Thursday, 28 September 2017

Welcome to Dispatches, a weekly summary of my writing, listening and reading habits. I'm Andrew McMillen, a freelance journalist and author based in Brisbane, Australia.Words:

I had a story published in The Weekend Australian Review on Saturday. Excerpt below.Sight Unseen (2,500 words / 12 minutes)To read the full story, visit The Australian. Above photo credit: David Geraghty.

For theatregoers with impaired vision, audio description services help to make sense of what's happening on stage.

You are sitting in the front row of a theatre when a calm, male voice begins to speak into your ear, welcoming you and setting out key details about the play you are here to see. "The Merlyn theatre is a flexible, black-box theatre space," says the voice. "For Elephant Man, the audience sits in a rectangular seating bank opposite to the stage. The stage is raised about 40cm off the ground, and takes up the full width of the Merlyn, about 10m wide."

You are listening intently to the voice because you cannot see what it is describing. You are blind, but you love going to the theatre, and you want to better understand the performance beyond the dialogue that all attendees can hear from the stage. This is why you are at the Malthouse Theatre in Melbourne's inner city on a rainy Friday night, listening as the shape and layout of the stage begins to take shape in your mind's eye.

"A black proscenium arch frames the playing area, about 5m tall, creating a wide rectangular space," continues the voice. "A curtain of black gauze covers the entire width of the stage at its front edge, separating us from the playing area. We can see through the sheer material, but it softens the edges of everything behind it."

You are hearing the voice because your earphones are connected to a wireless radio receiver that sits inside the palm of your hand. Later, this wonderful technology will allow you to follow the action you can't follow with your eyes.

While the boisterous audience take their seats behind you in the minutes before a performance of The Real and Imagined History of the Elephant Man begins, you are listening to pre-show notes that are being broadcast into your ears from the green room on the building's third floor. There, a bespectacled 26-year-old named Will McRostie sits before a computer, a live video feed of the stage, and some audio equipment that allows him to speak into the ears of theatregoers who have registered for audio description services this evening.

"The play makes extensive use of smoke and haze effects," says McRostie's voice. "Nozzles emitting smoke are hidden in the walls of the set, sometimes leaking heavy mist that tracks along the ground, and sometimes blasting plumes of light smoke that billows to fill the space. Two powerful fans set into the floor of the space are sometimes activated to catch this smoke and propel it toward the ceiling. On occasion, the smoke is so heavy it becomes difficult to see the performers."

Difficulty in seeing the performers is the entire purpose of audio description, a niche and little-known service that is sometimes – but not often – available for people with low vision who attend theatres and cinemas. Because of its exclusivity and the resources required to produce the service, it is usually available only in Australia's capital cities, and only for the biggest productions on the annual theatre and cinema calendars.

To date, audio description has largely been provided in an ad hoc manner by volunteers and, as a result, the quality of the service experienced by blind patrons can vary wildly. McRostie is at the forefront of a movement to professionalise it, however, which is why he founded an arts start-up named Description Victoria in March this year.

How I found this story: I first learned of audio description services a couple of years ago, via this excellent episode of The Allusionist podcast, where a woman spoke about the difficulties of describing dance films such as Step Up to blind people: how do you put a wordless form of communication into words? That story stayed with me, and I was reminded of it in a conversation a couple of months ago, prompting me to dig deeper into the subject. I found that audio description services for Australians with low vision are rather thin on the ground, especially when it comes to live theatre. I got in touch with Will McRostie, who started a company named Description Victoria earlier this year, and spent time with Will and his collaborators in Melbourne on a couple of occasions. I attended the performance that features in the story above, and sat blindfolded beside Ross de Vent as we watched the stage show while listening to Will's audio description. It was a fascinating experience, and I hope this story introduced a few more people to something they mightn't have heard of before.

Sounds:

K'gari: The Real Story of a True Fake by Fiona Foley on SBS (~10 minutes). This is a beautifully illustrated interactive documentary, which tells the story of the 'capture' of British woman Eliza Fraser by Aboriginal people on Fraser Island (K'gari) in 1836. Eliza was a passenger on her husband Captain James Fraser's ship, the Stirling Castle, which struck reef hundreds of kilometers north of Fraser Island. She claims to have been captured by Aboriginal people, when in reality she was taken in and cared for by the Butchulla people when shipwrecked.

Josh Homme interviewed by Zane Lowe (29 minutes). As mentioned last week, I love Queens of the Stone Age, and I loved this interview with singer/guitarist Josh Homme about songs from the band's newest album, Villains.Unleash the natural forces of K'gari to destroy one of Australia's first fake news stories and return Fraser Island to its rightful name.

Benjamin Law on Conversations with Richard Fidler (50 minutes). An excellent conversation with Quarterly Essay author Benjamin Law about Safe Schools, a helpful educational program for teachers that became politicised.

Hillary Clinton on Longform (54 minutes). I enjoyed this insight into Hillary Clinton's writing process for her new book What Happened, which is about... well, you can guess.In 2010, schools in Victoria began an anti-bullying program for teachers, to help them create a more inclusive environment for LGBTIQ students and their families. Three years later the Safe Schools Program expanded nationwide, with bipartisan political support. But by 2016, the Program was becoming increasingly controversial, and a year later the majority of Australian schools had bowed out. At the centre of the argument, both sides insisted, was the safety of kids in schools. But what happens when kids are caught in a collision between ill-equipped teachers and a media scandal? Writer Benjamin Law has investigated for the latest Quarterly Essay.

Hillary Clinton is the former Democratic nominee for president. Her new book is What Happened. "I hugged a lot of people after [my concession speech] was over. A lot of people cried ... and then it was done. So Bill and I went out and got in the back of the van that we drive around in, and I just felt like all of the adrenaline was drained. I mean there was nothing left. It was like somebody had pulled the plug on a bathtub and everything just drained out. I just slumped over. Sat there. ... And then we got home, and it was just us as it has been for so many years–in our little house, with our dogs. It was a really painful, exhausting time."

Reads:

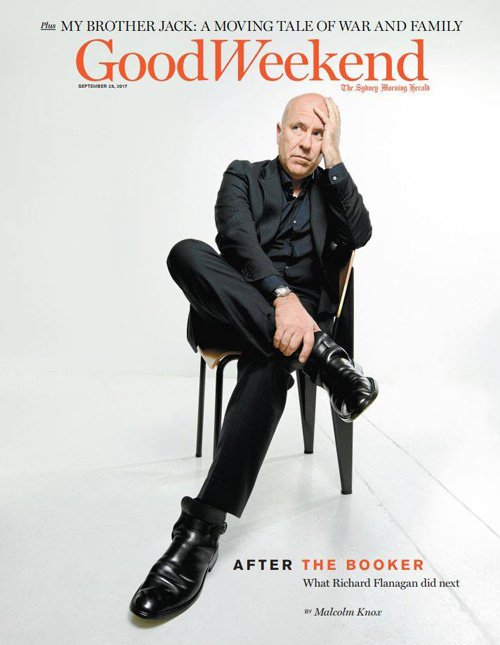

After The Booker by Malcolm Knox in Good Weekend (4,800 words / 24 minutes). An excellent profile of author Richard Flanagan, whose new novel is based on an experience he had decades ago as a ghostwriter for a con man. This makes the second great Australian author profile that Good Weekend has run on the cover in recent weeks, after Jane Cadzow's story on Jane Harper. I love it! More please! I also enjoyed Leigh Sales interviewing Flanagan on 7.30 this week.

How A Hit Happens Now by Craig Marks in New York Magazine (3,800 words / 19 minutes). I enjoyed this insight into how hip-hop has taken over Spotify, which is nearly twice as popular as the next most listened-to genre, rock. I also learned that the most influential hip-hop playlist is called RapCavier, which has 7.8 million followers. Give it a go.The summit of Mount Wellington is not yet in sight. Snow needling into my face, legs burning and chest bursting, boots slipping on ice, it strikes me that Richard Flanagan has brought me here to do me in. He has motive, having just completed a novel that explodes the falsities of "memoir" and "biography" and glories in the deeper truths that come from making things up. Giving interviews on the subject of such an invention is, if not a direct contradiction, something of a problem. He has opportunity – this is the place he comes, according to his wife Majda, to sort out his problems. And he has form. When a previous weekend magazine writer came to Tasmania to profile Flanagan, the novelist hatched a Merry Pranksterish plot to bring the journalist up Mount Wellington, where Flanagan's mates would appear with bottles of hard liquor and disable him. As it happened, the journalist never made it to the mountain: a night on the town, followed by slivovitz for breakfast and a kayaking trip to Flanagan's shack on Bruny Island, finished him off early. "Why slivovitz for breakfast?" asked one of Flanagan's co-conspirators. "He's a mainlander," Flanagan replied. Today, he has scooted over the ice like one of George R.R. Martin's White Walkers (in conversation, Flanagan is as likely to reference Game of Thrones as Goethe's Faust). From high above, he calls: "You need a pulley?" When I reach the snowy knoll where he has stopped, he is boiling coffee. Hobart and the Derwent are laid out spectacularly below. This is one of his special places, where he has come since he was a 14-year-old overnighting in snow caves. "Probably pretty stupid," he says, and then, as I remain doubled over, deep breathing: "So how's your heart these days?" Coffee, not slivovitz: deference to men in their 50s, one a survivor of two open-heart surgeries.

The 'Madman' Is Back In The Building by Zack McDermott in The New York Times (2,000 words / 10 minutes). A gripping insight into managing mental illness at work, and returning to the workforce after an involuntary stay in a locked psychiatric ward. This is an extract from McDermott's book, which I'm now totally sold on. I'm very glad I saw this one at the top of the page when I was browsing nytimes.com during the week.In this, the year hip-hop won the music business, one of its defining hits was released more or less by mistake. Back in February, Lil Uzi Vert, a charismatic, septum-pierced 23-year-old rapper out of Philadelphia who'd become internet famous with a frenetic outpouring of digital singles, EPs, and mixtapes, was on his first tour of Europe, opening a string of shows for the Weeknd. Uzi, who counts late nihilist punk GG Allin and '90s shock-rocker Marilyn Manson as heroes, dove into the crowd during a gig in Geneva. Backstage after the set, he realized he'd lost his phone during the plunge. "He lost two phones, actually," says Leighton "Lake" Morrison, one of the principals, along with veteran producers Don Cannon and DJ Drama, of Uzi's Atlanta-based label, Generation Now. "And he'd broke the screen on a third." Prior to Europe, Uzi and his team had been in L.A. and Hawaii, working on tracks for his first official album, to be released on Generation Now through Atlantic Records. The songs they'd finished were on one of the lost phones. "Yeah, I was upset," says Morrison. "We'd just spent a month and half recording in Hawaii, and I had to justify all this money Atlantic had given us that we'd just blown." Uzi had lost a phone in 2016 that contained some new collaborations with fellow mumble-rap fashion plate Young Thug, and those were soon leaked on the internet. "We didn't want to go through that again." In this new digital era of music consumption, brought about by streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music, many hip-hop artists have rejected the traditional blueprint for releasing new music, which mimicked Hollywood's rollout of a blockbuster film: a lavish, many-months-in-the-making marketing campaign, led by one or two radio-friendly singles designed to create maximum exposure for a record company's big moneymaker, a proper studio album. Streaming is built on a song-based economy, though, and young MCs like Uzi are too savvy and restless to play by the old rules: They spray-hose new tracks when the mood strikes, and fans binge the content like couch-bound Netflix addicts inhaling new episodes of Black Mirror.

Under One Roof by Trent Dalton in The Weekend Australian Magazine (2,700 words / 13 minutes). An original and beautifully written story about an extraordinary family. The star of the show is Becky Sharrock, who is one of the few people in the world to have a condition called Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory, which allows her to recall most of her life in precise detail. I love the way Trent Dalton ends this story.What do you wear the first day back to work after a 90-day leave of absence because of a psychotic break? This is the question I found myself asking a little more than a year after I joined the Legal Aid Society of New York. The last time my colleagues had seen me, I'd been wearing a handlebar mustache better suited to a Hell's Angel than a 26-year-old public defender. I'd also taken to wearing a Mohawk – tried a case like that even. We won, thank God. At the happy hour following that trial, I stripped down to my underwear and did a titillating strip tease for a bunch of law students who were there as a part of a recruiting event for a white shoe law firm. It didn't go over well but I didn't care. I thought I nailed it. For my first day back to work I dressed in a sober navy sweater and a pair of dark slacks. Normal haircut, neatly trimmed beard. I got there early to avoid the morning rush and the inevitable stares and whispers. I had been "away with some issues" – that was the official company line, but offices are gossip hotbeds, and I wondered how much of the real story had filtered through. Did they know that I'd marched through the city for 12 hours – manic, psychotic and convinced I was being videotaped by secret TV producers, the star of my own reality show? That the police had found me later that evening shirtless, barefoot and crying on a subway platform? That I'd been involuntarily committed to Bellevue, the notorious psych ward to which we at Legal Aid routinely sent our most mentally ill clients?

Finding Jack by Greg Callaghan in Good Weekend (4,600 words / 23 minutes). One hundred years ago, amid the carnage of a major World War I battle, a distraught Australian soldier buried his older brother. With great care, Greg Callaghan tells the moving story of how the brother's body was eventually found, identified, and laid to rest with full military honours.All visiting neurotypicals are welcome to use the escape hatch. They can check out anytime they like when the noise and the chatter and the two-hour "I just want to die, Mum" meltdowns get too much. They can climb the rope ladder Janet Barnes has fixed to her living room wall and, with the extraordinary powers of their neuro-typical imaginations, they can open the trapdoor above the ladder marked "Escape Hatch" and discreetly exit the chaos of the blended family's Brady-Bunch-with-a-special-needs-twist existence. Because anything is possible in the Barnes-Sharrock household in working-class Logan, southeast Queensland. It is possible in this house to find success and pain and support and love along the winding continuum of the autism spectrum. It is possible to find an independent adulthood. Brendan Barnes, 18, an apprentice motorcycle spray-painter with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), taps your shoulder politely like he always does when he's about to say something profound. "There's everything in this house," he says. "You've just got to know where to look."

Discovering Manhood in Soapy Bubbles by Nate Martins in The New York Times (1,600 words / 8 minutes). As a long-time dishwasher myself, I feel like this story was written just for me.All this for one lousy strip of shiny tin. It's the first light of dawn in West Flanders, Belgium, and Private John "Jack" Hunter is crouched behind a charred tree trunk, clutching his rifle, his grey eyes peering out into the morning mist. Somewhere out there, in this corridor of death between opposing trenches they call no man's land, his enemies lie in wait behind reinforced concrete bunkers, nests of machine guns at the ready. Some of the trenches out here are so terrifyingly close you can occasionally hear the enemy talking, catch the clack clack of them loading up shells or smell their cooking. But on this autumn morning, all is deafeningly quiet. Only minutes earlier, Jack had received the most dreaded command of all: to go "over the top", to leave the earth-rammed safety of the trench to retrieve a pesky piece of tin reflecting the morning light back into the eyes of the troops further down the field, making it impossible for them to target the enemy. Any second now, this handsome 28-year-old soldier from the small, rural town of Nanango in Queensland, alone in this desolate patch of no man's land, expects bullets to be whizzing past his head. Back in the trench, his younger brother Jim, 25, is standing ankle-deep in an earth-coloured brook, in anxious wait for Jack, as other soldiers shuffle past. Weeks of torrential rain have turned the blue clay soils of West Flanders, already churned up by two-and-a-half years of constant shelling and bombardment, into a vast sea of stinking, viscous mud. The sludge is everywhere – it sticks to your uniform, gets lodged under your fingernails, clogs your rifle – and if you're unlucky enough to slip into a deep mud-filled crater and can't swim (like the Hunter brothers), it's goodnight Gunga Din.

"A Bloody-Minded Bunch Of Bastards" by Andrew Stafford on Notes From Pig City (5,200 words / 26 minutes). This essay was written for the liner notes in Midnight Oil's Overflow Tank box set, which was released earlier this year. Andrew Stafford describes it as "pretty much the best assignment ever", and his enthusiasm shows in every word. It's a brilliantly written piece that covers the band's whole career and looks toward Midnight Oil's forthcoming Australian tour, which I'm very much looking forward to.It wasn't until I started doing dishes that I realized men in my family don't do dishes. At parties, I rarely saw Martins men helping out in the kitchen. Instead, our grandmothers, aunts and female cousins (all Portuguese and Argentine immigrants) would cook and serve the meal, and afterward the men would stack their plates near the sink like a Jenga tower before returning to the table, where they would finish their wine and pick their teeth as the women cleaned up. I decided I would be a different kind of man. When I moved in with my girlfriend, Natalie, I became a man who did dishes. This was in 2015, after we moved to San Francisco from San Diego and started living together after seven years of dating. At 25, we wanted to be closer to family. Natalie already had a good job in the tech industry. I was bartending. In our new life, she cooked and I cleaned up. She fed vegetables into the Spiralizer, creating noodles from zucchini and beets, and made dishes like parsnip-kale gratin, which tasted wildly nutty and was surprisingly filling. I wasn't working full time and washed many, many dishes, a task made even more involved by appliances like the Spiralizer, which had to be disassembled and all of its parts cleaned individually. Before we had a sink, we had a deal: I would have the final say on where we lived if Natalie got to decorate.

The place: 8 Ormiston Avenue, Gordon, a leafy suburb on Sydney's Upper North Shore. The year: sometime in 1972. A teenaged Robert George Hirst hauls his drum kit into the attic of the Cape Cod-style home owned by the parents of James Moginie. Pretty soon, all hell starts breaking loose. There's a thudding bass riff, played by Andrew "Bear" James. A couple of mighty clangs from Jim, and soon he's noodling away over the top of Hirst's kick drum. Hirst, all the while is hooting and hollering: "SCHWAMPY MOOSE! SCHWAMPY MOOSE!!!" It's followed by an even greater cacophony, which sounds like Hirst kicking his drums back down the stairs again, just for the fun of it. Bands have, perhaps, had less auspicious beginnings. So begins the story of Schwampy Moose, soon to be known as Farm, and – later – as Midnight Oil. This box of recordings represents both a purging and a history, but history is rarely linear and never neat. Tentative steps and great leaps forward can be followed and are sometimes accompanied by self-doubt; by glances sideways; by the occasional strategic retreat. It is a collection both of defining and celebrated moments, and of things that fell between the cracks. But always there is purpose, and there is integrity. Those qualities took Midnight Oil to places few artists dared to go. To the Indigenous communities of Australia's central and western deserts. To Midtown, Manhattan for a guerrilla-style protest against an oil company. To a heaving Ellis Park Stadium in Johannesburg, South Africa, in that country's first post-Apartheid, multi-racial concert, following the election of President Nelson Mandela. In purpose and integrity also lies resistance and refusal.

Thanks for reading. If you have feedback on Dispatches, I'd love to hear from you: just reply to this email. Please feel free to share this far and wide with fellow journalism, music, podcast and book lovers.

Andrew

--

E: [email protected]

W: http://andrewmcmillen.com/

T: @Andrew_McMillen

If you're reading this as a non-subscriber and you'd like to receive Dispatches in your inbox each week, sign up here. To view the archive of past Dispatches dating back to March 2014, head here.

Disclaimer: I am just a bot trying to be helpful.