Hierapolis, whose name means "sacred city," was believed by the ancients to have been founded by the god Apollo. It was famed for its sacred hot springs, whose vapors were associated with Pluto, god of the underworld. The city also had a significant Jewish community and was mentioned by Paul in his Letter to Colossians.

Today, Hierapolis is a World Heritage Site and popular tourist destination. In addition to interesting Classical ruins, the site offers a thermal Sacred Pool in which you can swim with ancient artifacts, a view of the spectacular white terraces of Pamukkale, and a good museum.

In the Bible

Hierapolis is mentioned only once in the Bible, when St. Paul praises Epaphras, a Christian from Colossae, in his letter to the Colossians. Paul writes that Epaphras "has worked hard for you and for those in Laodicea and in Hierapolis" (Colossians 4:12-13). Epaphras was probably the founder of the Christian community at Hierapolis.

Ancient tradition also associates Hierapolis with a biblical figure, reporting that Philip died in Hierapolis around 80 AD. However, it is not clear which Philip is menat. It could be Philip the Apostle, one of the original 12 disciples, who is said to have been martyred by upside-down crucifixion (Acts of Philip) or by being hung upside down by his ankles from a tree.

Or Philip could be Philip the Evangelist, a later disciple who helped with administrative matters and had four virgin-prophetess daughters (Acts 6:1-7; 21:8-9). Early traditions say this Philip was buried in Hierapolis along with his virgin daughters, but confusingly call him "Philip the Apostle"! In any case, it seems a prominent person mentioned in Acts did die in Hierapolis.

History of Hierapolis (Pamukkale)

Usually said to be founded by Eumenes II, king of Pergamum (197-159 BC), Hierapolis may actually have been established closer to the 4th century BC by the Seleucid kings.

The name of the city may derive from Hiera, the wife of Telephus (son of Hercules and grandson of Zeus), the mythical founder of Pergamum. Or it may have been called the "sacred city" because of the temples located at the site. (The name Pamukkale is sometimes used just to refer to the white terraces, but the modern name of the whole area is also Pamukkale.)

With Colossae and Laodicea, Hierapolis became part of the tri-city area of the Lycus River valley. Hierapolis was located across the river from the other two cities and was noted for its textiles, especially wool. The city was also famous for its purple dye, made from the juice of the madder root.

The hot springs at Hierapolis (which still attract visitors today) were believed to have healing properties, and people came to the city to bathe in the rich mineral waters in order to cure various ailments.

Hierapolis was dedicated to Apollo Lairbenos, who was said to have founded the city. The Temple of Apollo that survives in ruins today dates from the 3rd century AD, but its foundations date from the Hellenistic period.

Also worshipped at Hierapolis was Pluto, god of the underworld, probably in relation to the hot gases released by the earth (see the Plutonium, below). The chief religious festival of ancient Hierapolis was the Letoia, in honor of the the goddess Leto, a Greek form of the Mother Goddess. The goddess was honoured with orgiastic rites.

Hierapolis was ceded to Rome in 133 BC along with the rest of the Pergamene kingdom, and became part of the Roman province of Asia. The city was destroyed by an earthquake in 60 AD but rebuilt, and it reached its peak in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD.

Famous natives of Hierapolis include the Stoic philosopher Epictetus (c.55-c.135 AD) and the philosopher and rhetorician Antipater. Emperor Septimus hired Antipater to tutor his sons Caracalla and Geta, who became emperors themselves.

Hierapolis had a significant Jewish population in ancient times, as evidence by numerous inscriptions on tombs and elsewhere in the city. Some of the Jews are named as members of the various craft guilds of the city. This was probably the basis for the Christian conversion of some residents of Hierapolis, recorded in Colossians 4:13.

In the 5th century, several churches as well as a large martyrium dedicated to St. Philip (see "In the Bible," below) were built in Hierapolis. The city fell into decline in the 6th century, and the site became partially submerged under water and deposits of travertine. It was finally abandoned in 1334 after an earthquake. Excavations began to uncover Hierapolis in the 19th century.

What to See at Hierapolis (Pamukkale)

What to See at Hierapolis (Pamukkale)

Long before you arrive in Hierapolis, you can see the gleaming white travertine terraces of Pamukkale, located next to the ruins of Hierapolis. The extraordinary effect is created when water from the hot springs loses carbon dioxide as it flows down the slopes, leaving deposits of limestone. The layers of white calcium carbonate, built up in steps on the plateau, gave the site the name Pamukkale ("cotton castle"). Unfortunately, but understandably, visitors are no longer allowed to walk on the terraces in order to protect them from damage.

A good place to start your tour is the small but excellent Pamukkale Museum, located near the parking area and housed in part of the south Roman baths (early 2nd century BC). The displays are presented attractively and include signs in Turkish and English. The collections include coins, jewelry, sarcophagi and architectural fragments among other items; the highlights are the statues and reliefs.

After the museum, there is a lot to see among the ruins of Hierapolis. Most of what you see today is from the Roman period, as the original Hellenistic city was destroyed by successive earthquakes in 17 AD and 60 AD. The site is surrounded by Byzantine walls, outside of which is an extensive necropolis.

Nearest the museum is a complex that includes the Sacred Pool, a colonnaded street, and a basilica church. The Sacred Pool is warmed by hot springs and littered with underwater fragments of ancient marble columns. Possibly associated with the Temple of Apollo, the pool provides today's visitors a rare opportunity to swim with antiquities! During the Roman period, columned porticoes surrounded the pool; earthquakes toppled them into the water where they lie today.

Behind the Sacred Pool is the nymphaeum, a monumental fountain that distributed water to the city. Dating from the 4th century AD, it has been partially restored. Three walls surround a basin of water, which was approached by steps on the open side. Statues filled the niches in the walls.

Next to the nymphaeum is the Temple of Apollo, the patron god and divine founder of the city. All that remains are the foundations, platform and entry steps; the foundations are Hellenistic and the rest is Roman (3rd century AD).

South of the temple is the Plutonium, a sacred cave believed to be an entrance to the underworld, the domain of the Roman god Pluto (the Greek Hades). The cave emitted poisonous vapors in ancient times, and still does! For this reason, the entrance is sealed off. According to the Greek geographer Strabo, the priests of Cybele were able to enter the sacred chamber safely, but animals who entered it died (Geography 13.4.14).

East of the Temple of Apollo, toward the theater, are the ruins of a peristyle house with Ionic columns. Dating from the 6th century AD, it includes a courtyard with a floor made from polished stone or glass (called the "opus sectile technique").

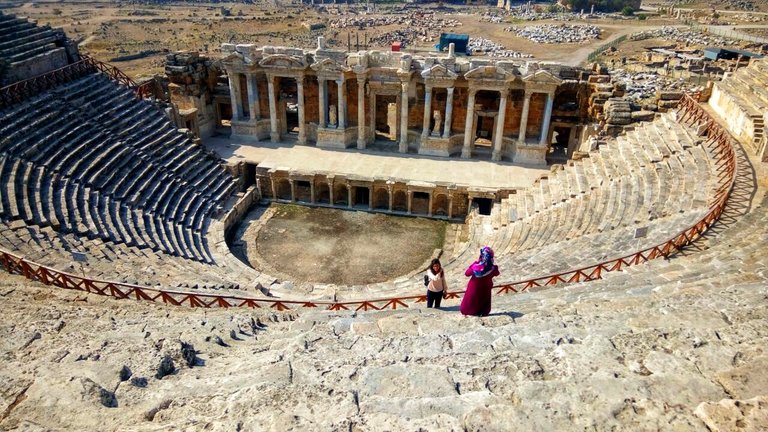

The theater of Hierapolis is well-preserved, especially the stage buildings, which were beautifully decorated with reliefs. Constructed around 200 BC, the theater could hold 20,000 spectators and had reserved seating for distinguished spectators in the front row. Today, just 30 rows of seating have survived.

The main thoroughfare of Hierapolis was a wide, colonnaded street called the Plateia, which ran from the Arch of Domitian to the south gate.

There is a ruined church across from the Martyrium near the Agora and another one built inside the baths on the other (north) side of the Agora.

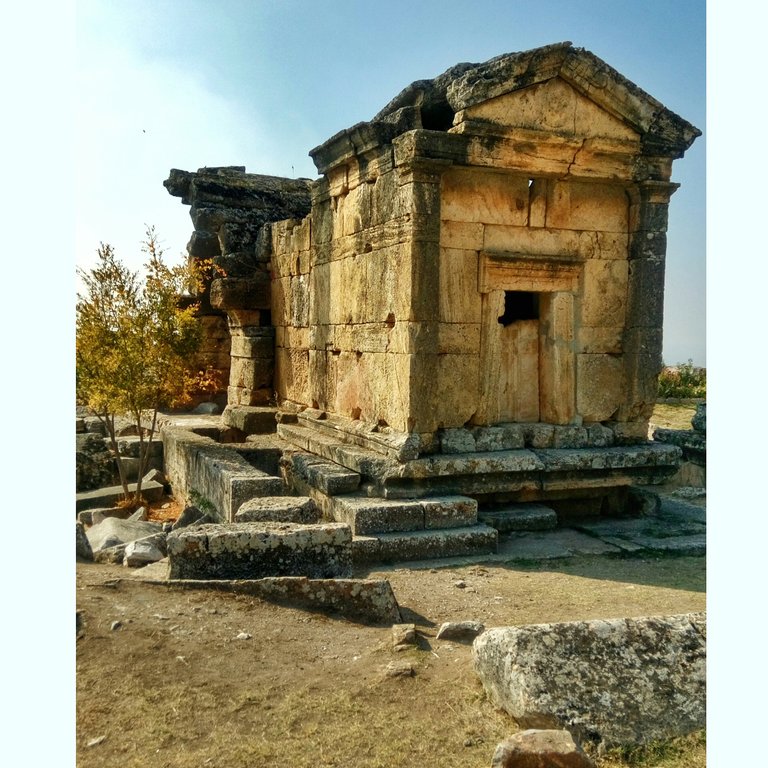

The Martyrium (or Martyrion) of St. Philip, outside the walls by the northern part of the city, was built in the 5th century AD on the site of Philip's martyrdom (see "In the Bible," above). A square building with an octagonal rotunda, it measures 65 feet (20 m) per side. In the center was a crypt believed to contain the remains of Philip. The building seems not to have been used as a church (no altar was found) nor as a burial site (no other tombs were found); it was probably set aside for processions and special services. Crosses and other Christian symbols can be seen carved over the arches.

To the west and south of the martyrium are the west necropolis and east necropolis, respectively. Another large necropolis is further to the north (see below). Also near here is a small early theater, of which little remains.

Northwest of the theater are the north Roman baths, built around the late 2nd century AD and used as a Christian basilica beginning in the 5th century.

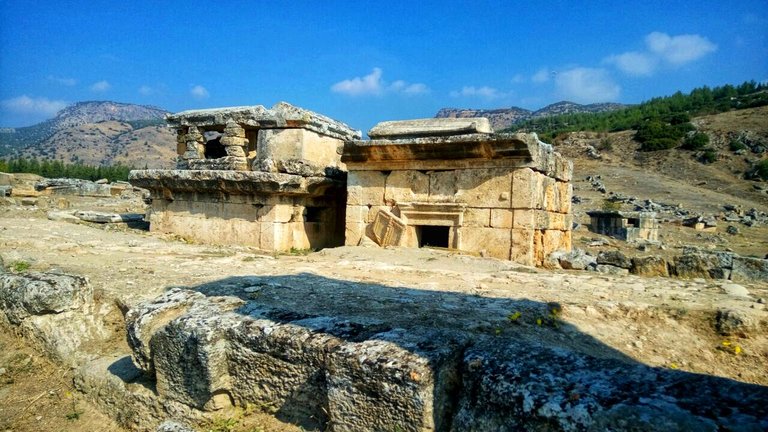

To the north of the main ruins and along the modern road is the north necropolis (graveyard), the largest in Anatolia. It contains more than 1,200 tombs of various types, including tumuli, sarcophagi and house-shaped tombs from the Hellenistic, Roman and early Christian periods. Some have Jewish inscriptions.

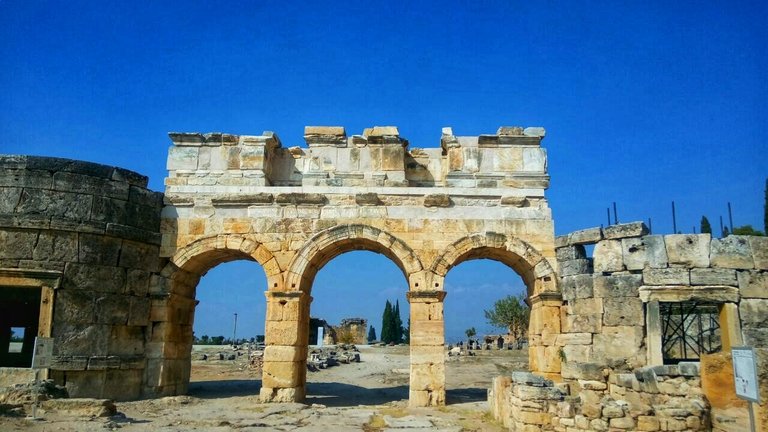

Nearby is the monumental Gate of Domitian (pictured at top), constructed around 83 AD to serve as the northern entrance to the city. It has three arches and two towers, and originally had two stories. The gate led into a colonnaded street known as Frontinus Street (named for its builder, the proconsul of Asia, who also built the Gate of Domitian). This was the heart of the city during Roman times, containing shops and public buildings under covered walkways.

On the left of the gate is a large latrine. To the right of the gate is the tomb of Flavius Zeuxis (pictured at top), notable because of its inscription proclaiming that the Hierapolis merchant had traveled to Italy 72 times by sea.

East of the main street is the huge agora, the largest uncovered one discovered in the ancient world. It is 580 feet wide and 920 feet long and was surrounded by Ionic columns. To the agora's east and up a flight of steps was a large stoa-basilica, 66 feet wide and 920 feet long. This was once richly decorated with popular ancient motifs including sphinxes, lions, bulls, garlands, Eros figures and Gorgon masks.

On the southwest side of the agora is a Byzantine Gate, part of the early 5th-century Byzantine wall that protected the city from invaders. Between the Byzantine Gate and the parking area, near the museum, are the remains of another 5th or 6th century Christian basilica.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://www.travelephesus.net/tour/daily-pamukkale-tour-2