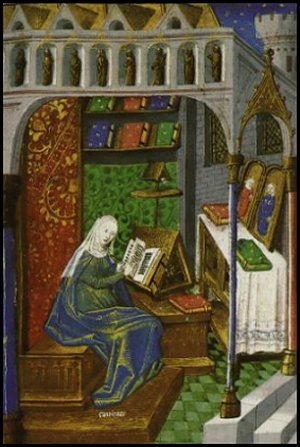

a depiction of Hedewijch

image source

and I can desire freely with my will,

and I can will as highly as I wish,

and seize and receive from God all that he is,

without objection or anger on his part

- what no saint can do.

~ Hadewijch(1)

The author Rosalynn Voaden (1999) defined a ‘mystic’ as being very intellectual – as opposed to a ‘visionary’ who was very spiritual – and that mysticism was characterised as being unio mystica. The experience supposedly encompassed all a persons senses as they felt a powerful one-ness with God during those moments of communing. Patricia Dailey (2006) adds to unio mystica the characteristics of imitatio Christi and vita apostolica as the possible qualities shown by a mystic. At times, the terms ‘mystic’ and ‘visionary’ may be interchangeable, or used in conjunction with each other when describing a woman’s experience(s). The basis of the authority claimed by medieval women mystics for the public articulation of their mystical experiences included their feelings of credibility in their direct interactions with God, confidence that they were not alone in their experiences, validation from external sources, and their direct communications with God (or Jesus) himself.

According to the historian André Vauchez, who gathered statistics on female lay saints, ‘55.5 percent of women among the laity [were] canonised during the Middle Ages, and […] 71.4 percent of women [were] among lay saints after the year 1305’,(2) but when looked at as part of a whole picture, those figures came from a very small base number of people, and that in fact it was less likely that these women would be accepted by their peers and wider community than considered outcasts, insane, possessed or otherwise treated with suspicion. We can then see why it would have been quite an ordeal to step forward and publicise their mysticism. There were great obstacles for women to be seen by men as being equally worthy of ‘religious experiences’, let alone being able to articulate them or be taken seriously by the majority of Christians, by the mere fact that they were women. Their traditional role, as taken at face value within readings from the Bible, placed them as subordinates to men and therefore unable to obtain equality with God:

But I would have you know, that the head of every man is Christ; and the head of the woman is the man; and the head of Christ is God…The man indeed ought not to cover his head, for he is the image and glory of god: but the woman is the glory of the man.(3)

It was not only the christian’s Bible or Western European cultures that appeared to have misogynistic advice. According to the Palestinian Talmud ‘it is preferable to burn the words of the Torah rather than put it into a woman’s keeping’;(4) and Philo of Alexandria, who was a Hellenised Jew, attributes to women the bringers of ill fortune and sin – beginning with Eve, of course, but continuing with every other woman since – to man “… [a]nd woman becomes for him the beginning of blameworthy life”.(5) Those and other similar ideals had certainly not originated in the Middle Ages, the influence of the Classical age was clear.

Aristotle, Augustine, Galen, and Pliny the Elder were several classical-age male advocates of women being held in such negative regard whose influences were felt even hundreds of years later, the result being that their views were advocated within the Church doctrine. Apparently women had a ‘natural inferiority’. They were also seen as not being able to control their sexual urges and tempting men into mischief – Bernard of Clairvaux stated that “it is easier to raise the dead than to be constantly with a woman and avoid intercourse’(6); the natural functions of their bodies were supposedly flawed, and unclean, which meant keeping them from areas within, or rituals of, the church during certain phases of their lives. This sort of control men exercised over women would have overflowed from within the Church system into their everyday lives, with the majority of women being prevented from being treated as equals socially, politically, economically or culturally. Women who wanted to break out of the mould had great obstacles to overcome from their peers, let alone surmounting the self-doubt they went through to believe they were actually having mystical experiences with God, let alone believing they were worthy of the experiences, before even contemplating verbalising those experiences to their peers and subjecting themselves to close scrutiny.

What the Church looked for was credibility, and ‘[t]o be credible, a visionary must be presented as authorised by both divine and ecclesiastical powers.’(7) In essence this meant that all incidents had to conform to the doctrine of discretio spirituum – the ability to distinguish whether the spirits seen during the episode were sent by God or the devil – and pass through clerical channels for ecclesiastical sanction. From all accounts, all clerical channels are thus masculine, so there is still a patriarchal dominance and a feminine submissiveness in place. Outside of religious doctrine, from all evidence it also appears to be that while the women were sanctioned in their mysticism and visions that did not mean they would or could explore levels of power outside their given societal places. Perhaps they had no interest outside ecclesiastical matters, but even within the Church they appear to not have had any thoughts on challenging the rules on the feminine place in religion – except for perhaps Margery Kempe, who did appear to challenge the clerical authority over some small matters, such as when her bishop told her she could not wear white clothing as a symbol of chastity(8) as she was a married woman and had borne children; but greater feminine versus masculine societal issues do not appear to be challenged. Over time, being a feminine mystic became a little easier as more and more, spiritual women were being venerated by the Church, which in all probability made it easier for women mystics to be accepted within society, at least in part. In cathedrals and churches, on dossals and frescoes, as statues, on lintels, and on stained glass windows could be found depictions of not only Eve and Mary, but female saints and angels, biblical women, and even the laity – not only church donors but ‘ordinary’ women in everyday scenes. ‘Women […] were inescapable, visible, and sometimes even dominant in the great cathedrals and parish churches of the Gothic period.’(9) Women also began to appear in illuminated manuscripts and were represented in liturgical dramas. The women were represented as being admirable, noble, virtuous, pious, and as having other respectable qualities that would give inspiration. Being surrounded by feminine aspects of religion must have acted on some at least sub-conscious level in the minds of people to be more open to accepting the ideas and visions of the women mystics.

Also perhaps, hearing of other female mystics may have given a woman courage to publicise her own mystical experience(s). The author Bernard McGinn noted that there was a ‘visionary explosion’ during the later Middle Ages, ‘especially among women’,(10) and perhaps even if that upsurge included men, then by the mere volume of documented mystic experiences the women may have felt more comfortable and less alone in their experiences. Margaret of Cortona was apparently given a visionary experience whereby she saw in her future that she would become a saint, and this gave her a ‘sense of her own importance’(11) and likely gave her the confidence to seek admission into a Franciscan order for protection and penitence. For Juliana of Mont-Cornillon it was apparently Christ himself who commanded her that “once every year, the institution of the sacrament of his Body and Blood should be recollected more solemnly and specifically than it was at the Lord’s Supper” and that she should be the one to “inaugurate this feast and be the first to tell the world it should be instituted”;(12) although it took Juliana twenty years to gain the courage to really begin the process, but the feast did become established in 1246, as the Corpus Christi, and developed into a very popular annual ritual. But, for Juliana, confidence that she had the authority to publicly articulate came when “the bishop of Liege, who cherished Juliana for her exceptional holiness, ordered that a new oratory should be built for her” and so “many religious people and dignitaries flocked there to commend themselves to Juliana’s prayers, edified by what they saw in her and heard from her lips”,(13) certainly making for a positive ecclesiastical endorsement.

Another reason behind the women mystics’ confidence about speaking out publicly was likely because of the experiences they felt were from or with God. It appeared to be something that could set them apart from other lay or ecclesiastical peoples’ religious experiences. For the mystic it was possibly not something they could verbalise well, but more of an ‘unmistakeable knowing in the soul’.14 Teresa of Avila had great confidence she was communing directly with God:

I used unexpectedly to experience a consciousness of the presence of God, of such a kind that I could not possibly doubt that He was within me or that I was wholly engulfed in Him. This was in no sense a vision: I believe it is called mystical theology.(15)

These women were extremely confident that their experiences were from God, although they might often feel moments of self-doubt as to why they were singled out, as they saw it, by God for their mystical experiences. Women such as Maria de Santo Domingo were given a high spiritual status, and even though she was accused of heresy, her confessor saw in her a ‘spiritual potential’, and admitted that her mystical experiences went beyond any of his experiences. At Maria’s trial he testified that he’d experienced ‘a degree of fervour and repentance that he had never felt before’(16) and in a Medieval world dominated by male hierarchies that would have been high admiration indeed. Maria’s confessor was not alone, however, in his views of a much more equal balance between men and women in a religious context, even if it was given possibly as a rather ‘backhanded compliment’.

Meister Eckhart, the German theologian, insisted that ‘God could be found, directly and decisively, anywhere and by anyone’(17) which implies an equality across the sexes and a positive reinforcement for the authority of women to publicise their mystical experiences. Being a mystic himself, there was obviously no sense of ‘competition’ between the sexes for him in this regard. Henry of Ghent, around 1290, said that women could not teach by ‘ecclesiastical approbation’ but there was no reason they could not teach ‘from grace’ and that “speaking about teaching from divine favour and the fervour of charity, it is well allowed for a woman to teach just like anyone else, if she possesses sound doctrine”.(18) This non-scholastic, non-monastic form of teaching by the layperson was known as ‘vernacular theology’, and encompassed not just ‘unqualified’ women, but men also who had a great passion to spread and teach with ecclesiastical authority, even without ecclesiastical qualification. Apparently, several women mentioned in the Old and New Testaments of the Bible were ‘all chosen by god to be prophets’(19) and that prophesy was a ‘special grace’, although there were still restrictions such as having to cover their heads. ‘Visions and prophesy provided them with an arena where they were authorised, through scripture, to operate with some degree of autonomy or independence.’(20) Supposedly in a vision, God told Hildegard of Bingen that ‘while women cannot administer the sacraments, those who have dedicated themselves to Christ can experience union with him’(21), suggesting a complimentary role to the priest for the woman mystic. She was also to find herself stepping into other roles of responsibility, those of author and public orator.

During both the twelfth and thirteenth centuries an argument was put forward regarding the right of women mystics to publicise their experiences, in that ‘if God chose to give women visions, to bestow prophecies on them, or to render himself one with them, then women might also be permitted – indeed even be called on – to speak and write of these things’(22) which then meant that these women, validated in their experiences, could go on to write, speak out publicly and even teach others, clear that they had a right to do so. And this was likely the only platform women had by which to gain a voice in such a patriarchal society, on any subject or matter. As it was unusual for a woman to be literate, and especially to know Latin rather than the vernacular written language, she had to rely on a man to make a written record of her mystical experiences, and it was still more common for a cleric rather than a layman to be literate and have access to the necessary equipment, there must have been some level of acceptance by the cleric towards the woman’s experiences as she dictated her thoughts to him. In fact, it may be that their hagiographers were the people most likely to venerate these mystical women. Playing important roles in her life, these men were also likely to have been a women’s confessor and spiritual advisor, and initial credibility-checker.

As these women struggled against not only self-doubt, but accusations of heresy and other harsh crimes, their convictions in what they were experiencing between themselves and the higher power of God, or perhaps Jesus or even Mary, helped them rise above all those doubts and nay-sayers. Not all of the women worked from within the Church, as the abbess Hildegard of Bingen, but as a layperson, like Margery Kempe who admittedly had a harder time proving her credibility to Church members because of her status. These women experienced such one-ness, such euphoria within themselves that they had a great need to share their mystic incidents with the world. In fact, Juliana of Mont-Cornillon was supposedly given by God a message for the Church, and although it took her many years to gain the courage to do so, she did manage to complete her task successfully. Many of the women managed to find men who would give them guidance, support and encouragement to use their voices out in the world, whether it was by written or oral means. This was also the only outlet by which women had a chance at having an equal and powerful voice amongst their patriarchal cultures. These women felt that the basis for their authority to publicly articulate their mystical experiences was their communion with the highest power, but perhaps the authority actually came from within each of them, as a validation of their own self-worth in the eyes of God.

a depiction of Margery Kempe

image source

This essay was one I wrote as an assignment, while obtaining my University degree. I have included the reference list and bibliography - reference materials I used while writing - just as I'd had to for its submission. It has never before been published anywhere public, though.

References

1 Ranft, Patricia. Women and Spiritual Equality in Christian Tradition. 1st ed. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998, pp. 159-160.

2 Caciola, Nancy. "Mystics, Demoniacs, and the Physiology of Spirit Possession in Medieval Europe." Comparative Studies in Society and History 42.2 (2000), pp. 270.

3 I Corinthians 11.3 and 7.

4 Voaden, Rosalynn. God's Words, Women's Voices : The Discernment of Spirits in the Writing of Late-Medieval Women Visionaries. York: York Medieval Press, 1999, pp. 21.

5 ibid., pp. 22.

6 ibid., pp. 28.

7 ibid.,, pp. 122.

8 Wilson, Janet. “The Communities of Margery Kempe’s Book” in Medieval Women in Their Communities. Watt, Diane, Ed. Toronto Buffalo: Toronto Press Incorporated, 1997, pp. 169.

9 Ranft, Patricia. Women and Spiritual Equality in Christian Tradition. 1st ed. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998, pp. 165.

10 McGinn, Bernard. "The Changing Shape of Late Medieval Mysticism." Church History 65.2 (1996), pp. 197.

11 Petroff, Elizabeth. "Medieval Women Visionaries: Seven Stages to Power." Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 3.1 (1978), pp. 34.

12 Ranft, Patricia. Women and Spiritual Equality in Christian Tradition. 1st ed. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998, pp. 174.

13 ibid., pp. 161.

14 Voaden, Rosalynn. God's Words, Women's Voices : The Discernment of Spirits in the Writing of Late-Medieval Women Visionaries. York: York Medieval Press, 1999, pp. 15.

15 Ranft, Patricia. Women and Spiritual Equality in Christian Tradition. 1st ed. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998, pp. 217.

16 ibid., pp. 217.

17 McGinn, Bernard. "The Changing Shape of Late Medieval Mysticism." Church History 65.2 (1996), pp. 199.

18 ibid., pp. 209.

19 Deborah (Judges 4.4), Miriam (Exodus 15.20), Huldah (II Kings 22.14; II Chronicles 34.24), Anna (Luke 2.36-8).

Voaden, Rosalynn. God's Words, Women's Voices : The Discernment of Spirits in the Writing of Late-Medieval Women Visionaries. York: York Medieval Press, 1999, pp. 37.

20 Voaden, Rosalynn. God's Words, Women's Voices : The Discernment of Spirits in the Writing of Late-Medieval Women Visionaries. York: York Medieval Press, 1999, pp. 37.

21 ibid., pp. 38.

22 Hollywood, Amy. Mysticism and Mystics. Women and Gender in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. Ed. Schaus, Margaret. New York: Routledge, 2006, pp. 596.

Bibliography

Women in England C.1275-1525. Trans. Goldberg, P.J.P. Ed. Goldbert, P.J.P. New York: Manchester UP, 1995. Print.

Women's Lives in Medieval Europe: A Sourcebook. Ed. Amt, Emilie. London: Routledge, 1993. Print.

Bennett, Judith M. A Medieval Life : Cecilia Penifader of Brigstock, C. 1295-1344. 1st ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill College, 1999. Print.

Caciola, Nancy. "Mystics, Demoniacs, and the Physiology of Spirit Possession in Medieval Europe." Comparative Studies in Society and History 42.2 (2000): 268-306. Print.

Dailey, Patricia. Mystics' Writings. Women and Gender in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. Ed. Schaus, Margaret. New York: Routledge, 2006. Print.

Finke, Laurie A. Women's Writing in English: Medieval England. Women's Writing in English. Ed. Kelly, Gary. Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman Limited, 1999. Print.

Goodich, Michael. "The Contours of Female Piety in Later Medieval Hagiography." Church History 50.1 (1981): 20-32. Print.

Hirsh, John C. The Boundaries of Faith : The Development and Transmission of Medieval Spirituality. Studies in the History of Christian Thought, V. 67. Leiden New York: E.J. Brill, 1996. Print.

Hollywood, Amy. Mysticism and Mystics. Women and Gender in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia. Ed. Schaus, Margaret. New York: Routledge, 2006. Print.

Leyser, Henrietta. Medieval Women: A Social History of Women in England 450-1500. London: Phoenix Press, 1996. Print.

McGinn, Bernard. "The Changing Shape of Late Medieval Mysticism." Church History 65.2 (1996): 197-219. Print.

Petroff, Elizabeth. "Medieval Women Visionaries: Seven Stages to Power." Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 3.1 (1978): 34-45. Print.

Petry, Ray C. "Social Responsibility and the Late Medieval Mystics." Church History 21.1 (1952): 3-19. Print.

Priest, Ann-Marie. "Woman as God, Goad as Woman: Mysticism, Negative Theology, and Luce Irigaray." The Journal of Religion 83.1 (2003): 1-23. Print.

Ranft, Patricia. Women and Spiritual Equality in Christian Tradition. 1st ed. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998. Print.

Rubin, Miri. "The Culture of Europe in the Later Middle Ages." History Workshop 33 (1992): 162-75. Print.

Thornton, Martin. Margery Kempe: An Example in the English Pastoral Tradition. London,: S.P.C.K., 1960. Print.

Voaden, Rosalynn. God's Words, Women's Voices : The Discernment of Spirits in the Writing of Late-Medieval Women Visionaries. York: York Medieval Press, 1999. Print.

---, ed. Prophets Abroad : The Reception of Continental Holy Women in Late-Medieval England. Cambridge Rochester, NY, USA: D.S. Brewer, 1996. Print.

Watt, Diane. Medieval Women in Their Communities. Toronto Buffalo: Toronto Press Incorporated, 1997. Print.

Wiethaus, Ulrike. Maps of Flesh and Light: The Religious Experience of Medieval Women Mystics. Syracuse UP, 1993. Print.

I am so glad thatvyou finally got curied fir your awesomly unique research!!!! I wish we could have gotten the Ray women too but i believe this is just the start of your epic reign in the history research tags. Also might be the first time curie approves a post tagged religion lololol . Great work!! #teamgirlpowa is lucky to have you on our team. ❤️❤️❤️❤️🦑❤️❤️❤️

I guess I will have to dust off my academic hat and dive into the research again. There is so much in history that is worth bringing to light. :)

I had NO idea when you suggested it that this would happen, so THANK YOU SO VERY MUCH for submitting it @limabeing, and another HUGE THANK YOU to the @curie team for feeling that it had something positive to contribute to Steemit. So glad I found #teamgirlpowa an amazing group. :D

I am Sharing Sahih Muslim Hadith on daily basis, please upvote and follow my posts, it will be surely useful for you and all the Muslim Community, I am sending the link of post:

https://steemit.com/religious/@teenauk/sahih-muslim-hadith-1-faith-kitab-al-iman

This was actually quite educational and interesting, because it is not really my area of expertise.

I'm glad you enjoyed reading it. It's really only a scratch on the surface of what isn't well known in history. :)

You mean the topic of women in history in general? What is worse is the scarcity of good sources.

Oh yes, very much so.

I was not aware of this before.This is a very good post to learn about it.You have done a great review of the history to write such a post.Well done

-cheers-

Thank you, I'm happy that you enjoyed it. The subject was certainly eye-opening. :)

thanks :)calling @OriginalWorks

To call @OriginalWorks, simply reply to any post with @originalworks or !originalworks in your message!

Great stuff. Thank you.

Good post, I am a photographer, it passes for my blog and sees my content, I hope that it should be of your taste, you have my vote :D greetings

Excellent

What an excellent, in-depth look at the history of female mystics (and their oppression). I especially like your closing line: "perhaps the authority actually came from within each of them, as a validation of their own self-worth in the eyes of God."

I just joined steemit (my intro post is on my blog), and am thrilled to see people like yourself being rewarded for quality content. What a revolutionary, empowering platform. I'm glad you published this here!

Thank you! I am very pleased you enjoyed it, and found it informative. Inspires me to try and create more - and yes I absolutely agree about the platform. When I joined I never would have guessed I'd be publishing articles like this and that there would be an audience liking them.

It's truly encouraging. :)

and I shall check out your blog now, too

Wow, love the whole research! Amazing! :D This is so educative and interesting :) thanks for posting :D

Thank you so much for taking the time to read it, and then enjoy it. I have been blown away by the positive responses, tbh. :)

Hello again, I would be very interested in your research/study of the agnostic cathars of southern France, before their genocide by the Holy Roman Catholic Church. Their mysticism was of a particularly interesting nature, compared to the more 'in the box' variety of regular church believers.

I might not vote here often, but I am reading and following. Keep on keeping on. 😇

I know I've read a bit on the Cathars during my research travels, so I might have a look at what you've mentioned.

I appreciate that you have enjoyed reading the posts, thank you for your support. :)

In Caboolture, every year for several now, at Abbeystow, they hold a Medieval Fair/Festival. People from all over Australia set up sites in a paddock, with everything from weaving to cloth-making, from Viking longboats to Moslem janissaries. There is jousting, toffee-apples, Turkish coffee, and Shuvani soul-dancers. Google Search. Unfortunately, I lost my Ph's backup in my laptop crash, and cannot access my ext hddv just at present, but there are many fine photos on internet. Abbeystow near Caboolture, near Brisbane, in SEQ.

Found it: https://abbeymedievalfestival.com/ Looks like a wonderful festival to get to experience.

I'm sure I've some photos, but my hddvs are off line, and until I can secure my laptop again, it's a bit of battle to get photos transferred. But maybe in a couple of days. I'm driving out bush tomorrow, so no computers. Unsure what I've backed up, but I will send some. 😑

Speaking of research, and hard to find sources. I'm not sure where, but the soul-dancers (Shuvani, {gypsy} [silk-road travellers]) have a dance class in Petrie, a town in SEQ. If you find them on www, their 'mater'/headwoman¿ might put you in the way of much silk-road 'women's history'.

Thank you for you post:)

Shouts out to Hildegard of Bingen!