of thousands of women and men worldwide, irrespective of diverse national cultures: an egalitarian culture where all employees are called colleagues; where everyone is encouraged to think every day how they can improve the company and perform continuous innovation in customer service and products.

Leaders, of course, are necessary. But the success of any endeavor is not down to them alone — it requires a vibrant, empowering culture that can outlast them. Otherwise, companies would fail once they are gone. In the case of IKEA, there has been a range of complex, unpredictable, and contradictory factors that have led to its success. Some were planned, but many were unplanned. Findings about the clear link between CEOs and organizational outcomes are unclear or mixed (Cannella, Park & Lee, 2008; Hambrick, Humphrey & Gupta, 2015; Pitcher & Smith, 2001). Much can be explained by environmental factors, the role of the team around them, or the structure and organizational culture.

Although the idealization of business leaders can often be misleading, it remains very popular. But we’ll learn the wrong lessons if we simply follow the crowd. And this is something that IKEA rarely seems to do.

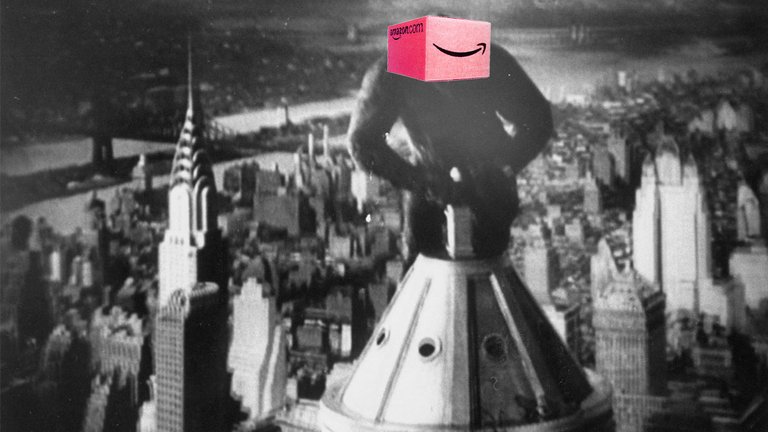

Can Anyone Stop Amazon from Winning the Industrial Internet?

Alfred Eisenstaedt/Hayon Thapaliya/Getty Images

Just the announcement that Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffett, and Jaime Dimon will be entering the health care space has sent shock waves for industry incumbents such as CVS, Cigna, and UnitedHealth. It also puts a fundamental question back on the agendas of CEOs in other industries: Will software eat the world, as Marc Andreessen famously quipped? Is this a warning shot that signals that other legacy industrial companies, such as Ford, Deere, and Rolls Royce are also at increased risk of being disrupted?

To start to answer that question, let’s tally up the score. There are three types of products today. Digital natives (Amazon, Google, Facebook, Microsoft, IBM) have gained competitive advantage in the first two, and the jury is still out on the third:

- Type 1: These are “pure” information goods, where digital natives rule. An example would be Google in search, or Facebook in social networking. Their business models benefit from internet connectivity and they enjoy tremendous network effects.

- Type 2: These are once-analog products that have now been converted into digital products, such as photography, books, and music. Here too, digital natives dominate. These products are typically sold as a service via digital distribution platforms (Audible.com for books, Spotify for music, Netflix for movies).

- Type 3: Then there are products where input-output efficiency and reliability of the physical components are still critical but digital is becoming an integral part of the product itself (in effect, computers are being put inside products). This is the world of the Internet of Things (IOT) and the Industrial Internet.

Manufacturing-heavy companies such as Caterpillar, Ford, and Rolls Royce compete in this world. An aircraft engine is unlikely to become a purely digital product any time soon! Such products have three components: physical components, “smart” components (sensors, controls, microprocessors, software, and enhanced user interface), and connectivity (one machine connected to another machine; one machine connected to many machines; and many machines connected to each other in a system).

Digital natives have already disrupted industries such as media, publishing, travel, music, and photography. But who is likely to assume leadership in creating and capturing economic value in Type 3 products: Digital natives or industry incumbents? Ford or Tesla? Rolls Royce or IBM? Caterpillar or Microsoft? Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan Chase combine or UnitedHealth?

The Challenges for Digital Natives

Value will no doubt be created in the era of smart, connected machines. We don’t expect Amazon or Microsoft or IBM to design, make, and market agricultural tractors, aircraft engines, or MR scanners. The question really is: Can digital natives develop software-enabled solutions that siphon off significant value from industrial hardware? The answer is “yes.” But it won’t be easy. It will require tremendous amounts of investments in building new capabilities for hardware companies like HP, Cisco, Dell, Samsung, and Lenovo; established software companies like Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Microsoft; and start-ups. In particular, there are three barriers they must overcome:

1. The physics of the hardware. Companies like Rolls Royce design and manufacture jet engines. These are very complicated machines. There is hard science behind these machines. That’s much different than digital natives like Airbnb where marketing is more important than technical expertise.

Industry incumbents have expertise in the material sciences, for instance. Further, scientific knowledge keeps improving over time. They have made heavy R&D investments—both basic and applied—to remain at the cutting-edge of the physics of the hardware. Much of this scientific knowledge is protected by patents.

Mastery of hard science is a pre-requisite to develop software-based solutions on the hardware. These companies’ superior product/domain knowledge provides them the comparative advantage to model the asset’s performance and write high-end/high value-added software applications. A “pure” digital company can write commodity software applications. But it must acquire enough capabilities on the physics to write sophisticated apps that improve assets’ performance.

2. Customer intimacy. Industrial giants have well-established brands, built strong customer relationships, and signed long-term service contracts. They’ve won the customer’s trust, which is why customers are willing to share data. Digital natives can work with industrial customers, but they have to first earn their trust; they must build capabilities to understand customer operations; they must match the industrials’ cumulative learning from customer interactions; they must learn to ask for the right data; and they have to hire experts in several verticals that can turn data into insights.

3. Difficulty in sharing risks. Industrial incumbents have product knowledge, customer relationships, and field engineers on customer sites. Companies like Rolls Royce can, therefore, offer outcome deals where they guarantee customer outcomes (examples: zero downtime, higher speed, more fuel efficiency, zero operator error, greater reliability) and share risks and rewards with customers. It would be very hard for Amazon or Google to guarantee customer outcomes and take risks with businesses whose operations they know little about.

The Challenges for Industrial Giants

Can the industrial giants lead in the Industrial Internet? The answer is “yes.” But it won’t be easy for them, either. They too have three significant barriers to overcome:

1. Software talent: The IT talent in industrial companies can execute projects oriented towards process efficiency and cost reduction. That talent is ill-suited to develop new, breakthrough software products that offer superior customer outcomes. For that end, they must be able to attract world-class innovators and software engineers. Is, say, Rolls Royce, in the same consideration set as Facebook and Google for young tech employees? Not, really. If so, how can the industrial giants compete to attract the best talent?

2. Digital culture: Industrial businesses and digital businesses operate with completely different principles. The characteristics of hardware businesses include long product development cycle, Six Sigma efficiency, and long sales cycle. Software businesses have different characteristics: short product development cycle, flexibility, and short sales cycle. The industrials must build a digital culture based on concepts like lean, agile, simplicity, responsiveness, and speed. That’s a tall order for an established enterprise.

3. The Incumbent’s Dilemma: Digital has the potential to disrupt industrial businesses. There are three ways digital strategy can cannibalize “core” industrial business. First, data and insights can help improve the productivity of machines; digital, therefore, has the potential to cannibalize future hardware sales. Second, data and insights increase the reliability of machines; digital therefore has the potential to cannibalize future service revenues. Third, software subscription and license might enable customers to do self-service. Current customers could terminate/renegotiate service contracts, and potential customers may not enter into service contracts at all. In short, it is very difficult for a company to disrupt itself.

The future of the Industrial Internet will involve partnerships across a variety of players including tech companies and industrial companies. The key issue: Who will assume the leadership position to extract maximum economic value in such an ecosystem? Will industrial companies take the lead? Or will the digital natives take the lead? Both have a chance.

If I were a betting man, I would place my bets on tech giants over industry incumbents. One factor that will favor digital companies in the industrial internet is technological/scientific breakthroughs that level the playing field for newcomers. For example, breakthroughs in battery technology made the electric cars possible. Electric cars are much simpler to design than cars with internal combustion engines, allowing Tesla and BYD to enter the market despite Ford’s decades of expertise. Since electrification and driverless cars go together, other tech companies such as Google, Baidu, Apple, and Lyft will also be able to enter the automotive market. Similar technological changes in jet engines and agricultural tractors can allow tech giants gain foothold in these industries as well.

More importantly, Amazon or Google have the resources to acquire the capabilities to master the physics and acquire customer relationships and compete with the industrial giants in the Industrial Internet. They have enough resources and some to buy them, if needed.

Among the tech giants, Amazon is a likely winner in the Industrial Internet. It has successfully fused physical with digital. Amazon understands the economic laws of analog products and is not afraid of massive up-front investments and slower growth. Its acquisition of Whole Foods and experiments with Amazon Go grocery stores are an example. Amazon is the one company everyone’s scared of, even industrial giants.

Source: http://hbr.org/

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://kopitiambot.com/2018/02/03/ikeas-success-cant-be-attributed-to-one-charismatic-leader/