Nearly 500 years ago a young Man called Étienne de La Boétie wrote a Book, about the way People live under the force of Tyrants and how they can free themselves.

The Politics of Obedience: The Discourse of Voluntary Servitude

Étienne de La Boétie (1530–1563)

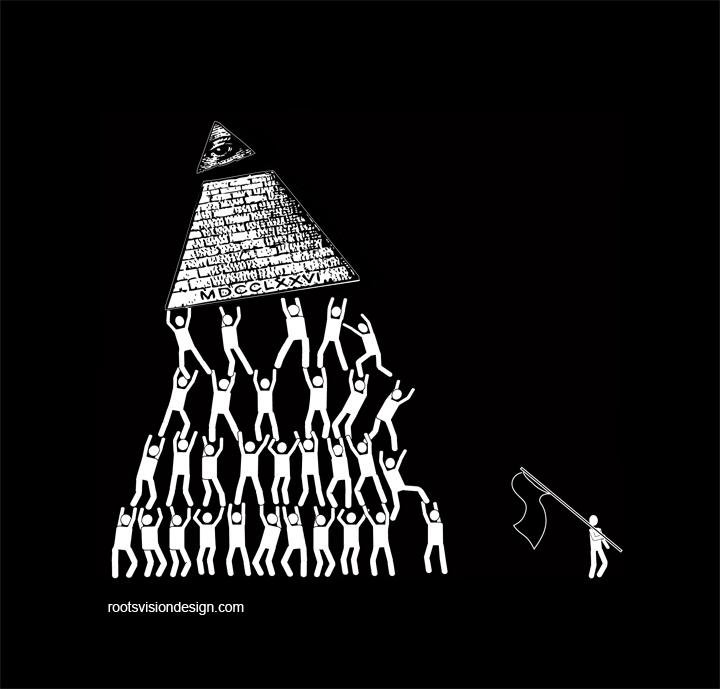

For the present I should like merely to understand how it happens that so many men, so many villages, so many cities, so many nations, sometimes suffer under a single tyrant who has no other power than the power they give him; who is able to harm them only to the extent to which they have the willingness to bear with him; who could do them absolutely no injury unless they preferred to put up with him rather than contradict him. Surely a striking situation!

I encourage you to read the whole Book , it's short but enlightened and well worth the Time.

https://mises.org/library/politics-obedience-discourse-voluntary-servitude

Here are my favorite parts :

They suffer plundering, wantonness, cruelty, not from an army, not from a barbarian horde, on account of whom they must shed their blood and sacrifice their lives, but from a single man — not from a Hercules nor from a Samson, but from a single little man. Too frequently this same little man is the most cowardly and effeminate in the nation, a stranger to the powder of battle and hesitant on the sands of the tournament — not only without energy to direct men by force, but with hardly enough virility to bed with a common woman!Shall we call subjection to such a leader cowardice? Shall we say that those who serve him are cowardly and fainthearted? If two, if three, if four do not defend themselves from the one, we might call that circumstance surprising but nevertheless conceivable. In such a case one might be justified in suspecting a lack of courage. But if a hundred, if a thousand endure the caprice of a single man, should we not rather say that they lack not the courage but the desire to rise against him, and that such an attitude indicates indifference rather than cowardice?When not a hundred, not a thousand men, but a hundred provinces, a thousand cities, a million men, refuse to assail a single man from whom the kindest treatment received is the infliction of serfdom and slavery, what shall we call that? Is it cowardice? Of course there is in every vice inevitably some limit beyond which one cannot go. Two, possibly ten, may fear one; but when a thousand, a million men, a thousand cities, fail to protect themselves against the domination of one man, this cannot be called cowardly, for cowardice does not sink to such a depth, any more than valor can be termed the effort of one individual to scale a fortress, to attack an army, or to conquer a kingdom. What monstrous vice, then, is this which does not even deserve to be called cowardice, a vice for which no term can be found vile enough, which nature herself disavows and our tongues refuse to name?

Place on one side fifty thousand armed men, and on the other the same number. Let them join in battle, one side fighting to retain its liberty, the other to take it away; to which would you, at a guess, promise victory? Which men do you think would march more gallantly to combat — those who anticipate as a reward for their suffering the maintenance of their freedom or those who cannot expect any other prize for the blows exchanged than the enslavement of others?

One side will have before its eyes the blessings of the past and the hope of similar joy in the future; their thoughts will dwell less on the comparatively brief pain of battle than on what they may have to endure forever — they, their children, and all their posterity. The other side has nothing to inspire it with courage except the weak urge of greed, which fades before danger and which can never be so keen, it seems to me, that it will not be dismayed by the least drop of blood from wounds.

Obviously there is no need of fighting to overcome this single tyrant, for he is automatically defeated if the country refuses consent to its own enslavement: it is not necessary to deprive him of anything but simply to give him nothing; there is no need that the country make an effort to do anything for itself provided it does nothing against itself. It is therefore the inhabitants themselves who permit, or, rather, bring about, their own subjection, since by ceasing to submit they would put an end to their servitude.A people enslaves itself, cuts its own throat, when, having a choice between being vassals and being free men, it deserts its liberties and takes on the yoke, gives consent to its own misery, or, rather, apparently welcomes it. If it cost the people anything to recover its freedom, I should not urge action to this end, although there is nothing a human should hold more dear than the restoration of his own natural right, to change himself from a beast of burden back to a man, so to speak. I do not demand of him so much boldness; let him prefer the doubtful security of living wretchedly to the uncertain hope of living as he pleases.

If you by now don't see the similarities with our current Time and Condition then i can't Help you ;)

"Liberty is the only joy upon which men do not seem to insist; for surely if they really wanted it, they would receive it. Apparently they refuse this wonderful privilege because it is so easily acquired."

If you liked what you just read you should read the Whole Book.

https://mises.org/library/politics-obedience-discourse-voluntary-servitude

I hope you enjoyed it and maybe you've learned a bit from it like i did.

PEACE , LOVE & ANARCH

Thanks for reading