A PUBLIC DOMAIN BOOK HAS NO RESTICTIONS FOR YOUR USE

The Race of the Swift

A HALVED moon was shedding a faint glow over the rugged knob country. The twisted, broken, distorted ground, with its spasmodic growth of blackberry, sassafras, and juniper bushes, seemed the center of desolation. But something was living, moving, in the midst of this loneliness. Creeping along a ragged fence line at the base of a knob went a stealthy figure. Sharp-muzzled, keen-eyed, lean of body and wiry of limb, the object moved forward at a swift trot. The night was young. Scarcely had the salmon tints which the sun had left in the west disappeared. Through the pure, lambent air the rolling tones of the farmer could be heard as he called his pigs home. Above the high hills gleamed the timid tapers of the early stars. A low breeze was chanting a gentle vesper among the pines and oaks upon the knob-side. A blundering rabbit butted blindly through the weeds on the creek bank; a bullfrog, fat and inert, bellowed forth his thunderous note; a muskrat splashed softly from a half-sunken log and spread his flat paddles to propel him to his hidden home. A whip-poor-will’s heart-broken tones came from a point further down the hollow. Nature was saying that the day was gone.

The she-fox trotting by the worm-eaten fence stopped abruptly. The fence was curving around the knob, and this did not coincide with her purpose. She stopped with one fore foot upheld, and ears pricked attentively. The sounds she heard were familiar, legitimate; a part of her nightly life. The she-fox was painfully attenuated. Her tawny body was barred with bulging ribs; there was a gaunt, starved look upon her bony face. The two rows of teats along her belly were clean and bare—even moist, for ten minutes ago a half dozen tiny tongues had striven vainly to draw nourishment from them. But she had none to give. For two days and nights she had tasted food but once, and during that time her hungry brood had insistently drawn her very life from her hour after hour. She had given it freely and without grudge, licking caressingly first one baby form and then another; had even borne unflinchingly the sharp nips from little teeth when the milk would not flow. The night before she had ranged for miles, though so weak that only the deathless strength of her mother-love sustained her in her quest. Not far from her home was a place where human-people lived. But they were wary, and placed their hens and chickens under lock and key at the going down of every sun. Thither had she gone first, because it was the closest, but not a feather could she find. At the corner of the hen-house she stopped and sniffed eagerly. Beyond the white-washed planks were scores of fat fowls, and the she-fox knew it, but they were safe from her long, white teeth. She listened. The sound of rustling feathers and drowsy clucks smote her ears, and the saliva of famine dripped from the loose skin of her lower jaw. Emboldened by desperation, she walked around the building. At the bottom of the door a hole had been cut, so that the fowls could enter when the door was shut. But this was secured by a plank, which in turn was held in place by a heavy stone. She could not move it, because she was weak from fasting. Thrusting her sharp, black nose into a crack about an inch wide between the planks, she drank in the ravishing odor of many a choice pullet. Suddenly realizing that this course was worse than futile, she turned, vaulted the fence enclosing the cow-lot, swerved around a prostrate, ponderous figure sleepily chewing its cud, and vanished in the direction of the stable. Here, likewise, her investigation was fruitless, so she gave up and turned her head towards another farm-house, five miles away.

The journey, which ordinarily would not have caused the least fatigue, came near to overcoming the dauntless forager. Near her destination she tottered to a brook and sank in the cool water, lapping it at intervals. This brought back some of her strength, and she essayed to complete her task. Through the orchard she trailed; then suddenly her delicate nostrils conveyed to her subtle brain some welcome intelligence. Stopping about twenty feet from the yard fence, she reconnoitred. A big walnut tree grew close to the fence, and upon the limbs of this tree were some huge, shapeless knots; knots with convex backs and drooping tails; turkeys! The eyes of the starved raider glowed green and blue. Here was a feast. Strength for her, and life for her little ones back in their rocky den, crawling blindly about and wailing piteously for food. Softly as a moonbeam she crept forward, then came to a halt in dismay and sank upon her haunches. The plank with strips nailed across it, by the aid of which the turkeys gained their roost, had been removed and lay there upon the ground before her, to mock her baffled hopes and her bitter despair. With a keen sense of distances, she measured with her eye the height of the lowest limb from the ground. It was not far; she had made greater leaps time and again. But now her leaden, paralyzed limbs could scarcely carry her pinched body over the ground. To make the effort would be suicide. The dog-pack were sleeping somewhere near by, and their sleep was light! A cracking twig would rouse them, and that night she could not lead them. There were babies at home who needed her; she dared not make the attempt. One of the knots on a limb moved cautiously, then toppled. The watcher sprang forward eagerly, to again meet with disappointment. The sleepy wings flapped once or twice, a new footing was secured, and the head of the restless turkey receded into the neck feathers as the fowl relapsed into slumber. After a few moments the dull red shadow on the ground moved on again, hunger-mad, yet crafty. Into the confines of the yard crept the fox—up to a long, tall bench by the kitchen door. The scent of something strangely like fresh meat had reached her. There was a vessel of some sort covered with a piece of wood on the bench. To leap up and muzzle off the cover was the work of a second. And there was the dressed carcass of a chicken soaking overnight to serve as a breakfast for the human-people in the morning. Quickly as a star twinkles she of the forest-folk had the spoil in her strong jaws. Softly as a shadow falling she dropped to earth; swiftly as the wind she glided through the long corn rows growing in the garden back of the house, and was soon a mile away, safe, because unpursued. Then she sank upon her belly, and ate, and ate. Crunched the tender bones and the juicy flesh, impregnated as they were with salt, and gradually she felt the glad elation of returning strength. Through her worn, famished body renewed life was running, although the edge of her hunger had barely been removed. She lay quiet for a while, gathering together the taxed forces of her being, and thinking of the miles stretching between her and the little ones. But before the shadows upon the hill-tops turned into the misty halos of morning, six tiny forms lay at their mother’s breasts, well-fed and asleep.

Now another day had come and gone, and she was as bad off as before. Her mate, who had bided with her until the babies came, had tired of her and gone to seek a fairer wench, leaving her unaided to provide for the offsprings of their wild, free love. She had planned and worked, plotted and slain. The floor of the den was covered with feathers and sprinkled with broken bones—dry bones which she had cracked in desperation while searching for sustenance. It was a fight all the time. Fight for food; fight to live. So when the night had barely come, and the salmon tints in the west were yet a shadow, the she-fox nosed her importunate progeny into a whining heap at one side of the den and slipped softly without and moved down the hill-side, her waving tail like a smouldering torch in the gloom of the woods.

Keeping in the shadow of the rickety rail fence till it could no longer serve her, she halted a moment for deliberation, then twisted her supple body and half leaped, half crawled through a crack near the bottom. As she had stood with ears alert before veering her course, the faintest kind of tone had come to her. It was different from the hill-voices. The forest-kind know all the dozens of low noises which float along the knob-side at night. The voices and sounds are all soft—peculiarly soft. Only when a wild-cat is at bay, or the pack swings mouthing over the lowlands and the hills, is the wonderful silence of that region disturbed after the sun has gone. If her ear was not at fault—and privation had sharpened all of her faculties—the she-fox knew that a rich reward would soon be hers. Skirting the creek till she came to a place where it narrowed, she leaped across, and moved on in the same steady trot through the blackberry and sassafras bushes. Behind a low tangle of weeds and vines she crept at last, and crouched not three feet from a narrow hog-path winding on towards the farm-house half a mile away. From the pond at the base of the slight elevation over which the path led, some belated geese were ambling homeward. A half dozen or more; awkward, matronly, placid, moving in Indian file with never a thought beyond dipping in the hog-trough in the barnyard, or gobbling up the food thrown to the chickens. The webbed feet plodded on—straight to death. One, two, three, four—six plump bodies marched sedately by the low clump of matted weeds. Destruction swift and sure seized the last. Out of the shadows sprang a shape; two sinewy forelegs glided around the long white neck and skilful fangs tore open the portals of death. It was done almost without a sound. A feather or two and a few drops of blood were the only traces of the deed. Taking the blood as it gushed from the gaping wounds, the fox seized the neck firmly at a point near the base, slung the heavy body across her back with a dexterous jerk of her head, and started for her den at a swift lope. That night she feasted to repletion, and the next day she gorged herself on her kill. Made indolent by gluttony, she did not leave her lair for two whole days. Then her old enemy, hunger, returned again, and drove her to action.

During the days she had been lying inert in her rocky chamber, some things had happened which disturbed her not a little. The morning following the night she had brought in her prize, she had heard the dread voices of the hounds on some far-off range. All day, at intervals, the unwelcome chant had come to her ears, and so she knew that the human-people had missed their goose, and were abroad with the pack in quest of its destroyer. The second day a more alarming thing had happened. It was when the shadows of the taller trees began to lengthen towards the east, and twilight reigned in her cave home, that she was roused once more by the determined notes of the pursuing pack. Creeping to the entrance, she presently saw the chase passing along the knob-side. A great gray fox, nearly spent, was gliding, falling down the incline, his red mouth stretched for breath, and his bushy tail drooping. After him raced the hated friends of the human-people, loud-tongued and tireless. The gray fox was leading bravely, and hunters and hunted passed from view to the accompaniment of rustling leaves and snapping twigs and triumphant bays.

The next morning, near midday, her merciless offsprings teased and worried her so that the she-fox crept forth in spite of the warning of the day before, and set her sharp muzzle towards the crest of the range, with the intention of invading territory which hitherto her feet had never pressed. There were wild turkeys back in the hills, and wary and suspicious as she knew them to be, they were no match for her wily woodcraft. But scarcely had her noiseless feet gone over the top of the knob, when a sharp yelp immediately behind her caused her to jump and turn quickly. They were there—her enemies—and their noses were smelling out her trail, for as yet they had not seen her. Even as she leaped for the nearest cover like a yellow flash, her first thought was of the little ones biding at home. She must lead her foes away from that cleft in the rocks where her love-children lay awaiting her return. And though her life should be given up, yet would she die alone, and far away, before she would sacrifice her young.

It was a hard and stubborn race which she ran for the next six hours. At times her loyal, loving heart seemed ready to burst from the strain she thrust upon it. At times fleet feet were pattering almost at her heels, and pitiless jaws were held wide to grasp her; then again only the echo of the stubborn cry of her pursuers reached her. She had doubled time and again. Once a brief respite was granted her when she dashed up a slanting tree-trunk which, in falling, had lodged in the branches of another tree. Eight tawny forms dashed hotly, furiously by, then she descended and took the back track. Only for a moment, however, were the cunning dogs deceived. They discovered the artifice almost as soon as it was perpetrated, and came harking back themselves with redoubled zeal. So the long hours of the afternoon wore away. Not a moment that was free from effort; not an instant that death did not hover over the mother fox, awaiting the least misstep to descend. Back and forth, around and across, and still the subtlety of the fox eluded the haste and fury of the hounds. All were tired to the point of exhaustion, but none would give up. The sun went down; tremulous shadows, like curtains hung, were draped among the trees. The timid stars came out again and the halfed moon arose, a little larger than the night before. And still, with inveterate hate on the one side, and the undying strength of despair on the other, the grim chase swept through the night. At last the blood-rimmed eyes of the reeling quarry saw familiar landmarks. Unconsciously, in her blind efforts, she had come to the neighborhood of her den. Perhaps the love within her heart had guided her back. She found her strength quickly failing, and with a realization of this her scheming brain awoke as from a trance, and drove her to deeper guile. Two rods away was the creek. To it she staggered, splashed through the low water for a dozen yards, and hid herself beneath the gnarled roots of a tree from the base of which the stream had eaten away the soil. She listened intensely. She heard the pack lose the scent, search half-heartedly for a few minutes, for they, too, were weary to dropping, then withdraw one at a time, beaten. But for half an hour the brave animal lay against the tree roots, waiting and resting. Then she came out cautiously, looked around her, and with difficulty gained the mouth of her den. Casting one keen glance over her shoulder through the checkered spaces of the forest, she glided softly within, and lying down, curled her tired body protectingly around her sleeping little ones.

THE ROBBER BARON

THE Robber Baron sat upon his throne—for he was also a king. No courtiers attended him; no pages hung upon his slightest gesture. In dignified solitude he sat, and watched, and watched, and watched.

Part of the country through which Green River runs is almost as it was when the Master left it with the seal of completeness. Its topography is unchanged except for the natural changes brought about by the primeval elements of wind and water. There are vast stretches of timbered country checkered with cultivated acres, and rugged limestone cliffs fringed with moss and garlanded with poison ivy. The home of the Robber Baron was on the edge of one of these timbered tracts, in an old oak tree. This was his castle, and his alone. None of his feathered cousins dared perch in the spreading branches, even to rest for a moment. That tree was the property of the Baron, and he had proven his title to complete ownership more than once with beak and claws and beating wings. At the very top of the tree a dead snag shot up a distance of ten or twelve feet. This was the turret of the castle—the watch-tower. On its summit the old hen-hawk would perch, and complacently view his wide domain and his trembling subjects. And he was indeed a king. He levied tribute from the air, the earth, and the water alike, and whenever he poised and swooped, a life went out. One sound only caused his warrior heart to quake, and that was the solemn voice of the great horned owl, crying dismally in the night from the recesses of the wood. Here was a foe worthy of his steel; bigger, stronger, and bulldog-like in his battles. But the hawk took care not to pit his prowess against the power of this night marauder. During the day he was safe, for his one enemy who could wage successful warfare with him moped on a limb from sunrise till after dusk. In the darkness he sat high and safe, for the night-bird hunted low. More than once the Baron, sleeping the sleep of the gorged glutton, had awakened to the sound of mighty wings winnowing the air, and he would draw his fierce head a little further down between his wing-shoulders, shuddering and afraid. And if the night was moonlit, and he happened to look down, he would see a broad, black shadow gliding swiftly between the trees—a veritable spectre of death.

Day after day the Robber Baron sat on the top of the snag in the oak tree. This was his home, his bed, his point of lookout, and his banquet chamber. With almost telescopic keenness of vision, he could see what was going on for incredible distances around him. A rabbit’s quiet movements while feeding a half mile away on the young clover in a brown stubble-field; the neutral tints of the prim little quail as they scurried over the saffron leaves and through the yellow grass; a squirrel’s bark back in the forest behind him; a leaping fish in the stream which ran a good mile from his gray snag—all this he saw and heard, as well as many other things. If he had recently dined and was well filled and comfortable, he would ruffle his wings, preen his breast feathers, and gaze calmly upon the things which were his. When he wanted them he would go and get them, and when once those needle-pointed talons touched fur, feathers, or fins, they never let go their hold until they reached the snag. Then one foot would seek the familiar grasp, while the other held the victim down rigidly until the rending beak of the spoiler had torn out the life of his prize.

Now years of rapine and plunder and slaughter had not only schooled the Robber Baron in the fine art of taking game of every description, but it had made him an epicure as well. For, sailing over a barnyard one day, he saw a plump pullet dozing in the warm dust by the side of a stone wall. The instinct imparted by some daintily fed ancestor awoke, and hardly knowing it, the hawk swooped and clutched. There was a terrible outcry from the stricken pullet, and the barnyard tribe joined in the row with one voice. The pullet was fat and heavy and struggled desperately, but the sinewy pinions of the attacker had never failed him, and he slowly arose, with labored flapping, taking his captive with him. But the hubbub had reached indoors, where the farmer and his sons were taking their noonday meal, and to them the fuss outside meant “Hawk! Hawk!” and nothing else, for hens never cackle at any other time as they do when a hawk or a mink invades their midst. So a boy rushed out with a gun, and there, barely clearing the tops of the trees in the orchard, flew the raider. The boy fired twice, but when he ducked his head to gaze under the smoke, the hawk was still going, and with him the pullet. The shot had whistled about the ears of the Baron, and a hot streak had run up his back and across his neck, but no shot struck him fairly, and he went grimly on. When he at last sighted his tower his strength was giving down, for his burden was heavy and the way had been long. But he went up, up, bravely up, breasting the clear air higher and higher, and finally his feet rested on the old familiar place, and he skilfully balanced himself with his wings.

As he feasted, he realized that he had made a great discovery. The tender, juicy flesh which entered his greedy mouth in tempting strips was far more suited to his palate than was the meat of the wild things upon which he had hitherto preyed. All of the wild flesh was tainted, more or less, with the exception of the luscious quail, but here was something fit for even his kingly beak. So as he ate, he planned, and his thoughts boded ill for the farm housewife.

Thus it happened that for a time a feeling of peace and security reigned in the dominion of the king. In the rabbit world the cotton-tails came more and more into the open, venturing out from the brier patches and the low-growing bushes which were their natural protectors; but they never failed to watch the air with one eye while they ate, for the destroyer came silently, and the first warning was the fatal shadow falling upon them, followed by the smothering swish of wings. Then woe to the long-eared luckless one who was even a few feet from cover. The descent of the bold robber was like a lightning bolt—as swift and as deadly. The quail began to trot with more confidence between the stubble-rows—for it was the autumn season—and to hunt for berries and stray grains of wheat with less fear. So with all the different families over which the Robber Baron held sway. Every day a broad, thin shadow would pass over, but it never dropped, and the timid ground-people whispered to each other that their dreaded enemy had found a new hunting-place, and rejoiced accordingly. At times they saw him returning, nearly always flying low and heavily, with a cumbersome prey in his clutches. What it was, they did not know, but so long as he left them in peace they were content not to question his doings.

One golden afternoon the Robber Baron sat upon his turret in majestic loneliness. He was a royal bird. His head was flat; his brow niched and frowning, and his beak was curved like a boat-hook. His mighty wings were folded closely to his sides; his gray-white breast, flecked with brown, bravely met the winds which blew about his towering snag. His sturdy legs were tufted to the second joint, and his scaly talons, black and steel-like in their powerful grasp, curved firmly around the dead wood which formed his perch. He was a type of strength and grace, and the embodiment of rapacity and cruelty. Calmly and proudly his bold eyes roamed far and wide, resting for a moment upon a waving, irregular line of sedge, caused by the passage of some four-footed thing; then being drawn to the glinting breast of the river, where some constantly widening circles showed the upward leap of a frolicsome fish. But no heed at all did he pay to these signs, which upon other days would have lured him to pursuit. His aristocratic taste would no longer admit of such petty sacrifices and such poor food. Were not the feathers of a plump hen even at that moment littering the ground at the foot of his castle, and had he not heard, the night before, a prowling raccoon crunching the bones which he had disdainfully cast aside? The air was crisp with the tang of wild leaves which the frost had bitten, and hazy with the Indian summer glory of the season. Back in the forest behind him some maples were blazing in their crimson garments, and the hardier leaves of the oak and chestnut were tingeing. A creeper, encircling with many a close embrace the trunk of his own high tree, burned like the fiery serpent of some magician. Emboldened by the truce which their lord had declared, the Bob Whites sent their inexpressibly pure notes from different points like the sounds of answering bells. In the corn-field just across the river some men were working. With long knives in their hands they attacked the serried ranks of yellow-uniformed soldiery, and wherever they went they left a gap. Round pumpkins, which the Midas hand of frost had turned to purest gold, were being carried by others to one huge pile, forming a pyramid of plenty from the bountiful Giver. In a hickory tree near his castle two old crows were engaged in a very silly dispute, and the Baron turned a disgusted gaze upon the quarrelsome black things, who knew nothing of dignity, and all of sly theft. Far overhead a buzzard sailed along—that dumb, faithful scavenger of the wild, who was never known to utter a sound from the beginning of time. Him the big hawk respected. He attended to his affairs, and never engaged in bickerings with his neighbors. That he nested on the ground—in the caves and in the hollows of rotten tree-trunks—was no concern of the Baron, who scorned the earth, and never touched it but to rise again immediately.

The sun was slowly dipping towards a line of hills far to the west. The watcher on the snag took note of this, as he did of everything that went on around him, and he knew that if he was to have a feast that day he must go about procuring it. The barnyard which had been supplying him with his daily meal for the past ten days was not far away, but the wily robber had become used to many things during his predatory existence, and one of these things was that every house possessed a gun, and that a gun has a remarkably long range when loaded for hawk. During his last raid he had lost some feathers, and there was a constant, itching pain in one of his thighs, where a shot had lodged. He had tried to pluck it out with his murderous beak, but his efforts had only aggravated the wound, with the result that he was continually irritated. He would visit that barnyard no more. Sweeping his bold eyes in another direction, he beheld, several miles away, a wavering column of smoke ascending. This came from the chimney of a farm-house. He made his resolve quickly. The memory of countless repasts forbade the idea of even a day’s fast. The clamped toes unclasped, clasped, and unclasped again; the graceful body leaned forward, and the wing feathers quivered. Squatting low, the big bird launched himself in air and the broad wings shot out and bore him up. Once again he was in the element he loved.

The tiny hearts of the ground-people shook with fear as the shadow of the destroyer passed over the stubble-field, for weeks of immunity from attack had not lessened their fear of their bloodthirsty ruler. But the shadow passed on and disappeared; the river’s placid breast mirrored his image as the great hawk sped on, flying leisurely, for he would need his strength upon his return. Then over the corn-field, where the men were husking the yellow grain. Just over the variegated floor which the tree-tops of another forest made he passed on his flight, for there was no reason to mount high, and thus tire himself. Very soon the farm-house came in sight, and in the big yard was a grove of locust trees. These afforded an excellent shelter from which to spy, and presently his feet gripped a limb, he tilted forward from the momentum of his flight, but regained his equilibrium instantly, and his searching eyes turned this way and that in quest of a victim. About the yard some matronly hens were straying, with here and there a strutting cock, self-conscious and pompous. The daring robber did not hesitate long. A particularly tempting Plymouth Rock hen drew his eye, and instantly he left his perch, arose in the air, and prepared to swoop. Just as he closed his wings for this purpose, a babel of twittering arose which he had learned to dread, and around the corner of the house sped two martens with fluttering wings and wild cries of anger. Dismayed, the marauder spread his wings again and strove to escape, while a fearful tumult began among the fowls in the yard, followed by a wild rush for cover. Swift of wing and fearless, the tiny attackers vigorously pursued the fleeing hawk, hovering over him with their shrill cries, and now and again dropping upon his back to deliver a sharp peck. When they had chased the invader from the yard they considered their duty done, and came back in wild curves to their box on the pole in the rear of the house.

Enraged and smarting from the chastisement which he had received, the hawk sailed up in a white ash tree to rest and consider the situation. As he debated dusk came on, and he became aware that he was desperately hungry. The yard was guarded, and he could not enter there. Disappointed and sore, he was preparing to depart empty-handed, when his restless eye caught sight of a dark spot moving over the ground not far away. It was a foraging hen coming home to roost. Five seconds later his pinions hissed over the head of the doomed fowl, the knife-like talons caught and held, and he painfully arose to begin his homeward flight. His prey was a full-grown hen and was heavy as lead, but when he arose with his spoil he never let go his hold. So over the tops of the trees he went again, the limp body in his grip brushing some of the leaves, so heavily did it sag. Back over the corn-field, forsaken now by the harvesters, and his flight was so low that a man with a club might have struck him. Then the river, in which the first stars were beginning to gleam. How his legs ached, and each motion of his wings wrenched his body. He had never been so late returning before, and the distance had never seemed so long. On the other side of the stubble-field rose his tower, waiting for him to come home, as it had waited through all his life. Would he ever reach it? He would if it cost him his life, for he could not sit on the earth and eat, like a filth-devouring buzzard. His dragging flight over the field was more than half completed, when he heard a sound that turned his blood to ice. It was the deep, solemn note of the horned owl, boomed forth at the edge of the wood. He had tarried too long at his hunting, and his enemy was coming on his night-hunt for food.

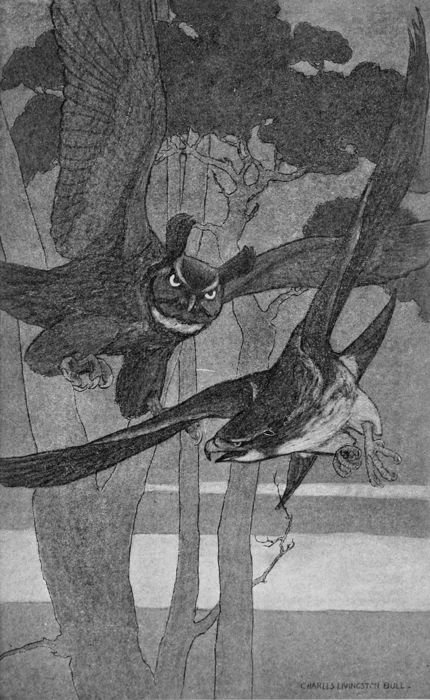

“Zigzagging nimbly, he strove to elude his pursuer.”

Swiftly the hawk dipped and swerved, but those big red-green eyes, to which darkness was day, beheld him, and gave chase. The wily robber dropped his burden, hoping to bribe the spectre in his wake. But with a rush the owl passed over the cast-off carcass, and sped on. The hen-hawk heard the soft, feathery wing-swish coming nearer and nearer, and though he was no coward he knew that his hour was at hand, for he was worn and spent, whereas his foe had fresh strength. Zigzagging nimbly, he strove in this manner to elude his pursuer. But the big owl had waited long for this chance, and he was resolved that it should not escape him. Suddenly he struck out with beak and claws, and the hawk careened wildly from the shock, then righting himself, turned to give battle—it was the last resort. And so they clashed and clashed again. There arose the rasping of beak on beak and the dull thud of flesh propelled against flesh. Feathers were torn out by clawfuls, and the breast of each combatant was streaked and dabbled with blood. At last the owl, maddened and all-powerful in his might, beat and smothered his antagonist to the earth, and holding that kingly head on the ground with the vise-like grip of one foot, with his curved beak he prodded and tore till life was gone from the Robber Baron.

The gray old snag which was his tower waited for his coming that night in vain.

Illustrator: Charles Livingston Bull

If you want to read more or use CLICK ON LINKS

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/56430/56430-h/56430-h.htm

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/56430

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/56430/

If you like the book and want more, please, support me.

I just read first para of this post. I think this book will be very informative in our life. I will read later in my leisure time. so I just copied and kept this link.

Your response is very appreciated in your other post. so I just upvoted you and I also follow you to get your next post.

but, if you also, are an artist Gutenberg is great.

http://www.gutenberg.org/wiki/Main_Page

Interesting. Great job you were working hard in this post. Your hard work show in the post.🖊🖊🖊🖊🖊🖌

I've been sick for over 6 months and finally came back to STEEMIT!

I try to what i can and use this as a program for my fingers.

This is old . . . .that is why it's free. Follow the link and read the rest

or download it for your projects. You d0n't have to credit but it's nice.

Thanks and i hope your experience and great job, will growth your position and reputation. Best of luck my friend 😙😘😙😘

I like your picture and all the work on your comment.

Always take the time to do your best and

you'll stand out and be different. Never beg.

You @praveenposwal have dignity!

My college (B.sc 2nd) after 20 days so i will not spend extra time in steemit.

I'm understanding. I will believe you my next post i make my fingers and thus credit only ................

✉

It is suitable for the love of reading.

Gutengurg has thousands of book and zines.

All are public domain/free.