I've recently found myself in a very fortunate, relatively small group - aspiring screenwriters finally making a living at their craft. It's been a great couple of years as projects of mine maneuver their way through the Hollywood system toward (we hope) eventually getting green lit and making it to the screen. One of these projects, a World War II thriller, has recently scored some A-list attachments, but even that is a far cry from being a done deal - the Tinsel Town wheels turn slowly indeed. As I've been reflecting on my recent (modest) success, I was thinking back to my first foray into writing for film and find the journey interesting enough to share.

I wrote my first screenplay when I was 15 years old. I was in my third year of medical school at the time. Okay, that’s a lie, I was only a freshman. Yeah, that's not entirely true either, fine. I was actually a pretty typical high school sophomore – I had no game with the ladies, pimples and I was not nearly as smart as I thought (surprising how little has changed since then). After spending a few months writing what I was sure would be the next great action summer tentpole, I was ready to get it to the studios so I could get my big check.

Interestingly, this was the end of the golden era for unknown writers when studios had an open door policy. With surprising ease, I was able to get someone on the phone at Columbia Pictures and pitch my script. Now, I have no idea if they could tell I was a kid, but the fact of the matter is that to this day I still sound like a 15-year-old on the phone. But either way, I was invited to send it in.

A month later, I got back a very detailed rejection letter with coverage. There was a 3 page outline of my story and another 3 pages of thoughts, notes, suggestions and opinions. The feedback was not kind. In fact, it was pretty harsh. What I remember most is that I wasn’t devastated. No one likes rejection and even though the assessment was pretty brutal, I focused on the positives. Actually, I’m not sure I should be using a plural there. There was one positive that I can recall about how fast paced it was. That’s what I embraced. I pretty much ignored the other three pages of mostly negativity. “Not bad for a first attempt” was my mindset as I tackled my second project.

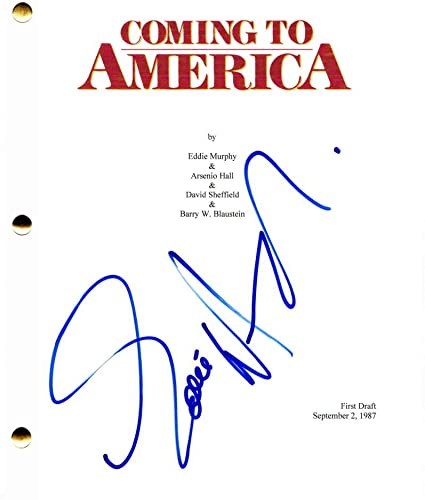

Sadly, this proved to be the only case for many years that I was able to get my writing to the studios. You see, at this same time, a storm was brewing called Buchwald vs. Paramount. The movie Coming to America had recently been released and was a big hit. Humorist Art Buchwald sued Paramount claiming the underlying concept was his - which the studio had optioned several years earlier.

I don’t claim to be an expert on this lawsuit, but Buchwald ultimately prevailed and settled for $900,000 rather than deal with a Paramount appeal. His original treatment is available online and for anyone who knows the film, his outline is a pretty far cry from the movie he claimed resulted from it. But, perhaps I’m on the studio’s side because by the time I had my next screenplay finished, all those doors in Hollywood were closed. In shockingly short order, the new normal was “nothing unsolicited.” This was the era when the gatekeepers truly found their place and power as the new middlemen to help ensure (or at least minimize) that this kind of lawsuit didn’t happen again. The easiest protection against claims or plagiarism is to be able to state emphatically that the project was never read by anyone at any time.

Of course, there have been plenty of lawsuits since then and it seems every big hit has at least a few writers come forward claiming theft of intellectual property. Most of these are thrown out, and rightly so, if you take the time to research them. From my experience, just about every writer I know claims that one of his/her stories has been pilfered or co-opted in some way. The fact that there is no logical paper trail or even plausible connection in almost all of these cases and the “originality” of the ideas are simply not that remarkable makes these claims even less convincing. I probably could have sued Christopher Nolan and Warner Brothers over Batman Begins claiming they stole elements of one my earliest scripts called 'Dodger' – a Bruce Wayne-type superhero with unique access to prototypical weapons and vehicles. The fact of the matter is – there were definitely some similarities, but no one in Hollywood ever saw my script. Perhaps if I had had an agent at the time and that screenplay had done the rounds, maybe I would have been convinced I had been robbed. I’m glad it played out the way it did because I’ve come to realize that pretty much every great idea is only unique to certain degrees. I'm sure countless writers have imagined arming their hero/superhero with futuristic government weapons and vehicles.

There were certainly stories about alternate realities and computer simulations before 'The Matrix'. Spike Jonze wasn’t the first person to think up the idea of a human falling in love with artificial intelligence ('She'). There are obviously many scripts written about and/or set on the fateful voyage of the 'Titanic' that were crafted before the James Cameron film. A good friend of mine believes the premise for the Keanu Reeves’ film 'Chain Reaction' was liberated from a script he had written – though, for me, the idea of rogue government agents trying to steal a new, unlimited energy source didn’t seem so unique to doubt that more than one person might have considered this same concept.

So, now, thanks to Art Buchwald, it's infinitely harder to get your script read. Yes, I do blame him which is why his image holds a place of prominence on my dart board (alongside Zach Braff). Granted, there were some similarities between his story and 'Coming To America', but not enough to justify a $900,000 payday for him. I'm thinking $300 and a couple McDonald’s gift cards would have been fair compensation. The reality is, we are a litigious society and if it hadn't been this case, it probably would have been something similar that would have brought us to the same place. So that's the world we writers live in now. For better or worse, if you try to send a script to the big guys, they’ll send it back, unread. I lament the days when anyone, anywhere could send in their screenplay and have it read by Paramount or Fox or Disney. But as is always the case with time – the rules have changed. Our only play is to change with them.

If your focus in this business is writing, you'll need an agent and/or manger. This can prove to be a monumental task in and of itself since you don't want just any agent, you want the kind of agent that studios and producers pick up the phone for. And there aren't that many of them. But stick with it. As a Oscar-Winning writer once said, "Ninety percent of success is just showing up!" Keep at it, grasshoppers.