From binge-watching Netflix to adjusting your Facebook page privacy settings, it’s all data and its mostly good.

Data is information, and for millennia, humans have recorded information about everything we’ve encountered and envisioned. Data collection has permeated every facet of our existence, and serves as the default mechanism by which we seek to understand our world.

From notating sun and moon cycles for better crop yields, to transcribing religious texts to pass along our spiritual relationships, to even today when we share vacation photos and videos, arguably, we've always been, and will remain, in the information age.

Demand

The demand for data can be summarized as such, all things being equal, the demand for any collection of data will increase, as the time, energy and cost to access it decreases. Hence, searching Wikipedia for information is far easier than searching a library (time and energy), or buying and maintaining an encyclopedia set (cost).

Demand for data is increasing, and is met by two supply-side mechanics, access and content.

Access

Most of us can remember when the predominant means of Internet access was the dial-up modem. For those who are too young, or weren’t born yet, here’s a brief overview. 20 years ago, home computers used telephone lines to call the Internet and get access to it. Sometimes, there were so many people calling the Internet, the Internet wouldn’t pick up.

When it did answer your phone call, it did so in an excruciatingly slow manner, usually at a fraction of the advertised 56 kilobytes per second. What did this turtle-esque speed cost us, you ask?

Well, first you had to have your telephone company install a second telephone line, in your home, so you wouldn’t interrupt phone conversations that were taking place. This could cost around $30 per month.

Next you had to sign up for and Internet access account, as millions did with AOL, for $20 per month. Initially, AOL would allow you 20 hours of access, but ultimately time-based usage was replaced with unlimited, as skyrocketing demand made it viable.

Content

20 years ago, you paid $50 per month, to wait up to 10 minutes to download a single song from Napster, a free (and illegal) music-sharing app. Users would queue up albums worth of songs and leave them to download via dial-up overnight. In this case, free music, or content, was in such demand, music sales would never be the same.

Needless to say, the demand for digital music remains. And as the .mp3 supplanted the compact disk, streaming music has replaced the .mp3, albeit on a far shorter timescale.

Today, you have access to nearly all musical works, from any genre around the world and from wherever you have Internet access. For roughly the same $50 per month price point as 20-year-old dial-up, broadband, both home and mobile, deliver always-on, instant access to an ever-expanding catalog of content the world has to offer.

Supply

Without supply, demand is simply desire, a wish for something, and it is the supply-side of the equation that brings fulfillment for both consumers and businesses. In its purest form, supply is the delivery of what you demand, at a price point you are willing to pay.

Supply is entrenched in efficiency. Figuring out how to make it both easy for you receive and cost-effective for businesses to deliver, what you want is the crux of competition. This holds especially true for data.

Access

As Internet access technologies have evolved, we’ve seen access become easier and more prevalent; content more diverse and complex, and the speed at which content is delivered, exponentially increased. All of this has happened while what you generally pay for access has stay around the same $50 price point.

To be clear, the supply-side of access is not in the business of delivering slow and sparse Internet access at ever decreasing prices, but rather the opposite. In the physical world, faster delivery and ubiquitous access for various things is what brought us from the Pony Express, to Federal Express; at the demise of the relatively slow and cheap U.S. Postal Service.

So why has Internet speed and access increased, but our $50 price point remained relatively unchanged? It turns out, most people simply wont pay more than $50 for internet, whether at home or on mobile.

This is the market price. It also turns out that, for big telecommunications companies like AT&T, Comcast and Verizon, its more cost- effective to increase efficiency in speed and access, than to convince you to pay significantly more.

How It Works

As you demand more content, you use more access. Your carrier watches this very closely and when your usage hits a predetermined level, more capacity is added to the network, and that cost is divided across all other users to determine what we all pay.

At the same time, carriers are vigorously researching better, more efficient technologies that allow for more users and faster speeds delivered, while keeping that $50 price per user. In fact, today, there is so much efficient capacity, many wireless carriers resell access to smaller, regional access providers in the prepaid market, to generate revenue from unused capacity.

For carriers, some money from prepaid is better than no money from no use, and they work feverishly to lower their cost per megabyte delivered, so you can have a retail choice of providers that suit your budget.

Content

For the majority of human existence, we've sought information, or content, that is meaningful to us, mostly in our daily lives. The demand for meaningful content has given rise to methods in which businesses use to measure what is meaningful to us, hence marketing and advertising.

Marketers match our desires with what business has to offer and then use advertising to move us to purchase. Historically, this meant researching our needs and desires and finding products and services to match- an approach that has served us well.

However, the cost associated with marketing research and promotion, adds to the overall cost of the goods purchases.

In the Internet age, with relatively cheap and ubiquitous access, the sheer number of potential buyers of goods has added significant costs to effectively research, market and transact business.

The cost to find new customers and supply goods and services to them, on a global scale, is out of the reach of all but a few large enterprises.

User-Generated Content

Capitalizing on our demand for more and diverse content, particularly that of which is media-related, content created by individual users has exploded throughout the world. User-generated blogs/vlogs, wikis, discussion forums, posts, chats, tweets, podcasts, digital images and videos, dwarf the catalog or professionally produced content, such as television, newspaper and magazine, and continues to grow at unprecedented rates.

While user-generated content replaces the cost to determine what users want and that contents professional creation, insatiable demand for it also buoys the access price point to remain at around $50 per month. Add to that, nearly all user-generated content is inundated with revenue-generating advertising.

Currently, advertising revenues remain with the content provider, or in the case of YouTube, shared with the content creators. Ad revenue generated from user-generated content is not shared with the access provider, hence the issues around net neutrality.

While we won't dive in to Net Neutrality in this post, it is interesting to note, that as supply-side access costs continue to decrease and access speeds increase, ultimately, provider profits resulting from these efficiencies will have diminishing returns. At that point, either access costs will increase significantly to bring demand in-line, or alternative access technologies will compete to capture market share.

One Solution: Drones and Ads

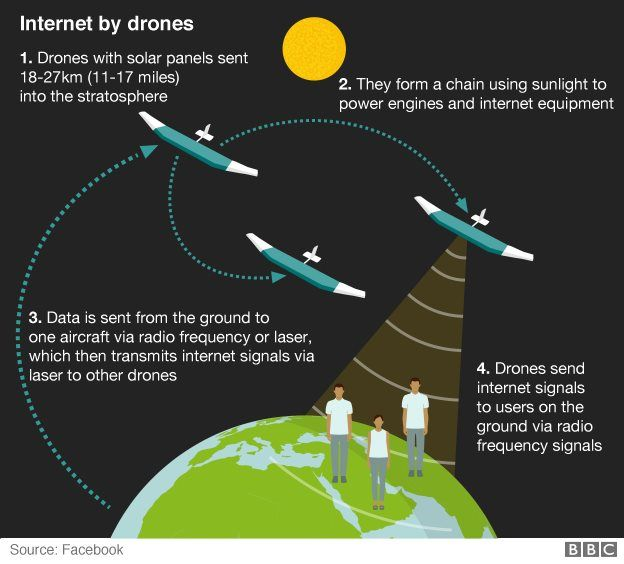

Both Facebook and Google are developing such alternative access technology, in the form of autonomous flying drones. These drones, presumably will beam Internet access to users homes and mobile devices.

This technology represents a significant departure from the supply-side access model we currently use, in that not only is the majority of land-based telecommunications replaced by high-flying drones, providing said access moves to new players.

It is important to remember that both Facebook and Google currently generate revenue from advertising, not from subscriber fees, save Google Fiber.

In our experience, as users of Facebook and Google, we are not accustomed to pay to use their respective services, and in our minds, both are free.

While managing a fleet of drones may be less expensive than a nationwide wireline and wireless telecommunications network, the revenue to operate such a network must come from somewhere.

That somewhere is our data, specifically, the commoditization of both our online and real-world identity, behavior and needs. By cataloging everything we say, read, watch and type, and everywhere we do it, marketers can build extensive psychological, economic and social profiles about us, and sell our data in an international market.

In this model, it makes sense for Facebook and Google to enter the access market and compete with telecommunications companies. By replacing the middle-man, we retain fast and cheap access to content, while Facebook and Google gain unrestricted access to our data.

Privacy

Our data is of critical importance to Facebook and Google, as previously stated, the social media business model uses it to generate revenue. Though a secondary market for telecommunications providers ad revenue is such a lucrative market, that Verizon bought Yahoo for nearly $5 billion to gain first hand access to it.

The content we access on the web, paired with our thoughts and feelings about that content is important to marketers and advertisers in how they determine which goods and services to sell us. With much of the content we consume being created by other users like us, researchers are able to query our data for opportunities en mass, rather than ask us questions about why we buy.

Unbeknownst to many, the privacy policies we blindly agree to are not in place to restrict the use of our data, but ironically, make us aware of how it is to be used, particularly without compensation to us. Simply put, today, we pay to be marketed to, while we consume the content we’ve created.

Protecting Data

The supply and demand for data access and creation has continued to evolve, and we find ourselves with a growing need to protect it. Specifically, we seek greater personal control over who has access to our data. Facebook, Google, mobile apps and the like has near unrestricted access to our data, and we hold them accountable for its security from thieves.

Much like personal property, our data is ours and while we may have nothing to hide and a lot to share, we seek the first and final say in with whom we share it.

The next chapter in data privacy is yet to be written. We have moved from the dial-up days of downloading free music to the new world of fast and ubiquitous access, premium and user-created content with new and disruptive business models emerging every day. However, one thing is clear: data is still paramount and its commoditization is only the first step in a much larger world without wires.

Kind thanks and don't forget- upvote, reply and follow!