If I've been a little quiet on Hive lately, here is why.

Set out below (so they are on-chain) are my submissions against Meta and Google's interlocutory application to stay or declass the proceedings (litigation tactics to try to avoid a hearing on the substantive issues).

I had only one week to prepare these submissions (after receiving Meta and Google's submissions) and they are 16,800 words.

They are so large that I've had to split them into three posts because of Hive blockchain post size limits.

If you want to see the stamped originals of Meta, Google and my submissions in PDF form they are available on the JPB Liberty website: https://www.jpbliberty.com/post/submissions-for-interlocutory-motions-from-meta-google-and-andrew-s-response

Apologies for the paragraph numbering re-setting at each heading - this is a Hive front-end rendering issue and is not how the text appears on the Hive blockchain or in the stamped original document.

Please vote for my Hive witness. (KeyChain or HiveSigner)

Witness Vote using direct Hivesigner

Andrew Paul Stuart Hamilton v Facebook Inc. & Google LLC NSD899/2020

Submissions of Applicant - Against Declassing / Stay

"FCAA" means the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

"CCA" means the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) and

"Part IV" means part IV of that Act. "FCr" means the Federal

Court Rules 2011 (Cth)."MAW - 2" means Exhibit MAW - 2 to the affidavit of Mark Anthony

Wilks dated 8 November 2022. "LFA" means JPB Liberty Pty Ltd's

Litigation Funding Agreement. "Conflicts Policy" means JPB

Liberty's Conflicts of Interest PolicyThe Applicant's Consolidated Submissions on Leave to

Serve dated 13 July 2021 ("ConSub") are incorporated in these

submissions.

Summary

The Respondents seek to stay or declass an important public interest

class action affecting the welfare of millions of Australians,

purportedly "in the interests of justice" (FCr 1.32 & FCA Act s 33N)

on the basis of alleged conflicts of interest and/or alleged

prohibited contingency fees arising from the litigation funding

arrangements.There is no authority allowing proceedings in which the jurisdiction

of the Court has been regularly invoked to be stayed on this basis.Conversely binding High Court authority:

permits a broad range of litigation funding arrangements,

despite substantial inherent conflicts of interest (far greater

than those here)[1]; andprovides that a plaintiff who has regularly invoked the

jurisdiction of a court has a prima facie right to insist upon

its exercise[2]; andholds that the jurisdiction to grant a stay is to be exercised

"with great care" or "extreme caution"[3].

The litigation funding arrangements in these proceedings are

superior to typical class actions funded by large litigation

funders, both in having far less conflict of interest and providing

a more efficient and economic method for the group members to pursue

their claims.It is entirely disingenuous and perverse for the Respondents to

assert[4] that the Court, in exercising its protective jurisdiction

over group members[5], should effectively extinguish the rights of

those group members to obtain remedy for the Respondents unlawful

and highly damaging conduct. The Respondents have no genuine

interest in protecting the rights of group members and instead

engage in unmeritorious litigation tactics to attempt to deprive the

Applicant and group members of their right to be heard on the

merits.Binding Full Court authority limits the use of the FCAA s 33N

declassing power to situations where multiple individual proceedings

would be more in the interests of justice than the actual

representative proceedings on foot[6]. The section requires the

comparison between these two scenarios only, on the four criteria in

s 33N (a) - (d). It does not provide a general power to declass

because of alleged conflicts of interest arising from litigation

funding arrangements.Declassing is clearly not in the interests of justice, particularly

the efficient administration of it, in the current situation where

millions of people have legally identical claims against the

Respondents at the liability stage. This is particularly the case

when a large percentage of the group members have claims which are

too small to be economic to pursue individually.In circumstances where the Court has already determined[7]:

a prima facie case exists, and has clearly set out that case;

there is a substantial public interest in the proceedings,

including as private enforcement of Part IV of the CCA;that the public interest in Part IV enforcement is enhanced by

the proceedings being representative proceedings,

the over-riding interests of justice require the Court to hear and

determine the Part IV claims on their merits as representative

proceedings.

A public interest strong enough to override an exclusive

jurisdiction clause[8] is strong enough to override any issue

arising out of litigation funding arrangements, which have never

been a basis for staying proceedings, even when litigation funding

was illegal[9].In the further circumstances that:

the ACCC has not commenced or even foreshadowed enforcement or

investigatory action, despite numerous notifications by the

Applicant, the ACCC's ongoing enquiries into the application of

Part IV to the Respondents and the establishment of a prima

facie case in these proceedings; andtraditional litigation funding firms have been unwilling to fund

the proceedings, despite it having a very high value book build

(MAW - 2 pg 453) and the establishment of a prima facie case,

the current proceedings are the only viable mechanism to enforce Part

IV against the Respondents and the only viable method for group

members to pursue their damages claims against the Respondents.

The blocking of the only viable mechanism to enforce Part IV and for

group members to obtain damages against the Respondents would

fundamentally undermine the principles of equality before the law

and access to justice. The public would rightly conclude that the

Respondents were above the law.In the further circumstances that the Respondents:

are among the most powerful and wealthy companies in the world;

control crucial channels of communications and information flows

relied upon by the public, businesses and governments alike;have exercised their power to influence political, legislative

and regulatory processes in their favour, de-platform entire

industries and become the arbiters of acceptable speech,

the blocking of the only viable mechanism to enforce Part IV and for

group members to obtain damages against the Respondents would

undermine public confidence in the justice system and bring it into

disrepute.

The Applicant's substantive claims rely on the Respondents' own

public documents (which the First Respondent has already admitted

the authenticity of) and reveal a case of very substantial merits,

the legal and factual basis of which has already been set out in

detail in ConSub. This is a further factor against a stay or

declassing of proceedings.To the extent that the Court considers that the concerns raised by

the Respondents have any validity, they can be easily managed and

mitigated by the Court's extensive powers, including under Part IVA

of the FCAA, to manage proceedings, practitioners, costs and approve

settlements.If the Court considers that the Respondents concerns justify

exceptional measures, it is bound exercise its power under s 43 (1)

of the FCAA to order the Respondents to provide funding to allow the

Applicant to retain a top-tier law firm and senior counsel to

prosecute proceedings (as the Supreme Court of Canada has done)[10]

rather than stay proceedings.In light of the above, the Respondents attempts to prevent the

substantive hearing of the Applicant[']{dir="rtl"}s Part IV claims

via interlocutory applications (including this application and the

foreshadowed strike out application) threatens to bring the system

of justice into disrepute and are clearly not in the interests of

the efficient administration of justice.The Applicant seeks that:

the Respondents interlocutory applications be dismissed;

the Applicant be awarded his out of pocket costs of this

application, such costs to be immediately taxed[11].

Conflict of Interest Generally

The Respondents allege that the current litigation funding

arrangements involve conflicts of interest.The Applicant submits that:

all litigation funding arrangements and indeed all litigation

involving legal representation involves potential and actual

conflicts of interest;any conflicts of interest involved in the current arrangements

are both quantitively fewer and qualitatively less problematic

than both those approved by the High Court in Fostif and

regularly occurring in typical funded class actions.the Court has the necessary tools to manage and mitigate any

conflicts of interest, if and when they arise, as proceedings

progresses.

The starting point for examining conflicts of interest is to to

determine:who are the relevant parties to an arrangement between whom

conflict of interest could exist;what is the source of potential conflict, in particular how do

the interests of the parties potentially pull in opposite

directions.

In the simplest form of (non-representative) litigation, an

applicant appears for themselves and there is no conflict of of

interest because there is only one person involved on the

prosecuting side.The introduction of legal representation adds one (solicitor) and

usually two (solicitor and barrister) additional parties prosecuting

the action and with it potential conflicts of interest.Solicitors and barristers have duties both to their client and to

the Court, as well as their own financial incentives. Solicitors may

be remunerated on a time based fee, fixed fee or success fee (25%

uplift of regular fees upon success) while barristers are

remunerated on a time based fee basis.All of this creates substantial potential and actual conflicts of

interest, including the following.Where all fees are time based, the client's interests are to

minimise legal costs, while succeeding in the action (more

efficient, success focus), while the solicitor and barrister

interests are to maximise billable hours while, remaining less

concerned about success (less efficient, success neutral).Where solicitors have a success fee arrangement, their interests

in success become more aligned with the client, but the interest

in maximising billable hours still remains opposite to the

client's interests (less efficient, success focus).Barristers and solicitors also have different financial

interests in litigation because the majority of solicitor work

is done in the earlier stages of litigation (front loaded)

while the majority of barrister work is done in the later

stages, particularly in appearance work at contested hearings

(back loaded). Thus barrister's financial interests are in

litigation proceeding to trial while the solicitors have a

greater interest in early settlement. Barristers also gain

experience and reputational benefits from actual Court

appearances, particularly in contested trials.

These conflicts of interest are managed by solicitor and barrister

rules, costs assessment procedures, the active management of the

Court, and to some extent, competitive, marketplace pressures.A typical externally funded class action (ie a shareholder class

action) introduces two or three additional party types into this

(already conflicted) arrangement:the litigation funder;

the group members who have signed the litigation funding

agreement (and agreed to the deduction of legal costs and the

funder's commission from their damages) ("funded group

members"); andunfunded group members (who absent Court intervention have no

deductions from their damages).

In the Australian Securities and Investment Commission Litigation

schemes and proof of debt schemes: Managing conflicts of interest

Regulatory Guide 248, ("ASIC Guide") states, at

RG. 248.11, that:

["]{dir="rtl"}The nature of the arrangements between the parties

involved in a litigation scheme or a proof of debt scheme has the

potential to lead to a divergence between the interests of the members

and the interests of the funder and lawyers because:(a) the funder has an interest in minimising the legal and

administrative costs associated with the scheme and maximising their

return;(b) lawyers have an interest in receiving fees and costs associated

with the provision of legal services; and(c) the members have an interest in minimising the legal and

administrative costs associated with the scheme, minimising the

remuneration paid to the funder and maximising the amounts recovered

from the defendant or insolvent company."

In addition, the unfunded group members have different interests to

the funded group members because (absent a common fund order or cost

sharing order) they obtain the benefit of success in proceedings

without paying the costs of obtaining it out of their damages award.Thus a typical funded class action has up to six separate groups who

have substantial potential and actual conflicts of interest.Furthermore, the interplay of financial incentives and reward is

both complex (because of numerous different remuneration bases) and

opaque to the group members (who generally do not have the capacity

to understand either the complex inter-relationships between funder,

solicitors and barristers or which legal costs are necessary and

efficient and which are not).These additional conflicts are managed by the ASIC Guide, funder's

conflict management policies, as well as Court practice notes and

active management by the Court.Despite all of the above conflicts of interest, the High Court, in

Fostif, authorised a wide range of litigation funding arrangements

under the broad public policy rubric: "[t]he law now looks

favourably on funding arrangements that offer access to justice so

long as any tendency to abuse of process is controlled"[12].And a wide variety of litigation funding arrangements are now a

regular part of the Australian litigation landscape[13].

Conflict of Interest in these Proceedings

These proceedings involve far fewer parties than a typical funded

class action and much less conflict of interest.Self representation by the legally experienced Applicant removes

solicitors and barristers conflicting financial interests from the

equation.The sole ownership of the litigation funder by the Applicant further

removes potential conflict between funder and the representative

Applicant. As the First Respondent has accepted, the interests of

the funder are entirely aligned with those of the applicant.[14]As a self represented applicant is unable to claim legal costs for

his/her time[15], and the litigation will only proceed if a No

Adverse Cost Order is granted[16], the issue of the legal costs of

prosecuting the claim and of adverse costs disappears. These costs

are the main driver of conflicts of interest in typical litigation

and funded class actions as outlined above.Far from creating a conflict of interest, the Applicant's interest

in the funder, JPB Liberty Pty Ltd, and in SUFB Tokens, serves to

better align the Applicant's interests with those of both the funded

group members and the group members as a whole.The interests of the Applicant and group members are fully aligned

from the reward perspective because:all parties obtain financial benefit only upon success;

rewards are calculated on the same basis, as straight

percentages of total damages without deductions (other than

disbursements) calculated on a different basis (ie legal costs

or management fees); andwhere the percentage shares are pre-agreed (in the litigation

funding agreement) and the 25% share allocated to Token Holders

is further allocated in advance of any final payout in a

transparent manner (displayed on the Hive blockchain in real

time) in proportion to the party's contribution to the success

of proceedings.

While the interests of the Applicant and group members are not

aligned from the risk perspective, this is no different from any

other class action where the Applicant and/ or funder takes the risk

of their own legal costs and adverse costs orders and group members

are not directly liable for any legal costs[17].The only conflict of interest which arises from non-aligned risk

between an applicant / funder and group members is the risk of an

applicant accepting a low settlement offer that does not properly

reflect the value of the group members's claims or otherwise seeking

to discontinue or abandon proceedings because an applicant / funder

may determine that risk outweighs potential reward.This issue is partly dealt with by the requirement for Court

approval of settlements and discontinuance and also, in these

proceedings, by ensuring that the Applicant / funders' potential

reward is high enough to justify the risk.The Applicant's cryptocurrency holdings were relatively small (under

A$10,000) in the early 2018 period for which the majority of market

based causation damages are claimed (see [9] and Annex C of Andrew

Hamilton 10 December 2020 Affidavit).As can be seen from the tables listing funded group members produced

by the Applicant (MAW - 2 pages 196 -211), many of the funded group

members had substantially larger cryptocurrency holdings than the

Applicant in this period. A number can be seen to have holdings in

the US$1 - 10 million range.The total claim of the funded group members exceeds A$1 billion

(see MAW -2 page 453 - 456) while the total claim of the many

millions of group members is approximately US$400 billion (see

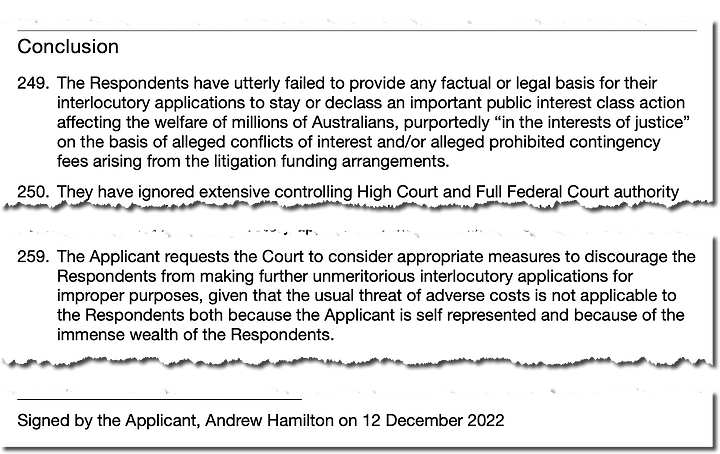

MAW-2 pages 232, 238, 326, 347, 453-456) which is over A$500

billion. Thus funded group members represent approximately 1/ 500th

of the total claim[18].Another method of coming to a similar conclusion is to compare

approximately 650[19] funded group members to the tens or hundreds

of millions of total group members[20].The Litigation Funding Agreement (clauses 10.1 and 10.2) provides

for 25% of the Litigation Proceeds (of funded group members) to be

paid to Token Holders and 5% to JPB Liberty Pty Ltd.The Applicant owns 100% of JPB Liberty Pty Ltd and a 48% effective

interest in the SUFB Tokens (see [3] of Andrew Hamilton 23 October

2022 affidavit) leading to a ~17% total interest in the claims of

the funded group members. This is an approximately 0.034% interest

(17% / 500) in the total claim of all group members.If the Applicant's financial interests in the proceedings were

limited to his own personal damages claim, there would a gross

imbalance between the potential returns to the Applicant from

success and the potential returns to many individual group members

and the group members as a whole.The Applicant would be carrying all the risk, expending all the

time, while having little upside to incentivise the continued

prosecution of proceedings. This would create conflict of interest

risks to the abandonment, discontinuance or settlement of

proceedings for a low sum that would not properly reflect the value

of group members claims.The effect of the Applicant's interests in the funder and SUFB

Tokens is to shift the Applicant from having a very small relative

financial interest in the potential proceeds, to having sufficient

interest to match some of the larger cryptocurrency holders, while

still being a very small percentage of the overall claim of group

members.This addresses the potential conflict of interest between the

Applicant and group members from the risk perspective.It provides an appropriate balance between risk and reward while

providing the lowest possible cost method of group members

prosecuting their claims.Traditional litigation funding arrangements would deduct substantial

legal fees from litigation proceeds prior to the percentage split,

whereas the current self representation arrangements mean funded

group members pay no legal fees out of their damages award.Compared to the complex and opaque interplay of financial incentives

in a typical funded class action (as outlined above), the

arrangements in these proceedings are far simpler, more transparent,

fairer and more easily understood by group members.The current arrangements eliminate the reward side conflicts of

interest in typical funded class actions and substantially mitigate

the risk side conflict of interest, inherent in all class actions.

They also eliminate the concern of proceedings being controlled by a

third party (the litigation funder) who is not before the Court.The interests of the applicant, litigation funder and group members

are entirely aligned from the reward perspective and as closely

aligned as possible from the risk perspective.The current arrangements are far superior to typical funded

litigation arrangements, particularly from the perspective of the

group members.

Benefits of Legally Experienced Self Representation

Self representation by a legally experienced applicant brings

substantial benefits to group members because it is far more

efficient and can deliver superior results in the right

circumstances.There are large inherent inefficiencies in the traditional client -

solicitor - barrister model of conducting litigation.The client, who has the greatest factual understanding of the case,

needs to spend extensive time (and money) explaining a myriad of

factual matters and commercial interests to the solicitors.The solicitors then spend a great deal of time and money converting

that information into a legally usable form (pleadings, evidence

etc).The solicitors then need to brief counsel and explain all the

relevant facts and legal bases all over again to counsel, who will

then conduct their own analysis of fact and law and prepare

submissions to the Court. Often there is an addition layer of junior

as well as senior counsel.This involves a huge amount of triple (or even quadruple) handling,

which is one of the reasons litigation in Australia is so expensive.With every communication and information exchange there is the

opportunity for mistakes and oversights and expenditure of time and

the client's money. There are an array of competing interests that

complicate things (as outlined at [23 -26] above). The process can

make it quite time consuming to do seemingly simple tasks.While it is rare for a self represented applicant to have the

necessary mix of skills and experience to both prepare proceedings

and act as an advocate in Court such a situation is ideal for group

members because it dramatically reduces costs and increases

efficiency.

Respondents alleged conflicts of interest

- In Fostif at [93] the High Court stated:

"As for fears that "the funder's intervention will be inimical to

the due administration of justice"[ ], whether because "[t]he

greater the share of the spoils ... the greater the temptation to

stray from the path of rectitude"[ ] or for some other reason, it is

necessary first to identify what exactly is feared. In particular,

what exactly is the corruption of the processes of the Court that is

feared?"[21]

The Respondents consistently speak of "intractable", "obvious" and

"hopeless" conflicts of interest yet fail to properly conduct the

basic first-principles analysis required to identify any real

conflict of interest (see [22] above).The First Respondent sets out its alleged conflicts of interest at

[33], [42], [45] and [46] of its submissions. I will examine

each in turn.Subparagraph 33(a) alleges, without evidentiary basis, that the

Applicant and JPB Liberty have an interest in minimising costs

incurred in conducting proceedings whereas the funded group members

would have an interest in the lead applicant incurring all costs

necessary to give the greatest prospect of success. The example of

expert evidence is given.This does not demonstrate even a potential conflict of interest:

the Applicant has as much interest as any funded group member in

ensuring the success of proceedings so has no interest in

minimising costs to the point it would compromise the success of

proceedings;the funded group members do in fact have to pay (out of their

damages) for all costs incurred in conducting successful

proceedings, so it is difficult to see why they would want to

increase these costs beyond what was strictly necessary to

facilitate the successful prosecution of proceedings.

The interests of the Applicant, funder and group members are

substantially aligned, not in conflict.The proposition also proceeds on a number of faulty assumptions:

while incurring certain costs may be essential to provide

reasonable prospects of success, spending more money does not

necessarily increase prospects of success;the Applicant's core cartel claim does not require economic

expert evidence (often required in Part IV claims) as there is

no requirement to establish a market or a substantial lessening

of competition;the Applicant has already demonstrated the capability to prepare

economic and market causation based evidence without relying

upon experts;the Applicant may be able to obtain economic expert evidence

without paying any or large amounts of money for it;there does not appear to be any controversy between the parties

in relation to other areas where potential expert evidence might

be required (eg cryptocurrency), in any case the Applicant

himself is an expert in this area and is able to cite a wide

range of external evidence to support his positions;if despite all of the above, it becomes apparent to the

Applicant that it is necessary to obtain expert evidence or

otherwise incur costs in order to not impair the Applicant's

prospects of success, then such costs can be paid for out of

existing JPB Liberty funds, sales of additional SUFB Tokens to

raise additional funds or by seeking Court orders that the

Respondents pay the costs of both set of experts or the

appointment of a joint expert.

Subparagraph 33(b) suggests that it may be in JPB Liberty's interest

to settle for a reduced sum while it may be in the interests of

group members to continue proceedings to seek a higher sum. Such

potential conflict is resolved by the requirement that the Court

approve settlements and by paragraph 3.17 of the Conflicts Policy

which ensures all settlement offers are communicated to group

members and they have the opportunity to require independent legal

advice on whether to accept a settlement.Subparagraph 33(c) makes the entirely nonsensical suggestion that

JPB Liberty, controlled by the Applicant, would seek to cease

funding proceedings and that this would somehow expose group members

to adverse costs orders. This does not make sense at all because:JPB Liberty would not act against the interests of the Applicant

who controls it by ceasing to fund proceedings - if the

Applicant / JPB Liberty wanted to cease proceedings the

Applicant would need to apply to discontinue proceedings, which

is subject to Court approval;group members would not be exposed to adverse costs orders even

if this did occur because of FCAA ss 33Q-33R and because

proceedings will only continue if a No Adverse Costs Order is

granted;the funding requirements on JPB Liberty while the Applicant

remains self-represented are relatively small and JPB Liberty

has no activity other than supporting these proceedings, so the

risk of JPB Liberty having to cease funding to preserve solvency

is negligible.

Paragraph 42 suggests that it may be in the interests of the

Applicant to crystallise his interest by settling proceedings at an

early stage when a smaller number of SUFB Tokens have been issued,

giving him a higher pro-rate share.What this suggestion ignores is that early settlement is generally

for a smaller sum (as noted by the First Respondent at [33(b)])

while later settlement may well be for a much larger sum. Thus the

hypothesised increase in SUFB Tokens on issue would be offset by the

large settlement sum.In light of the inherent uncertainties in litigation, damages

calculations, settlement offers, future funding and SUFB Token

issuance requirements, it is very difficult to draw the conclusion

that the First Respondent suggests, or indeed the opposite

conclusion. There is no conflict of interest because the actual

interests of both Applicant and group members on this issue cannot

be accurately determined and are not inherently in conflict.Settlement offers will need to be assessed at the time by the

Applicant, with the input from group members and external legal

advice as provided for by paragraph 3.17 of the Conflicts Policy and

if a decision is made to accept will then be subject to Court

approval. There is no conflict of interest and the interests of

group members are well protected.Subparagraph 45 suggests that the Applicant has an interest in

earning SUFB Tokens as cheaply as possible whereas it is in the

interests of the group members that any renumeration by way of SUFB

Tokens be structured so as to provide incentives for "very

significant" contribution to the prosecution of their claim. But

this is precisely the structure achieved by the litigation funding

arrangements - SUFB Tokens will be worthless unless the

self-represented Applicant does "very significant" work to ensure

the success of proceedings. It would be utterly pointless for the

Applicant to accumulate SUFB Tokens but not do the work to ensure

the group members damages claims are vindicated and thus the SUFB

Tokens become valuable. This is an alignment of interests, not a

conflict of interest.Subparagraph 46 suggests that the Applicant has an interest in JPB

Liberty issuing a minimum number of additional SUFB Tokens while the

group members have an interest in JPB Liberty issuing the full 18

million tokens to build the maximum "war chest": neither of those

assumptions is correct.The real interest of the Applicant, JPB Liberty and the group

members is to match fundraising via sale of SUFB Tokens on an

ongoing basis to the actual financial needs of the proceedings to

ensure they are successful. The idea that JPB Liberty should issue

all 18 million SUFB Tokens at some relatively early point to build

up a maximum war chest fails to understand the basic laws of supply

and demand and how startup businesses must fundraise.Firstly, there is currently insufficient demand for SUFB Tokens

for JPB Liberty to sell 18 million of them to build up a maximum

war chest;Secondly, demand for the SUFB Token will likely increase as the

proceedings move forward. As the Applicant gets "runs on the

board" and outside observers both become aware of the case and

consider the prospects of success more likely, demand for and

the price of SUFB Tokens will increase;Thirdly, the actual funding requirements to prosecute

proceedings effectively and efficiently are unknown at this time

and will only become apparent as the proceedings progress;The above three considerations mean that it is in the interests

of the Applicant, JPB Liberty and the group members to fund

raise progressively on an as-needs basis to take advantage of

increases in demand and thus price of SUFB Tokens and greater

clarity on actual funding needs as time progresses while always

retaining a substantial amount of SUFB Tokens and liquid assets

in reserve for contingencies.Fourthly, the classic litigation funding approach of raising a

large war chest in the early stages leads to self-fulfilling

over estimation of costs which is not in the interests of group

members (who ultimately must pay those costs plus a reasonable

ROI for the litigation funder).[22]

The First Respondent makes a number of arguments at [35] - [40]

identifying two circumstances where it says that the interests of

group members are unprotected because JPB Liberty's interests are

fully aligned with the Applicant' interests:in the event of JPB Liberty considering ceasing funding of

proceedings at [35 - 36];upon settlement or potential settlement of proceedings at [37 -

39].

The idea that JPB Liberty, fully controlled by the Applicant, would

cease to fund the proceedings in a way that would leave the

Applicant, but none of the group members liable to pay the costs of

proceedings, is ludicrous. Companies are controlled by their

directors and shareholders and the Applicant would never have any

reason to cause his own company to act against himself.In any case the interests of the group members are not affected by

such an entirely hypothetical decision by JPB Liberty to cease to

fund proceedings. It is only if the Applicant was to seek to

discontinue proceedings that the interests of the group members

would be affected. As discontinuance is subject to Court approval,

the interests of the group members would be protected.The issue that the First Respondent raises regarding clauses 11.6 to

11.8 of the LFA providing a conflict resolution method regarding

settlements that is only triggered if the Applicant and JPB Liberty

disagree is resolved by section 3.17 of the Conflicts Policy, which

provides an alternative mechanism to resolve such conflict.Section 3.17 ensures both that group members will have visibility of

all settlement offers and that there is a mechanism for group

members to force the Applicant & JPB Liberty to take independent

legal advice on a settlement offer. This protects the interests of

the group members and eliminates the concern raised by the

Respondents.In any case both the LFA and the Conflicts Policy can be amended to

address any deficiencies which the Court may identify.The Second Respondent sets out its alleged conflicts of interest at

[52] of its submissions. I will examine each in turn.Subparagraph 52(a) merely identifies that the Applicant benefits

from a share of the funded group members damages in addition to his

own. But both the group members and the Applicant only obtain this

benefit if proceedings are successful and damages payable and both

obtain nothing if proceedings are unsuccessful. This is an alignment

of interests, not a conflict of interest.Subparagraph 52(b) suggests that the Applicant has in interest in

earning SUFB Tokens as cheaply as possible whereas it is in the

interests of the group members that any renumeration by way of SUFB

Tokens be structured so as to incentives real meaningful

contribution to the prosecution of their claim. But this is

precisely the structure achieved by the litigation funding

arrangements - SUFB Tokens will be worthless unless the

self-represented Applicant does real, meaningful work to ensure the

success of proceedings. It would be utterly pointless for the

Applicant to accumulate SUFB Tokens but not do the work to ensure

that the group members damages claims are vindicated and thus the

SUFB Tokens become valuable. This is an alignment of interests, not

a conflict of interest.Subparagraph 52(c) merely identifies the different risk profiles

between a representative applicant and group members that is

inherent in all representative proceedings. This issue is examined

at [43 - 56] above. The litigation funding arrangements in these

proceedings substantially mitigate this potential conflict of

interest.Subparagraph 52 (d) alleges, without evidentiary basis, that the

Applicant and JPB Liberty have an interest in minimising out of

pocket expenses and that, somehow, creates a conflict of interest,

presumably with group members. The actual mechanism for this alleged

conflict of interest is not identified. There is no evidence that

group members have an interest in maximising out of pocket

expenses, such as would be required for there to be a conflict with

this alleged interest. Indeed it is unclear why group members would

wish to increase costs which they ultimately must pay out of their

damages award if the case is successful. The Second Respondent seems

to have an unstated assumption that more money equals a better

result. This is a false assumption.However the real interest of the Applicant, JPB Liberty and the

group members is to match fundraising via sale of SUFB Tokens to the

actual financial needs of the proceedings to ensure that they are

successful. Self representation by the Applicant frees up funds

raised from sales of SUFB Tokens to allow them to be spent on

necessary external expenses, as and when required, rather than on

legal fees.Traditional litigation funders build up a large "war chest",

sufficient to cover all anticipated needs (including their own

costs, adverse costs orders and security for costs) plus

contingency, prior to commencing proceedings. They then need to

ensure that money is spent and an appropriate return on investment

(ROI) is achieved on this large investment. However this is not the

only way to fund litigation, nor is it necessarily in the interests

of group members. A large war chest and the ROI required by it

necessarily comes out of the group members' pockets, usually by way

of legal costs and disbursements. The knowledge of a large war chest

encourages law firms to do more work and charge more money, but does

not necessarily lead to better litigation outcomes.JPB Liberty has created a structure where SUFB Tokens can be sold on

an ongoing basis as proceedings continues to fund out of pocket

expenses as and when they become necessary. In particular, the

Applicant's cartel claim proceeds on the basis of the Respondent's

public documents (now admitted as authentic by the First Respondent)

and will likely not require any expert evidence to prove liability.Thus the Respondents have failed to identify a single real conflict

of interest arising out of the litigation funding arrangements in

these proceedings.

Legal Basis for Staying Proceedings

The High Court has consistently held the power to stay otherwise

lawful proceedings, preventing them from continuing to a hearing on

the merits is one to be exercised only in "the most exceptional

circumstances"[23] and is a "highly unusual" step[24] to be

exercised with "great care" and "extreme caution"[25].Kirby J in Fostif at [142 - 145] examines this issue in detail,

both in the context of representative proceedings and generally and

states the following:

"it is important to recognise how exceptional it is for a court to

bring otherwise lawful proceedings to a stop, as effectively the

primary judge did in this case. It is very unusual to do so by

ordering the permanent stay of such proceedings""The reason why it is difficult to secure relief of such a kind is

explained by a mixture of historical factors concerning the role of

the courts; constitutional considerations concerning the duty of

courts to decide the cases people bring to them; and reasons grounded

in what we would now recognise as the fundamental human right to have

equal access to independent courts and tribunals[]. These

institutions should be enabled to uphold legal rights without undue

impediment and without rejecting those who make such access a reality

where otherwise it would be a mere pipe dream or purely theoretical."

The correct law on whether there is an abuse of process which may

justify a stay of proceedings in the context of litigation funding

agreements is: "whether proceedings funded by a litigation funder

are an abuse of process depends on whether the role of that funder

'has corrupted or is likely to corrupt the process of the court to a

degree that attracts the extraordinary jurisdiction to dismiss or

stay permanently for abuse of process'"[26].The "corruption of the processes of the Court" is identified as

"the champertous maintainer might be tempted, for his own person

gain, to inflame the damages, to suppress evidence, or even suborn

witnesses."[27]It is most certainly not mere conflict of interests, which "are an

inevitable by-product of a regime where the self appointed

representative applicant's individual claim is the vehicle through

which the common questions are to be tried."[28] As demonstrated

above, the conflicts of interest in these proceedings are far less

than in typical funded class actions.Gaudron J in Jago also examines the nature of the power to grant a

permanent stay.

"The nature of the power to grant a permanent stay of proceedings

itself reveals an important principle which confines its exercise. The

power is, in essence, a power to refuse to exercise jurisdiction. It

is thus to be exercised in the light of the principle that the

conferral of jurisdiction imports a prima facie right in the person

invoking that jurisdiction to have it exercised. In this context it is

relevant to note the remarks of Deane J. in Re Queensland Electricity

Commission; Ex parte Electrical Trades Union of Australia [1987] HCA

27; (1987) 61 ALJR 393, at p 399; 72 ALR 1, at p 12, that the "prima

facie right to insist upon the exercise of jurisdiction is a

concomitant of a basic element of the rule of law, namely, that every

person and organisation, regardless of rank, condition or official

standing, is 'amenable to the jurisdiction' of the courts and other

public tribunals". Thus, the power is one that is readily seen as

exercisable (whether in civil or criminal proceedings) only in

exceptional cases or, as was said by this Court in refusing special

leave to appeal in Attorney-General (NSW) v. Watson (1987) 20 Leg Rep

SL 1, "sparingly, and with the utmost caution". See, generally,

Cocker v. Tempest [1841] EngR 242; (1841) 7 M & W 502 (151 ER 864);

Lawrance v. Norreys, at p 219; Humphrys, at p 26; and Reg. v. Derby

Crown Court; Ex parte Brooks (1984) 80 Cr App R 164, at p 168."[29]

The already very high bar to ordering a permanent stay established

by the above High Court authority, rises even higher when, as in

these proceedings, the Court has already determined that the

Applicant has a prima facie case and that there is public interest

and has actively exercised its discretion to exercise

jurisdiction.[30]This issue was examined in detail in Williams v Spautz[31] where

the High Court held that where a litigant has a prima facie case,

a predominant improper purpose in bringing and maintaining proceeds

is not enough to justify a stay. It must also be shown that the

litigant does not intend to pursue the cause of action to a

conclusion.[32]In light of the above there is a real question as to whether this

Court is effectively estopped by its previous decision in Hamilton

to exercise jurisdiction (on a prima facie case and public

interest basis) from subsequently refusing to exercise jurisdiction

"in the interests of justice", unless it was convinced that a prima

facie case and public interest no longer existed.The Respondents have cited no authority supporting the proposition

that mere conflicts of interest arising from litigation funding

arrangements rises anywhere near the level of predominant improper

purpose or is in any way exceptional, especially when as outlined in

detail above, conflicts of interest are common place in funded class

actions.Moreover, even prior to the Maintenance, Champerty and Barratry

Abolition Act 1993 (NSW), when litigation funding arrangements were

considered unlawful maintenance and champerty or trafficking in

litigation, such concerns were not a ground for staying

proceedings.[33]It is also notable that the arrangements in the current proceedings

would not have infringed those now abolished prohibitions because

both JPB Liberty Pty Ltd and all the Token Holders are group members

in the proceedings (by virtue inter alia of their holdings of

Listed Cryptocurrencies) and thus have an interest in the subject

matter of proceedings independent from their right to share in the

litigation proceeds deriving from the LFA.[34]

Footnotes / Endnotes

Campbells Cash and Carry Pty Limited v Fostif Pty Limited

[2006] HCA 41 (Fostif) at [83] - [95] per Gummow, Hayne

and Crennan JJ; Gleeson CJ agreeing at [1] ("Fostif

majority"). ↩Voth v Manildra Flour Mills Pty Ltd [1990] HCA 55; 171 CLR 538

(Voth) at [30]. ↩ibid ↩

See Meta submissions at [4] and Google submissions at [3]. ↩

Parkin v Boral Ltd (Class Closure) [2022] FCAFC (Parkin)

at [126] per Murphy and Lee JJ, Beach J agreeing at [156] ↩Perera v GetSwift Limited [2018] FCAFC 202 (Perera) at

[60]. ↩Hamilton v Meta Platforms, Inc (Service out of Jurisdiction)

[2022] FCA 681 (Hamilton) at [40] ↩Epic Games, Inc v Apple [2021] FCAFC 122 (Epic) ↩

Fostif at [81 - 82] per Fostif Majority. ↩

British Columbia (Minister of Forests) v Okanagan Indian Band

[2003] 3 SCR 371, 398 [38](LeBel J for McLachlin CJ, Gonthier, Binnie, Arbour, LeBel and

Deschamps JJ) (Okanagan) at 400 [41]. ↩See Spotwire Pty Ltd v Visa International Service Association

(No 2) [2004] FCA 571 at [104]. The Respondents' misuse of the

Court's processes to avoid substantial hearing should be

discouraged. The proceedings are likely to continue for years.The

Respondents were given early and clear notice of the fundamental

defects in their interlocutory applications before they were filed

(failure to identify and particularise conflict of interest,

reliance on clearly weak, wrong and inapplicable cases). ↩Fostif at [65] per Fostif Majority and Kirby J at [135 -

136] [142- 145] ↩See Integrity, Fairness and Efficiency - An Inquiry into Class

Action Proceedings and Third-Party Litigation Funders [2018] ALRC

134 ("ALRC 134") at [2.11 - 2.16]. ↩Meta submissions at [32]. ↩

Bell Lawyers Pty Ltd v Pentelow [2019] HCA 29. ↩

[5] of Applicant's Interlocutory Application dated 27 August

other than costs incurred solely in relation to a group member's

individual claim. See FCAA ss 33Q-33R, 43(1A). ↩The Applicant has explained the basis for these claim value

calculations at [141 - 157] of the Applicants Consolidated

Submissions dated 13 July 2021 with links to relevant filed

affidavit material all of which was served on the Respondents in

August 2022. In any case it is the relativity between the value of

claims of funded group members to total group members that is

relevant for these purposes, not absolute numbers. ↩"over 650" as per [38] of 27 August 2020 affidavit of Andrew

Hamilton and verifiable by counting the lines in the tables listing

funded group members produced by the Applicant (MAW - 2 pages 196

-211). ↩See [9 - 10] and Annex B of Andrew Hamilton 23 October 2022

Affidavit. ↩per Fostif Majority. ↩

See more detailed discussion on this point at [98] below. ↩

Jago v District Court of NSW [1989] HCA 46; (1989) 168 CLR 23

(Jago) at pg 34 per Mason CJ at [14] ↩Fostif per Kirby J at [143]. ↩

Voth at [30]. ↩

Fostif at [63] per Fostif Majority. ↩

id. at [93] ↩

Parkin at [126]. ↩

Jago per Gaudron J at [14], Brennan J at [13] making the

same point. ↩Hamilton at [36 - 41]. ↩

Williams v Spautz [1992] HCA 34; (1992) 174 CLR 509

(Spautz) at [23 - 24] per Mason CJ., Dawson, Toohey and

McHugh JJ. ↩Note also the statement of Toohey J in Jago at [29] that it

is only in cases of improper purpose that no remedy other than a

stay is appropriate. ↩Fostif at [81 - 82] per Fostif Majority. ↩

Fostif at footnote 58 and [73] per Fostif Majority. ↩

Your work on this has been epic. Seriously. In less than 7 days you produced a blockbuster reply to two of the biggest law firms in Australia (which are actually both international firms as well).

Not only that, the full response (which I thoroughly recommend anyone to read) is a work of art and it was actually fun at times to read through drafts of this as it was written.

If you don't look at anything else, look at the conclusion:

Epic work! Respect!