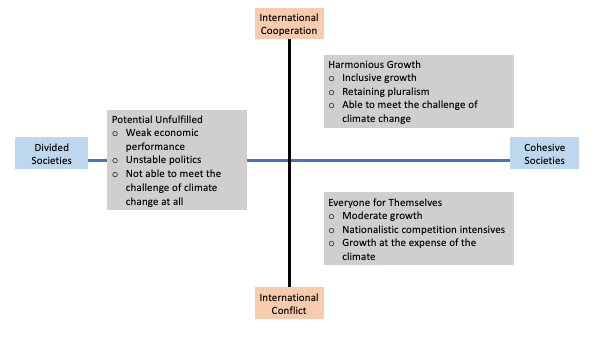

I see the main trends having to do with the capacity of states to be coherent and capable to handle the various other possible disruptions, and the extent they are able to cooperate with each other.

Southeast Asian states will be in a quandary. Multiple issues threaten the prosperity and welfare of Southeast Asian states as a whole. Geopolitical rivalries and state capacity, together with climate change, are issues that will threaten the coherence of Southeast Asian states, and economic prosperity.

The coherence of governance in all Southeast Asian countries will be the key — how they are able to develop economically, protect their populations against the impacts of climate change, and their ability to provide their people with the skills to participate meaningfully in the global economy and keeping up with technological disruptions.

Near-Term opportunities (next 5 years?)

Changes in the patterns of globalisation are afoot. Countries are adjusting supply chains to be closer to their consumption markets, and so will shift. Geopolitics is also becoming an increasing factor for companies to decide on where to have their production sites. Given that Southeast Asia’s relatively young population and rapid economic growth is likely to last for a few more decades, and given the ambivalent geopolitics of the region, there is a good case to make for Southeast Asia to be a major production site. While for now the region as whole might not be able to match the technical sophistication of the Chinese production chain, in a few more years, and with even more investments, Southeast Asia as a whole, and perhaps countries like Vietnam, the Philippines and especially Indonesia, together combined can match the levels of sophistication required for future production. But this is a big “IF” of course. It will require substantial social investments in the basic areas of life — good health and nutrition and good education that can cope with he demands of the modern world. These countries need to enforce good governance — keep corruption low and provide a stable business environment where courts are not prejudiced against foreign companies all the time. Having a strong legal system that is seen as fair will also go a long way towards settling disputes when they arise.

State Capacity

Over the longer-term, the dangerous things to watch for Southeast Asia would be the socio-political instability stemming from the intersections of inequalities and identities. The ethno-nationalist states of Southeast Asia would be particularly vulnerable to divergent pushes of identities, especially if these states comprise significant proportions of minorities. A push towards ethno-nationalism would be a dangerous one. For countries in Southeast Asia to remain on the path towards economic prosperity, society and governments must find ways to engage with their diversity and encourage inclusive growth for all, not just the majority.

Inter-state cooperation

Another factor that could determine the trajectory of Southeast Asia would be the extent to which they can cooperate with each other — whether they will have able to cooperate each other and build a framework to establish relations with the other great powers, or whether they end up following different blocs made up of the great powers and compete against each other intensely. Such a division would produce intra-regional conflicts and competing intensely against each other. Without being able to cooperate with each other, they would withhold resources from each other and reduce the level of growth the would otherwise maintain. A region that is able to cooperate well with each other can enjoy the full range of talent and resources with each other could easily create production and consumption value chains.

While Southeast Asia is likely not to be politically integrated in the manner of Europe given the divergent histories and the different levels of economic development, the integration that Southeast Asia follow will probably be geared towards economic integration — flows of people and goods and services and information. However, this can only be achieved if there is a common standard of cooperation.

On the other hand, a Southeast Asia divided along the lines of major power blocs can descend into military conflict in the extreme, as each power seeks to probe the strength of partnerships amongst their patrons. In such a zero-sum world, a gain by any country can easily be seen as a loss for the other, prompting needly escalations.

Identity as Cleavages

Other than this kind of division, Southeast Asia as a region could also become competitive along lines of identity. A Southeast Asia divided along religious or ethnic lines could see countries supporting or suppressing minority religious groups in their own countries, or use minority groups in other countries to undermine societies in other countries. For instance, policies deemed to be anti-Islam in one country could generate social protests in another country, spurring calls for intervention — humanitarian or otherwise. Discrimination of a minority group, but a majority in another, could also spur such similar responses. The diversity of Southeast Asia — of language, faith, and culture ought to be a strength — of how a diverse group of peoples can work together for prosperity and enriching each other. if this is not possible, the region can all too easily enter a period of protracted conflict, ending in even possibly genocide-like outcomes.

In such contexts, issues such as climate and technological disruptions are stressors that states must handle appropriately. These issues are catalysts or accelerants — they can enable societies to attain prosperity faster, or slower; they can amplify social cleavages or help to bring people together.

The role for companies

In Southeast Asia, corporates often have a social role as well, anchored in the cultural context of their societies. Corporates often portray themselves as being rooted in the community and reflecting the cultural values of the societies they come from. The idea of ‘stakeholder’ has much salience here. They can serve as important catalysts for change — bringing together producing communities and consumption communities together, especially for businesses that still engage in primary resource-related industries. Given how some corporates are closely associated with political elites in their own countries, this social angle is even more important for enterprise survival. Being associated with the ‘incorrect’ set of elites could easily lead to business disruption or even worse consequences. As a result, corporates will continue to be politically-sensitive and serve other social purposes. They have a role in spreading the required skills and knowledge for their employees and the communities they serve and increase the adaptability of their communities to the various disruptions that are coming.

Technological Disruption — A Tractable Challenge

Technological disruption — as scary as it is, it is still fundamentally a tractable challenge, but states must make the investments in human capital — in health, education and in the information infrastructure — so that the gains from technology can be distributed across a broad range of society. There is talent in Southeast Asia who are able to seize the opportunities afforded by the technologies and become at least a technology hub of some renown.

Climate Change

For Southeast Asia, climate change still holds the greatest threat. Climate change disrupts weather patterns, could affect agricultural output, increases the risks of flooding — altogether possibly causing massive economic losses, and destabilizes political cohesion throughout Southeast Asia. Climate change has the potential to disrupt crop yields and create food insecurity, spurring all kinds of other effects for which governments might be ill-prepared for. Climate change could create disruptive climate, creating direct economic losses. Events considered once-in-a-century could happen with greater frequency than expected. These effects could then have geopolitical consequences, such as when climate events force people to migrate to safer places, and forced to move across borders. Without a shared framework for cooperation for these kinds of events, these geopolitical crises could trigger other events that could precipitate further tragedies. In a geopolitically fractured context, this becomes even more dangerous, to the extent that countries could end up in skirmishes with each other. If ethno-nationalism becomes an organising and legitimising principle for states in the region, then the prospects of war increase, and with that, the prospects of economic growth will also diminish.

A Geopolitical Prisoners’ Dilemma

There are many things going for Southeast Asia, but there are also several things going against it. The region would have to find routes for cooperation even with their geopolitical or ethnic-nationalist differences, for a very challenging period to come. This would, however, come up against the geopolitical options that individual countries can have — in the absence of a shared framework for cooperation, every individual state may play the interests of different powers and neighbouring countries against each other, creating fragmented opportunities across the region — a geopolitical instance of the Prisoners’ Dilemma — while it is in the interest of every country to cooperate with each other and present a consistent front in the approach towards major powers, every individual country also has immense gains from defecting and seek their own bargains with major powers if it affords them gains, even at the expense of everything else. We can only hope that the experimental outcomes/simulations might also manifest in this real-life game — while “tit-for-tat” (cooperation for cooperation, defection for defection) was the winning strategy against other pro-defection strategies, more pro-cooperation strategies could create more global gains. Would Southeast Asian countries heed these findings?

Harmonious Growth — inclusive growth that embraces the diversity of the region and culture, and able to meet the challenge of climate change sufficiently;

Everyone for Themselves — moderate growth through intense nationalistic competition, without benefitting from possible cooperation. Climate considerations are ignored, thinking that these might shackle growth.

Potential Unfulfilled — fragmented societies lead to unstable politics and weak economic performance. Local communities fend for themselves as the effects of climate change manifest.

*This post is also here: https://medium.com/open-source-futures/trends-for-southeast-asia-c1b1b45ae17d

Consider a contribution to https://www.patreon.com/opensourcefutures if you enjoyed this!*