No great battle ever took place here, nor are there any ancient monuments of wood or stone. The meadow looks like a thousand other Russian meadows, and yet, it is an unusual one.

A hundred years ago five boys spent the night here, sitting around a camp-fire while the horses they were guarding snorted in the dark, fish splashed in the river and a night bird called out shrilly. A hunter who had lost his way in the woods saw their fire and approached. He was the one to tell us of the night and the meadow, and of the boys' conversation. We all know their names: Fedya, Pavel, Ilya, Kostya and Vanya. Here are a few lines from that conversation: "There ought to be mermaids here..." "No... This is a clear, open place. There's one thing though: the river's near."

We have known about this night and these boys for a hundred years. We learned it would not be difficult at all to find the actual meadow. Driving around the coppices at the boundary of Tula Region, we finally stopped a man on the road who said: "Why, it's right there, beyond the field of rye."

It was just as Turgenev had described it: "It was a glorious July day, one of those days which come only after a long spell of fine weather." We parked the car on a rise, got out and nearly rolled down the steep, grassy side of the ravine. A herd of calves was grazing by some bushes. We asked the shepherd whether this was the meadow.

"Yes, this is Bezhin Meadow," he replied and stretched, for he had been dozing. "The village is called Bezhin Meadow, too."

We looked around. We were standing at the edge of a large green plain. The land with its ponds, orchards, ravines and strips of wheat and rye was now above us, dipping down rather sharply into the meadow on all sides, making the cool, damp plain resemble the bottom of a large bowl. Wild pear trees, oaks and elms grew in clusters and singly on the slopes.

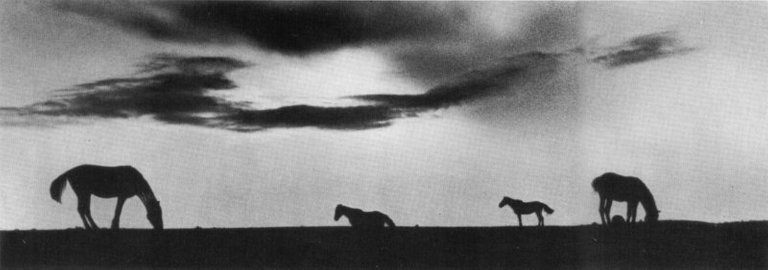

The meadow was dotted with willow thickets which appeared dark-green at close range and blue in the distance. At the edges, where the plain turned into knolls, everything was blue: the oaks on the rises, the curly bushes and even a horse and its colt. A sunny, golden mist permeated the blue, so that the horizon was all but obscured.

A large cloud, drifting from west to east, cast a cool shadow upon the plain. The meadow was more than large enough to mirror its every curl and wisp in the sparkling grass. We caught up with the edge of the shadow and accompanied it across the grass to where a strip of small willows and broom concealed the river.

We left a dark, damp trail behind as we walked through the yellow splashes of buttercups, the purple knobs of cornflowers, the bright and fragrant confusion of wild flowers and grasses.

We were on Bezhin Meadow. Bees buzzed and yellow wagtails perched on the stalks of wild sorrel following us with a wary eye. We startled a lapwing. Two landrails, one close by in the bushes, the other somewheres near the far knolls, were either calling to or trying to intimidate each other.

The only creature in sight was the blue horse in the distance. Was this how the meadow had looked a hundred years ago? Most probably. The knolls could not have changed, nor could the bushes or willows moved, and the river still followed its course. That was the rise from which Turgenev glimpsed the campfire. The boys were probably here by the bushes. We wandered through the grass, listening to the lapwing. There was a burned-out circle on the ground, left by another campfire, a scrap of cellophane and a box of matches. Some visitors had probably also sought out the spot and had made a campfire of their own. We regretted having to leave and being unable to spend the night here.

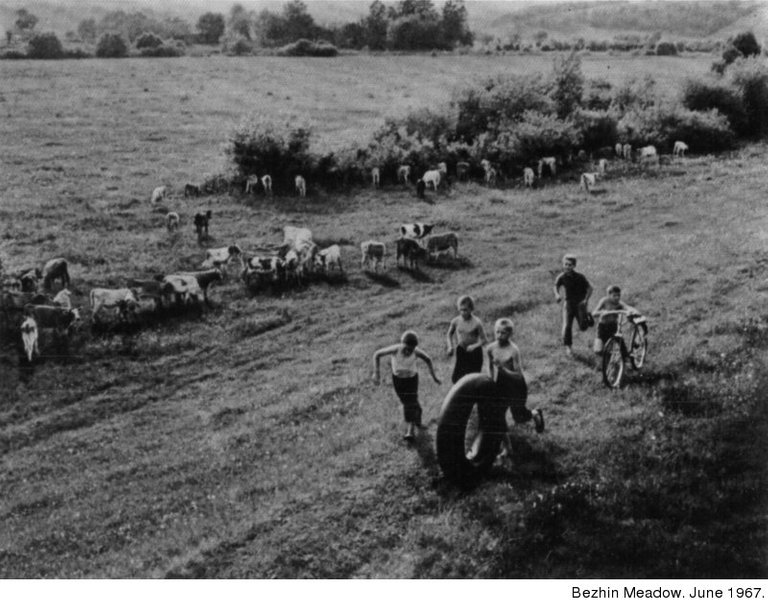

The horse was still grazing by the blue bushes in the distance. A tractor chugged beyond the meadow. There were several small houses and a cowshed where the old paper mill had once stood. I took some pictures, but felt that the main attraction was missing: there were no boys in them. And then suddenly (surely, a photographer's luck!) a group of boys came running down to the river. They were skipping and racing as they rolled along the inner tube of a truck.

Ten minutes later we knew that the river was the Snezhed River, that Bezhin Meadow Village was a kilometer away, that a late frost had nipped the potato and tomato plants, that they all tuned in Moscow on their TV sets, that four of them knew how to ride and that the fathers of two were truck drivers who sometimes let their sons sit in the driver's seat.

"We heard there were mermaids and witches here," we said.

The boys exchanged glances and snickered.

As I jotted down their names I asked them whether they knew any local boys named Fedya, Pavel, Kostya and Ilya.

"Who are they?" the eldest boy asked warily. "Ah, I know! That's from Bezhin Meadow, isn't it?"

Then the others chimed in.

The boys asked whether they might borrow our automobile pump to blow up their inner tube. They huffed mightily as they took turns pumping, kicking the tube with their bare feet to test it. Then we watched their blond heads darting in and out of the bushes and heard the loud slaps of their hands on the tube.

The boys Turgenev had written about had grown up, had had children and grandchildren. These boys would have been their great-grandchildren... But the meadow was unchanged.

Vapors were rising from the vast expanse of grass as the day drew to a close. The landrails were still calling shrilly, and the calves grazed lazily. The meadow was as young as ever.

We could still hear the landrail below us as we drove off.

Love the style and description of nature in all her glory.

This story packs a punch of yearning memories that whisk you away to a special place we can all relate to. Thank you!