India's certainly has the potential to be a major geopolitical power. It's economy - already one of the largest in the world, will continue to grow if it does not engage in large scale conflict with its neighbours.

Potentials

India's political priorities for the next few decades will likely continue to be based on domestic priorities, such as eradicating poverty and improving public health. There are still significant geopolitical, geoeconomic and diplomatic roles that India can play.

India's position in the Indian Ocean provides tremendous geopolitical and security influence. To the east is Southeast Asia, and the Pacific Ocean; to the West is Africa, the Middle East, and beyond that, Europe. A strong India could easily contribute to security issues in both directions.

An India that is rapidly developing could likewise become an economic engine for the whole world, as was China. An India that has well-developed capital markets and a pro-business environment could attract global companies for its large market and workforce. Even Chinese companies in pursuit of global growth might have to come to India to access its market. A thriving India can also become a consumption market for Africa - especially Eastern Africa.

India can also play an important role in global diplomacy as a voice for developing countries that still need the space to develop. Having India involved in issues of global development will mean considerable weight.

Fulfilling the Potentials

Beyond these potentials, India's governing elite would have much to do to realise them. The issues are deep-seated, and will require several generations of concerted fashion, not unlike America's reckoning with racism. These issues as one might guess, has to do with gender discrimination and with the caste system. The economic reasoning should be clear enough - for one gender to be discriminated against in everyday life, in socio-cultural terms, and in economic terms would already be a major self-inflicted wound in terms of economic potential. The caste system, even in informal terms unnecessarily reduces human potential and can become an impediment in the project of economic mobility and poverty eradication. Simply writing off a large section of the population for economic potential would be itself, another self-inflicted wound in the journey of economic development.

Then there are other issues, such as the extent to which the government of India supports state-owned companies, with some parallels with China. Bad debts continue to accrue to some under-performing institutions, with the potential to undermine India's banking and financial sector. India's economic elite has to find a way to manage these bad debts and the poorly performing institutions and continue in the direction of liberalisation.

India's governing elites also has to continue to make progress in things such as basic sanitation and public health. Although there was a campaign to build public toilets to address the issue of open defecation, it still remains an issue. The society and culture must change too, for women and girls to obtain easy access to menstrual hygiene rather than keep them isolated from community and schooling. And these are just the basics. In addition to those, India's governance must also include a plan to raise the standard of primary and secondary education, and especially in rural communities, which still form a large part of India. Governance cannot just be for the urban communities where economic activity and wealth are concentrated; much parts of India are still rural and will need particular attention.

Energy and Climate Change

Other than the socio-cultural-economic issues, India has a second set of issues to contend with: energy and climate change. India is still reliant on coal for its energy mix - with more than half of primary energy used in India coming from coal. In an era of climate considerations, India will have less and less manoeuvring space to justify such a large proportion of energy usage through coal. India might already be a significant user user of solar and wind power, but even that would have to accelerate for those efforts to have a significant share of energy production.

Climate change also makes life difficult for rural India. Changing weather could make parts of India 'unliveable' while changing weather patterns might cause disruptions to food production - farmers not able to earn their income as crops fail; communities might become vulnerable to droughts or floods. India will also have to deal with the persistent issue of water scarcity. India's governing elite will again have to come up with a longer-term plan that will be able to address these issues in a comprehensive way.

Social Identities

The recent turn towards religion as a way to create a coherent sense of identity is troubling. Such an approach makes minority groups insecure and again, reduces social cohesion broadly, given how India still has a substantial Muslim minority. This question of Indian identity will continue to loom large in the years to come.

Will India remain an inclusive country that is able to create growth for the majority of the country, or will economic growth be limited to a tiny sliver of the urban elite? Will India be able to develop a broad pluralistic identity or could it double down on the narrow religious-nationalist identity? Will India's governing elite be able to address the longer-term challenges of climate change and liveability?

India's Geopolitical Positioning

India's historical geopolitical identity has that of an independent power that wants to decide on issues for itself. Will it continue to be stay that way, selectively bandwagoning with major powers out of convenience? How might it choose to use that influence? If indeed the US-China axis is going to be a geopolitical organising principle, how might India navigate these circumstances?

Then there is the question of it relations with Pakistan. Will India and Pakistan be able to come to some kind of modus vivendi that would eschew military conflicts? Could India and Pakistan ever go to large-scale war? Even a limited nuclear exchange between the two countries would create global climate change, lasting for years.

These are just thumbnail sketches for India. From the perspective of 2020, it seems difficult for India to embark on the kind of sustained take-off double-digit growth that China embarked on in its initial years of economic liberalisation. Neither does the current set of economic elites seem receptive to economic liberalisation. India's governing elites would have to address basic issues of public health, education, skills, and inclusiveness to create broad-based growth.

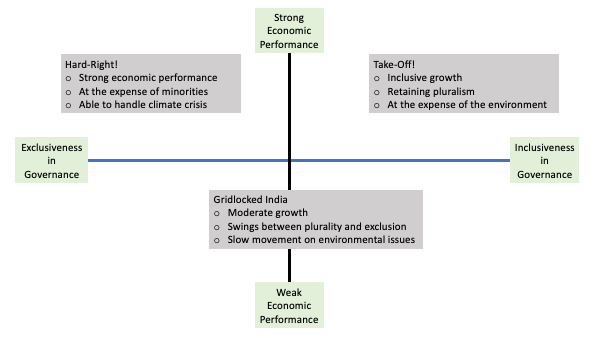

There are broadly these scenarios that for India's trajectories:

Take-Off India where elites are able to create inclusive growth and rapid development, though at the cost of a deteriorating environment;

Hard-Right India, where trends of autocratic rule take hold, at the expense of minorities;

Gridlocked India, where no political or economic guidelines take hold for a long time, and the country lurches between different economic and social prerogatives, and economic development continues at the 5–8% growth rate for the foreseeable future.

The world will not wait for India; political elites in India will have to decide what legacies they want to leave behind.